Blaming workers receiving higher pay for inflation is wrong, and shows a lack of understanding around the primary mechanism in which price rises eventuate. Instead of driving today’s high inflation, workers are suffering from it, desperately trying to keep their heads above water, as the waves grow higher, and the current gets more vicious. This can clearly be seen in the actual data, with total compensation significantly lagging the increase in inflation as measured by the CPI (Figure 1).

Instead of wages driving inflation higher, the same thing that has driven inflation higher, is driving wages higher.

It all boils down to the extreme post-COVID increase in the money supply

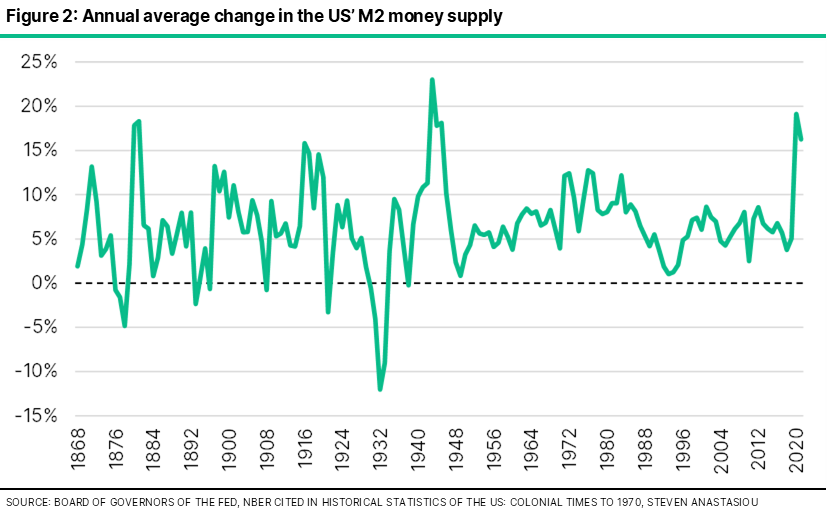

That thing has been the extreme surge in the money supply that occurred in response to COVID-19 (COVID). Just how extreme? In the US, the annual average increase in the money supply in 2020 was the second highest in its post-Civil War history! This was followed up by another extreme rise in 2021 (Figure 2).

This, and not the hard-working middle-class men and women, simply striving to put food on the table for themselves and their families, and who simply request that their pay move up alongside the increase in their cost of living (even though most don’t receive pay rises that fully compensate them), is what drove today’s high inflation.

How did it do that? The explanation is quite simple, and would seem like common sense to most - perhaps that is why it is far too often ignored by policymakers, who with their PhDs and increasingly ludicrous and nonsensical mathematical models, get too clouded in the noise, and who insist it is much more complicated, and too difficult for simple common folk to comprehend.

There are two different ways in which one can think about the impact of an increase in the money supply on prices. The first is the demand side impact, which is more readily understood, and the second is the psychological impact, which is less commonly considered, but also of significant importance.

When more money is printed, there is now more money available to chase a given good or service

Dealing with the demand side first, when more money is printed, there is now more money available to chase a given good or service. In isolation, this increase in demand will raise prices. Taking the US as an example, it had a broad (M2) money supply of $15.4tn at the end of 2019. By the end of 2020 this increased to $19.2tn, and rose to $21.7tn by the end of 2021 – an increase of 40.5 per cent from the end of 2019. 2020 and 2021 thus saw relatively sudden and huge influxes of new money pushed into the economy. What do people do with money? They buy stuff. A huge 40 per cent increase meant that people on average now had a LOT more money to spend! Given that the supply of goods and services could not increase by such a large amount in such a short space of time, there were more dollars chasing a given good or service, causing prices to rise and shortages to ensue.

This is a fundamental truth of economics, being that when demand increases at a faster rate than the increase in supply, prices will rise. Just as this is true for an individual good like apples, it is true for the economy as a whole. The primary driver of a broad economy-wide increase in demand (the kind needed to impact inflation), is a change in the money supply – the more money that exists, the more money that can be thrown at goods, services and assets. Rather than being rocket science, this is just common sense.

