When will the Fed deliver the first rate cut?

Despite Fed assurances that rate cuts aren't on the horizon, with real rates likely to soon hit significant levels, the jobs market is likely to decide whether rates are cut in 2H23.

While the Fed continues to postulate that it doesn’t see any rate cuts during 2023, with the CPI likely to see major disinflation over the next two months (I currently forecast a decline to 3.1% in June), and employment growth weakening, there’s plenty of historical evidence to suggest that rate cuts may not be too far away.

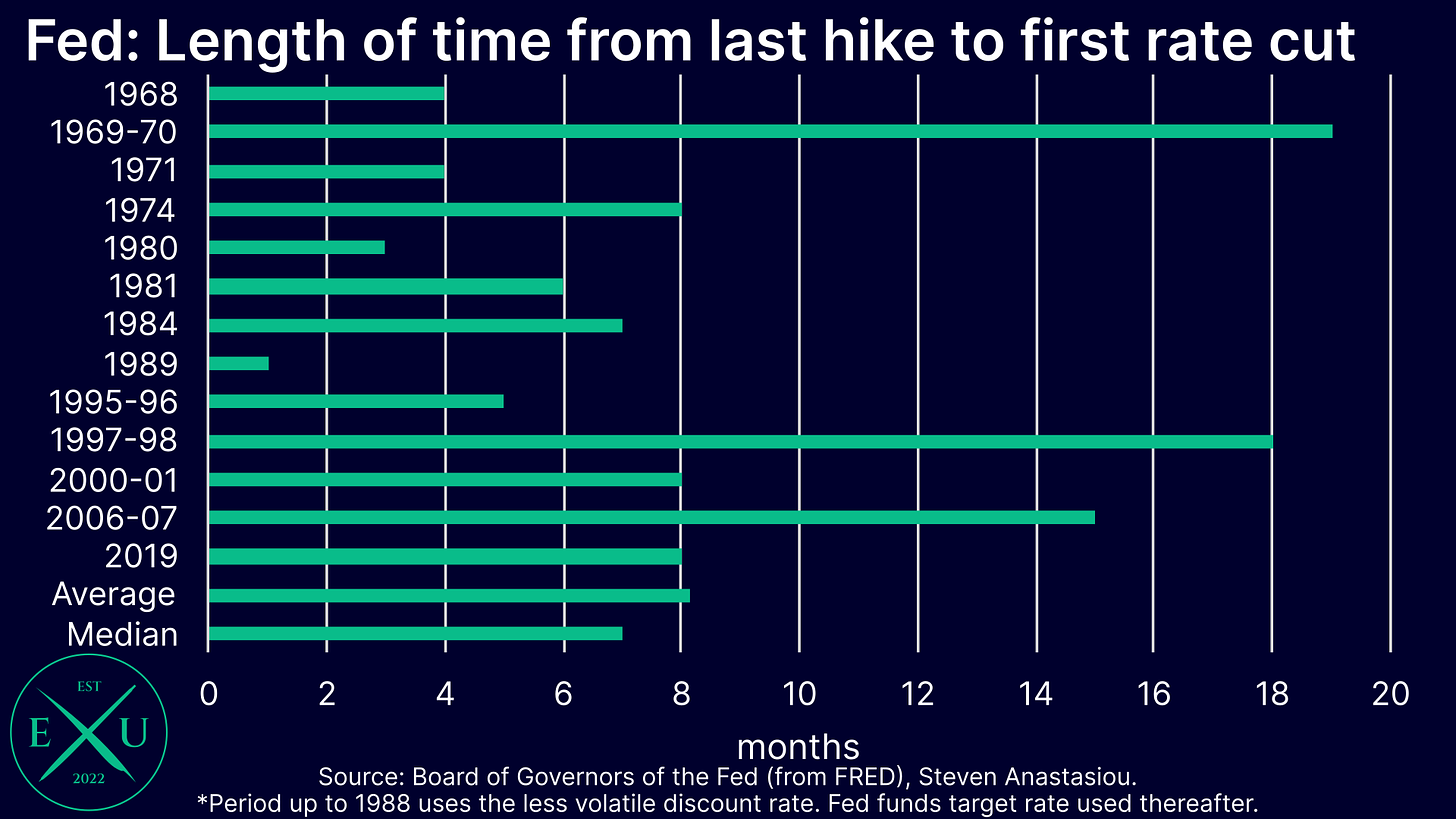

Last rate hike to first cut: 7 months is the median length of time

In data dating back to 1968, the median length of time that passes from the Fed’s last rate hike to its first rate cut, is 7 months. This analysis uses the Fed’s less volatile discount rate up until 1988, and the Fed’s federal funds rate target thereafter.