The psychological driver behind an increase in the money supply & prices

The second money supply driven driver of inflation is the psychological component. This component is less well understood, but also very important. Think of this firstly at the individual level - think of yourself. If today you have $10,000 in your bank account, but tomorrow you win the lottery, and your bank account grows to $1m, either consciously or unconsciously, you will now value a given unit of currency at a lower amount than you did before you had won the lottery.

Whether or not the actual quantity of goods and services you consume changes very much isn’t the key point here. Indeed, let’s say that you are a very frugal person. You may also be somebody who cares deeply about the environment, and the impact that excessive consumption can have on it. You may also be somebody who does not buy into the consumerist narrative of increasingly accumulating more material possessions. All of these things may mean that your demand for goods and services wouldn’t change very much. Nevertheless, the psychological value you apply to a given dollar, will now still very likely be lower.

When you have only $10,000 in your bank account, you might second guess whether or not you should walk the extra half-mile to save $2 on your coffee, or $3 on your avocado and toast - but with $1m in your bank account, you suddenly become far less likely to take that extra half-mile walk, as after all, with $1m in the bank, what is an extra dollar or two going to do? The time and effort involved in saving a dollar suddenly becomes a whole lot less important when your bank account has six zeros instead of four. Whether you have consciously realised it or not, your perception of the value of money has changed.

Again, this is a fundamental truth - when something suddenly increases in abundance, in isolation, each unit of that thing will now be worth somewhat less than it was before. Just how much less each unit will be worth to a given person will be unique to each individual, but the fundamental truth that it will be worth less, will nevertheless remain true.

As individuals attribute a lower value to a specific unit of money, goods and services priced in it will end up costing more, as individuals are now more likely to exchange it for goods and services at a given price than they did previously.

An increase in the money supply thus creates inflation by 1) raising the actual demand for goods and services and 2) reducing the psychological value that one applies to a given unit of currency.

But what about the supply-side of the equation?

While it is true that inflation is also impacted by supply-side factors (being factors that impact the total supply, and productivity of, the factors of production), the supply-side generally acts to REDUCE inflation over most time periods, as best evidenced by 1) ongoing productivity growth, and 2) globalisation and technology benefits leading to lower tradables and goods inflation (versus non-tradables and services).

While many will be jumping up-and-down saying that COVID impacted the supply-side and THIS is what caused the current high inflation, this is simply not true.

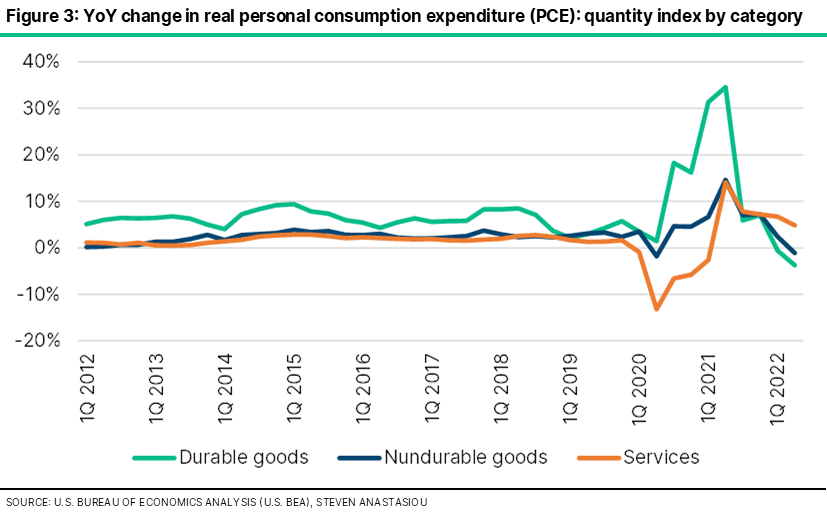

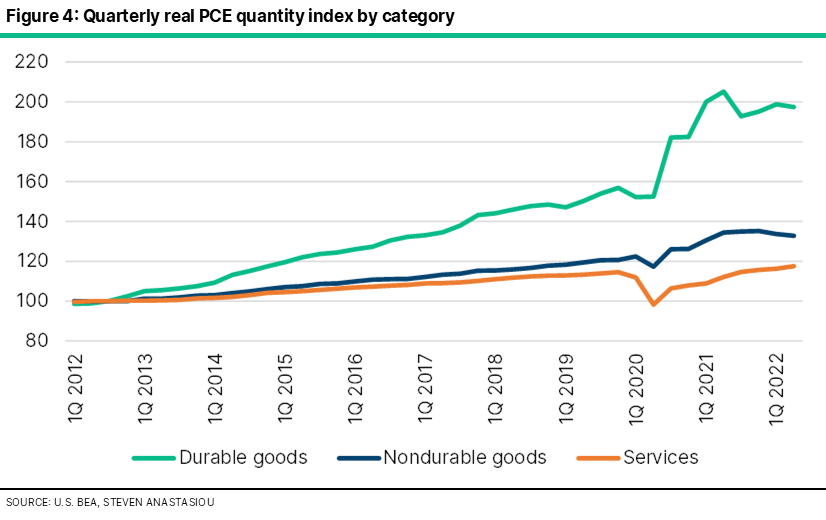

Inflation did not rise materially until Q2 2021 – over a full-year after COVID lockdowns initially occurred. What caused inflation to spike at this point in time? The surge in durable goods demand that came alongside the March 2021 passage of the American Rescue Plan (ARP) (i.e. alongside another large increase in the money supply) (Figures 3 and 4).

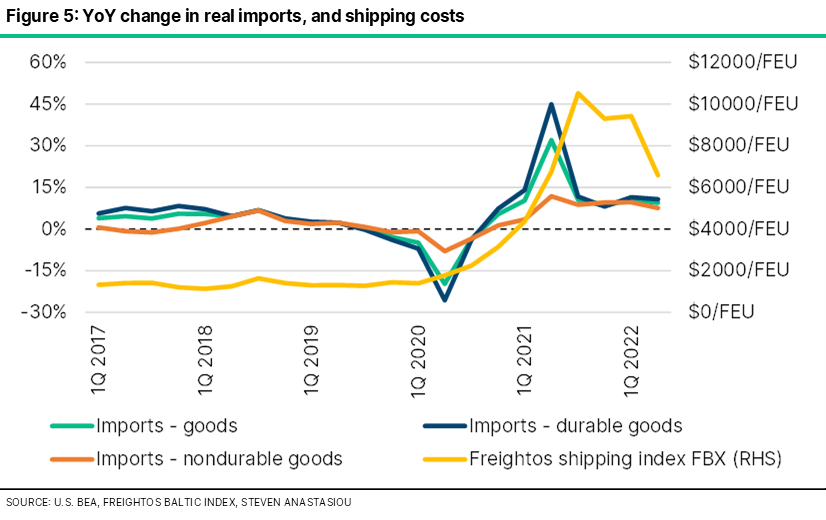

Alongside this spike in demand came the infamous surge in shipping costs (Figure 5) as global supply chains struggled to cope with the sudden additional influx of demand. This was not just COVID related as real durable goods demand was ~30 per cent ABOVE its pre-COVID level at this point – supply responded, it just couldn’t keep up with the enormous surge that the extreme increase in the money supply created. COVID or no COVID, no economy could have handled such a sudden surge in demand without price rises and shortages.