The longest stretch of time between the last rate hike, and the first rate cut of the cycle, is the 19 months spanning across 1969-70, that it took for the Fed to lower its discount rate. On the flipside, the shortest was just one month, when the federal funds rate target was cut in June 1989, after being raised in May.

Should May’s interest rate increase be the last of the current hiking cycle, 7 months to the next rate cut would result in the Fed cutting rates at its December meeting.

Note that during Volcker’s tenure, and at times when high inflation was a major concern, the discount rate was cut in 1980 and 1981, just 3 and 6 months after the last increase in the discount rate, respectively.

Real rates set to rise significantly from June — will they be high enough to warrant rate cuts?

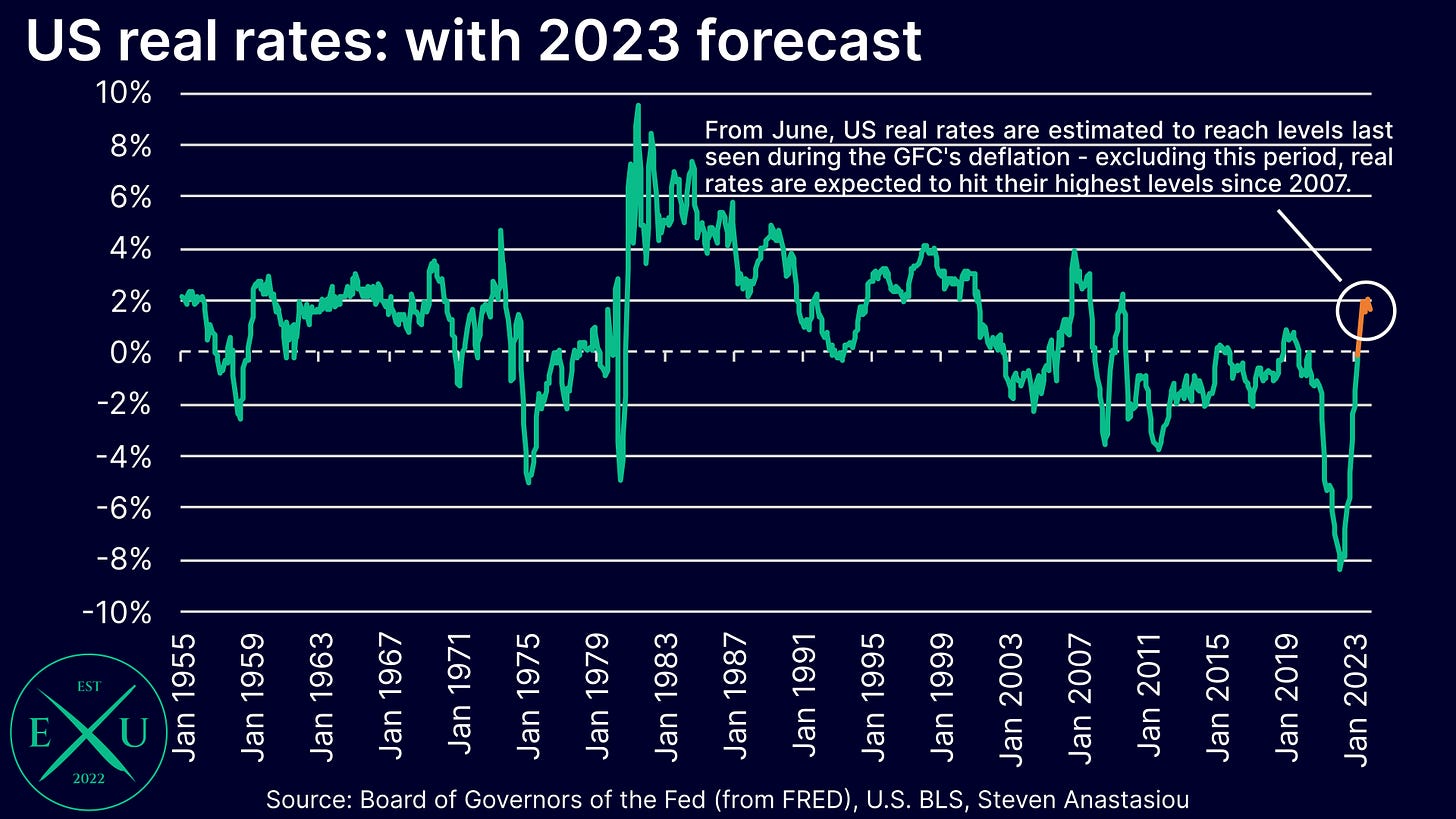

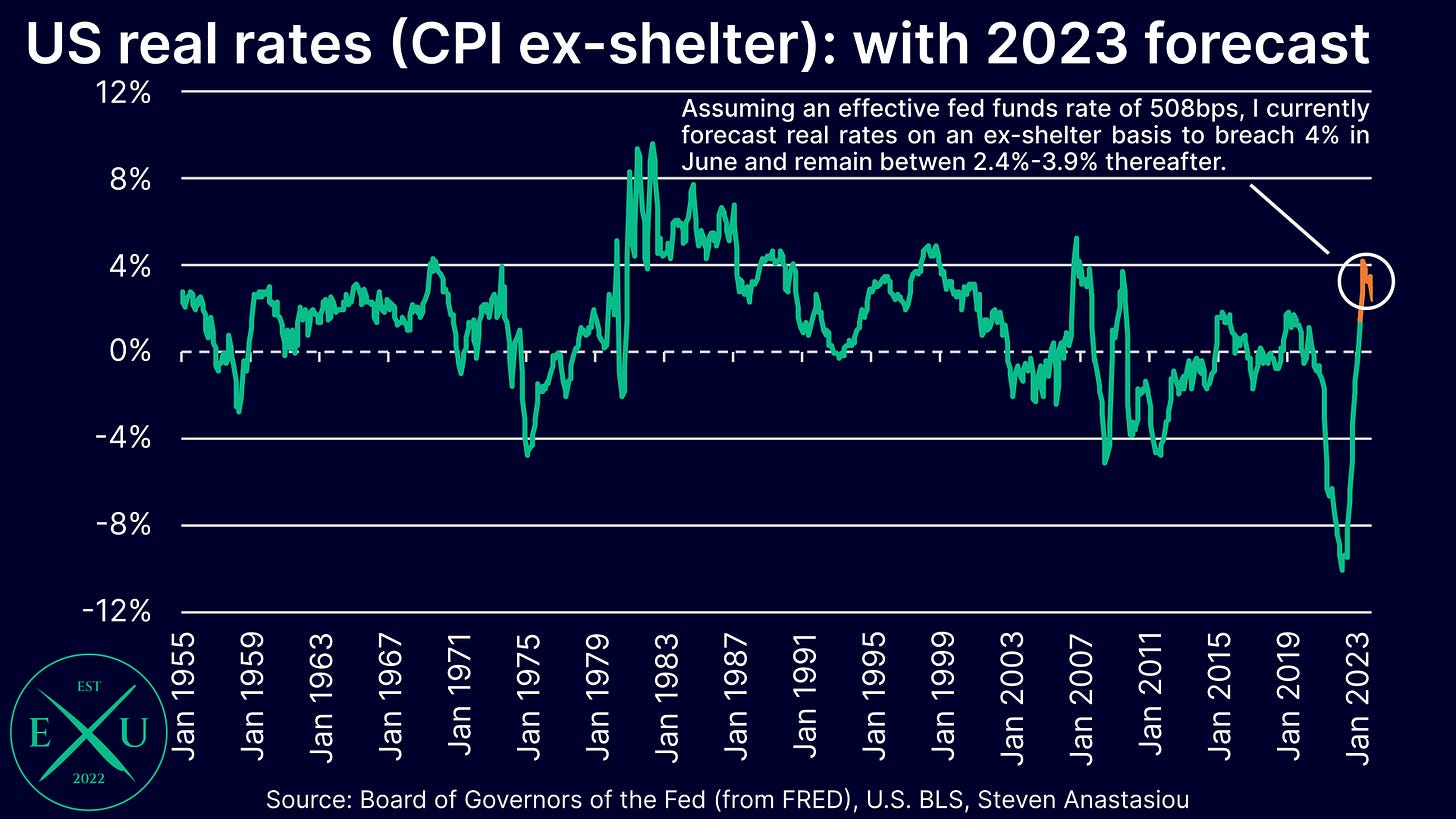

Given my expectation for a major decline in the rate of CPI inflation over the next two months, I expect the real interest rate (defined here as the actual/forecast effective federal funds rate less the actual/forecast annual rate of CPI inflation in the given month) to hit 2% in June. This is based on the federal funds rate remaining at its current effective level of 508bps, and my most recently released 2023 inflation forecast.

This is significantly higher than the historical average real interest rate of 1.0%, dating back to 1955.

Since 1955, the real rate has fluctuated widely. There was a long stretch of generally positive real interest rates from ~1959-1973, with real rates turning largely negative (often sharply) across ~1974-1980, as inflation rose.

Volcker’s aggressive rate tightening led to a reversal of significantly negative real interest rates, to majorly positive real rates, which peaked at 9.5% in June 1981.

This began a new period of generally significantly positive real interest rates, which lasted until the Fed’s aggressive interest rate cuts in 2001. These cuts led to another period of significantly negative real interest rates, which sharply pushed up debt levels and the US housing market.

After real rates returned to positive territory in late 2005 as the Fed increased the fed funds rate, the GFC ushered in a new period of generally negative real rates.

Assuming that the Fed holds rates at 500-525bps (resulting in the federal funds rate continuing to remain at an effective level of 508bps), and excluding the brief deflationary period of the GFC, by June, I forecast that real rates are likely to return to their highest levels seen since 2007.

While positive real rates are part of the Fed’s plan to rein in inflation, the key question is, at what point may they reach a significantly restrictive level that rate cuts could be warranted?

On this point, many would look at the extremely positive real rates under Volcker’s inflation fight and say that the Fed isn’t doing anywhere near enough. I would disagree with this point of view for three key reasons:

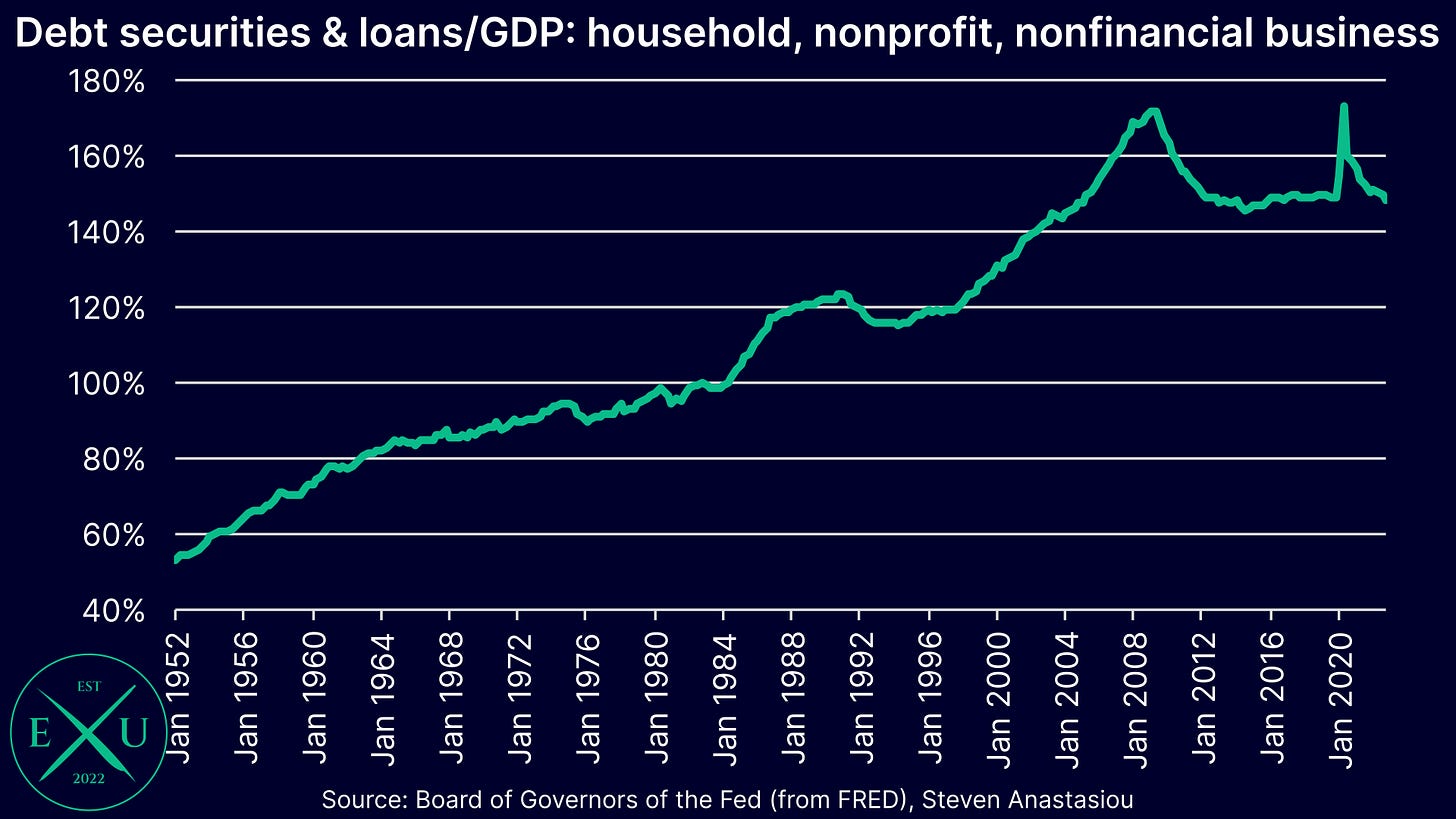

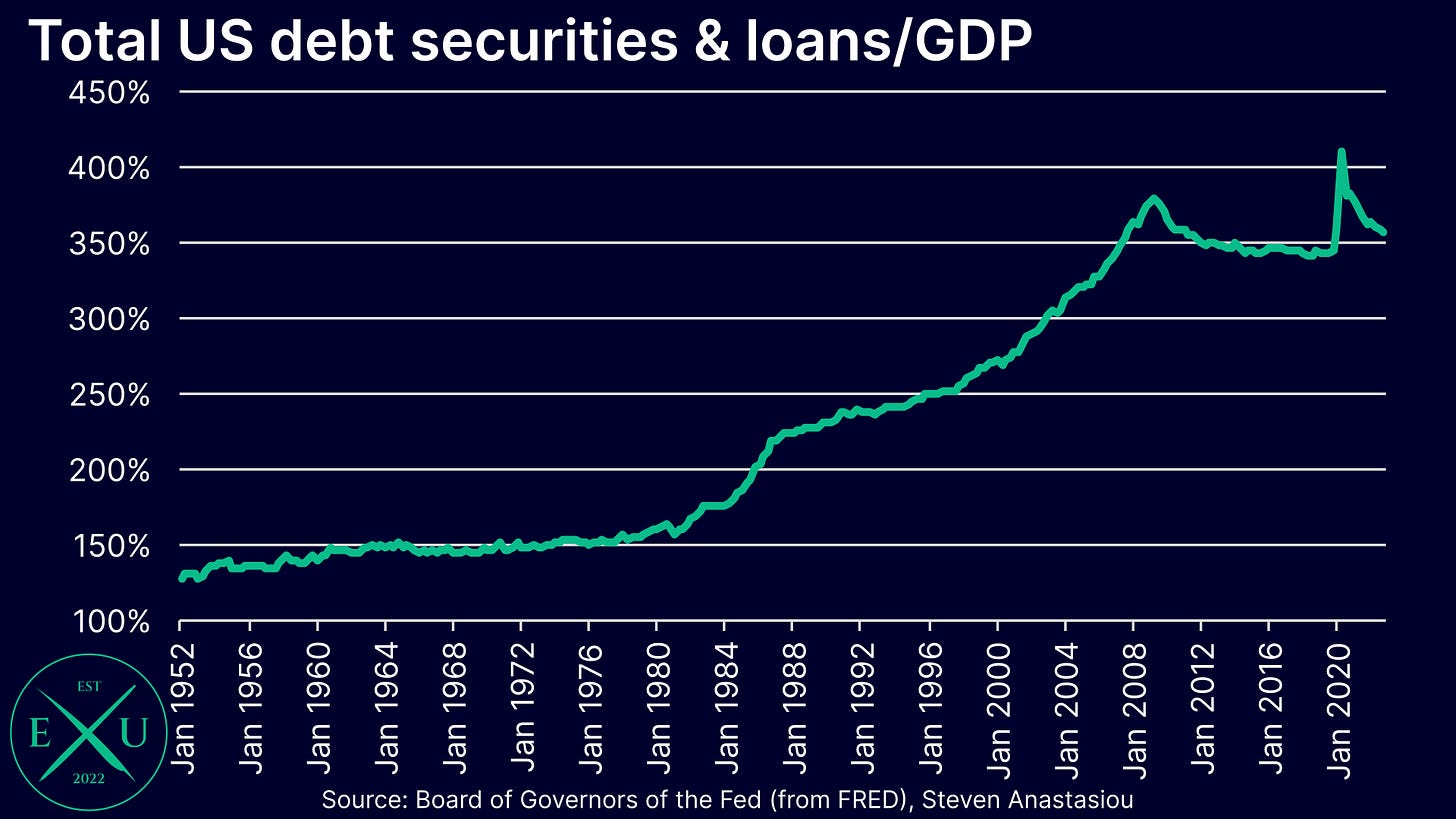

Debt levels are far higher today than they were in the 1980s, meaning that interest rate increases have a greater impact on the economy today. Just how much higher are debt levels today? Household, nonprofit organisation and nonfinancial business debts were equal to 148.6% of GDP in Q4 2022, up from 97.6% in Q1 1980.

Once government and all other debts are added into the equation, total US debt to GDP has risen from 160.9% of GDP in Q1 1980, to 357.7% of GDP in Q4 2022.