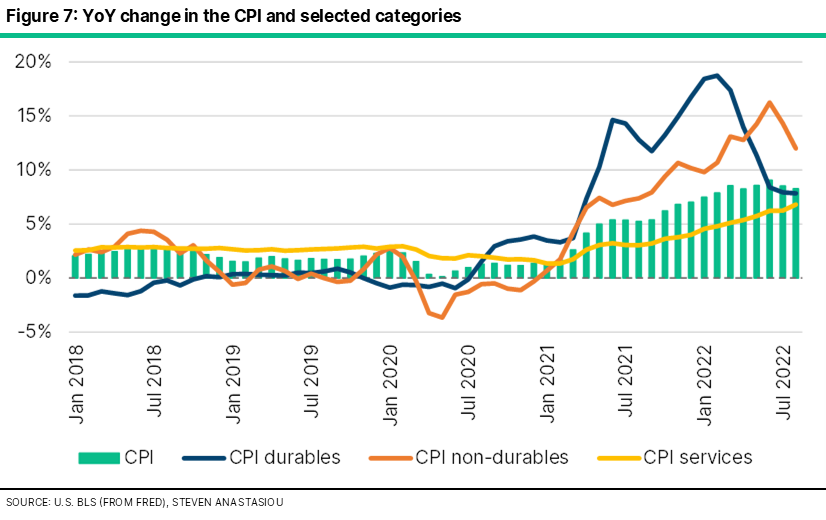

After durables prices surged on the back of the Q2 2021 surge in demand (Figure 6), price rises later filtered throughout the economy as the increased money supply continued to spread throughout it (Figure 7). As they say, the rest is history.

Just as workers didn’t cause today’s high inflation, it won’t spiral if they continue to receive pay rises

Those harping on about wages, including many central banks, suggest that even if they were not the cause of the current high inflation, if current wage increases are not shot down, people's incomes will rise, creating an increase in business costs and consumer demand, which will lead to further increases in inflation, which in-turn drives a further increase in wages, and which could continue in a positive feedback loop into perpetuity if central banks do not act to stop it.

While such a theory may seem to have merit on the surface, a deeper analysis reveals it is either little more than central bank scapegoating away from their own policy failures, or another example of how they so badly fail to understand the real driver of high inflation, being an artificial increase in the money supply. Remarks from central bank chiefs making ~US$650,000 per annum, that hard working individuals are somehow responsible for inflation becoming engrained if they receive large pay rises, and that they should thus forgo asking for such rises, is an unjustified and undignified attack on workers. Instead, one needs to understand that 1) wage setting is largely a function of the free market, and 2) even if wages were arbitrarily set, its primary consequence in a globalised world would be unemployment and economic decline, not inflation.

Just like other prices in the economy, wages are set by the market

It is vital to recognise that today, the great bulk of workers do not belong to a union, with only 10.3 per cent of US workers having a union membership in 2021, meaning that most workers are incapable of organising mass picketing and strikes to demand higher wages. This means that as opposed to some evil intent on the part of workers to destabilise the economy and put their self-interest above the greater good, current wage growth is being driven by market forces. Just as other prices are rising as demand outpaces supply, businesses are increasing their demand for workers at a faster rate than the increase in their supply, resulting in wage rates being bid up. Just as it is not evil for a business to increase its prices in response to higher demand for their service, it is not evil for a worker to receive a higher wage for their time and effort, in response to their skills being in higher demand. This is how free markets work. Those wanting to put a stop to wage rises must either be inherently anti-free markets, anti-working class, and/or ignorant of economic reality.

Even if wages were arbitrarily set, it would primarily create unemployment and economic declines

But for arguments sake, let us assume that workers increasingly formed unions and collective bargaining in response to rising inflation, or that the limited sectors that remain unionised received large increases in pay so that non-unionised employers had to compete with those higher wages to retain and hire the necessary staff that they need. What would happen then? Surely this would create a wage-price inflation spiral as a primary consequence? It’s just common sense, isn’t it? Again, the answer is no.

In the absence of an increase in the money supply, even if workers got an increase in wages, the aggregate level of money held in the economy is unchanged. All that has happened, is that workers now receive a greater share of the economic pie than owners/shareholders of capital. Given that the aggregate money supply hasn’t changed, there would be a limited impact on aggregate demand, limiting the ability for the demand-side to drive inflation higher.

Instead, wage rises above levels that are demanded by the market would create another problem — unemployment. If individuals are somehow able to continually receive wage rises over and above market levels, business profitability would deteriorate, and thus their demand for labour would decline. Domestic production would suffer, and goods would increasingly be sourced from more efficient overseas producers (sound familiar?).

While there would be some real price pressures in services industries where imports are often not possible, the decline in the economy’s overall competitiveness and productive capacity would reduce real wealth, meaning that price pressures will likely be partly offset by the decline in supply being partly offset by a fall in demand. It is also important to remember that wages only form part of the overall cost of production - even for services based businesses.

Ultimately, just as printing money does not create wealth, but creates inflation, artificially raising wage rates may be beneficial for those who retain a job, but it too has real costs. Though as opposed to the primary cost being inflation, the primary cost to artificially raising wage rates will instead be that overall employment will be lower than otherwise and the competitiveness of the domestic economy will decline versus the global economy. While this could have major consequences if taken to extreme levels, including a significant deterioration in the value of the currency, which would reduce the ability of imports to offset higher domestic costs and thus create inflationary pressure, its primary consequence remains unemployment. This differs to an increase in the money supply, which has inflation as its primary consequence.

Nevertheless, this scenario is NOT what is happening in most economies worldwide today, whereby wages are instead simply playing catch-up to rising prices, and are responding to market-based forces, as the surge in the money supply and the associated increase in demand for goods and services that this created, is resulting in additional demand for labour, which is pushing up its market price.

Why then is there such a focus on wages – scapegoating or just more ineptness?

If wage rises are not the cause of inflation, why do they form such a significant point of focus for central banks? Do they simply seek to permanently de facto enslave a large undercurrent of the population, as a great deal of cynics would suggest? I don’t believe it’s quite that bad. Instead, I believe a more plausible explanation would likely lie in a very powerful explanatory variable – being that of self-interest. If one seeks to find the truth, I believe answering this question will often reveal where it lies.

For a central bank it is certainly in their self-interest to explain high inflation, a terrible disease for which they are responsible in preventing, on something other than their own policy failures. In that respect, it thus makes sense to deflect away from their hopelessly inept policymaking, and instead blame rising wages.

But even this theory I don’t fully buy. Instead, I believe (perhaps in somewhat naive hope), that as opposed to a nefarious intent, it instead largely boils down to the fact that central bankers astoundingly have no real comprehension as to how inflation is actually created — that being an increase in the money supply. Instead of actively following this metric, and despite the overwhelming historical evidence that this is the key driver of inflation, the Fed, and most central banks, in their infinite wisdom, have in more recent times decided to analyse just about every other explanation for inflation, EXCEPT the money supply.

By doing so, they have misplaced the real driver of inflation with other erroneous theories, including that of the wage-price spiral. Why have they done so? I believe it is because 1) artificial increases in the money supply impact inflation with a lag, and 2) during times of moderate money supply growth, general improvements in supply-side conditions suggest that the money supply doesn’t have a strong correlation to inflation. As a result, they have incorrectly disputed the role of the money supply in creating high inflation. I have written more about this in my previously released 70-page report on inflation, which is available here.

Ultimately, whatever the reason for central banks targeting wage growth, it needs to be pushed back upon. Not only is it plain wrong, but it’s a policy that if successful, essentially further entrenches relative poverty and inequality. Obviously, this should seem like a counterproductive idea. For what good is reducing inflation if it can only be achieved by reducing workers wages? How then, can workers be better off? Instead, we need to tear down at such fallacies, and continue to spread the truth behind the real driver of high inflation, being reckless government deficits and central bank policies, which result in artificial increases to the money supply. This, and not workers trying to keep their heads above water, is where the real reason for today’s high inflation lies.