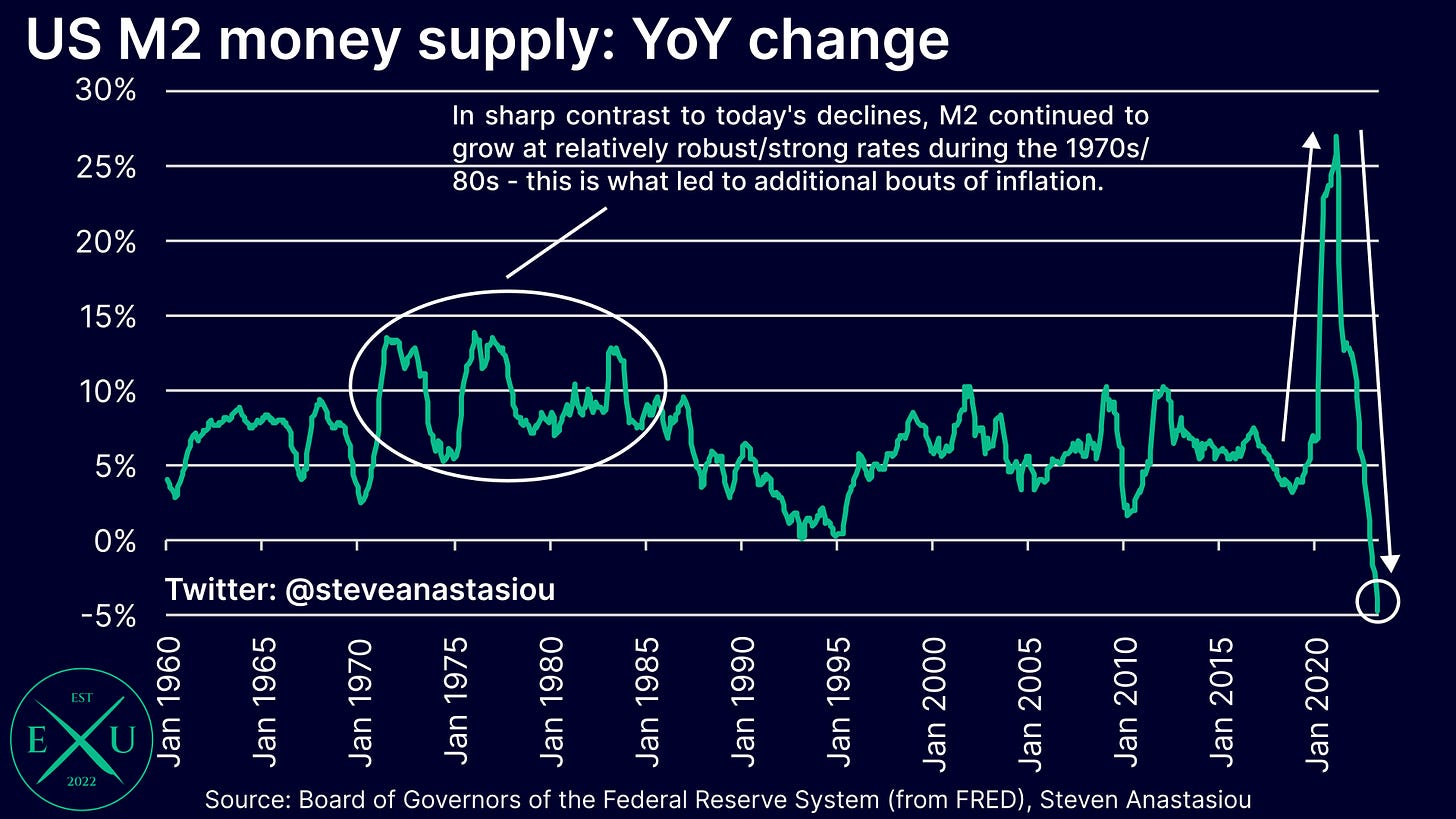

With aggressive rate rises being combined with QT, the Fed has much more effectively (despite not specifically having it as a target) contained growth in the M2 money supply versus the 1970s/1980s.

M2 is now seeing its largest annual declines since the Great Depression, whereas M2 continued to record generally robust growth rates during the 1970s/1980s.

There is thus no monetary impetus for another bout of high inflation, in stark contrast to the 1970s/80s.The CPI is currently being artificially elevated by the lagging measurement of rents — on an ex-shelter basis, I currently expect real rates to breach 4% in June, and remain between 2.4%-3.9% thereafter, which is well above the historical average of 1.2% dating back to 1955.

In terms of Fed Chair Powell’s comments on the subject of real rates, in his most recent May FOMC press conference, Powell noted that he thinks “policy is tight”, and that with rates at ~5% and “a reasonable estimate of … 1-year inflation, which might be 3% … you’ve got 2% real rates. That’s meaningfully above what most people would … assess as … the neutral rate. So policy is tight.” The historical record as discussed above, supports Powell’s assessment.

Though remember, as opposed to being here in a year’s time, ~3% CPI inflation could be less than two months away, which is likely to further reinforce the tightness of current policy settings. With further tightening not being needed to reduce money supply growth (which is already negative), should the economy weaken significantly in 2H23, the prospect of significantly positive real rates (and particularly so on an ex-lagging shelter basis), leaves the door open for rates to be cut in 2H23.

Jobs the key swing factor: falling employment growth coincides with peak rates & once it turns negative, big cuts come quickly

The aforementioned point about a weakening economy, is likely to prove critically important for the future rate outlook.

In illustrating this point, see the following exchange in Powell’s May FOMC press conference:

EDWARD LAWRENCE (Fox Business): How does the other side of the mandate—the jobs side—once you get to 3 percent, going from 3 to 2, how does the other side of the mandate balance?

CHAIR POWELL: I think they, they—you know, they, they will both matter equally at that point.

As opposed to having a practical sole focus on inflation at present, once inflation returns to 3%, Powell has thus indicated that the Fed will then adopt a more nuanced approach, seeking to balance both inflation, and the employment side of its mandate.

Remember, I currently forecast CPI inflation to range between 3.1%-3.5% from June-December 2022. A more nuanced approach to the Fed’s policy decisions, thus may not be too far away.

With an expected decline in CPI inflation pointing to significantly positive real rates in 2H23, the key swing factor for the future rate outlook, is likely to be the jobs market.

Should unemployment remain low, there will be far less impetus for the Fed to move rates lower. Though should employment growth continue to slow, and unemployment rates rise, the impetus to cut rates is likely to increase dramatically.

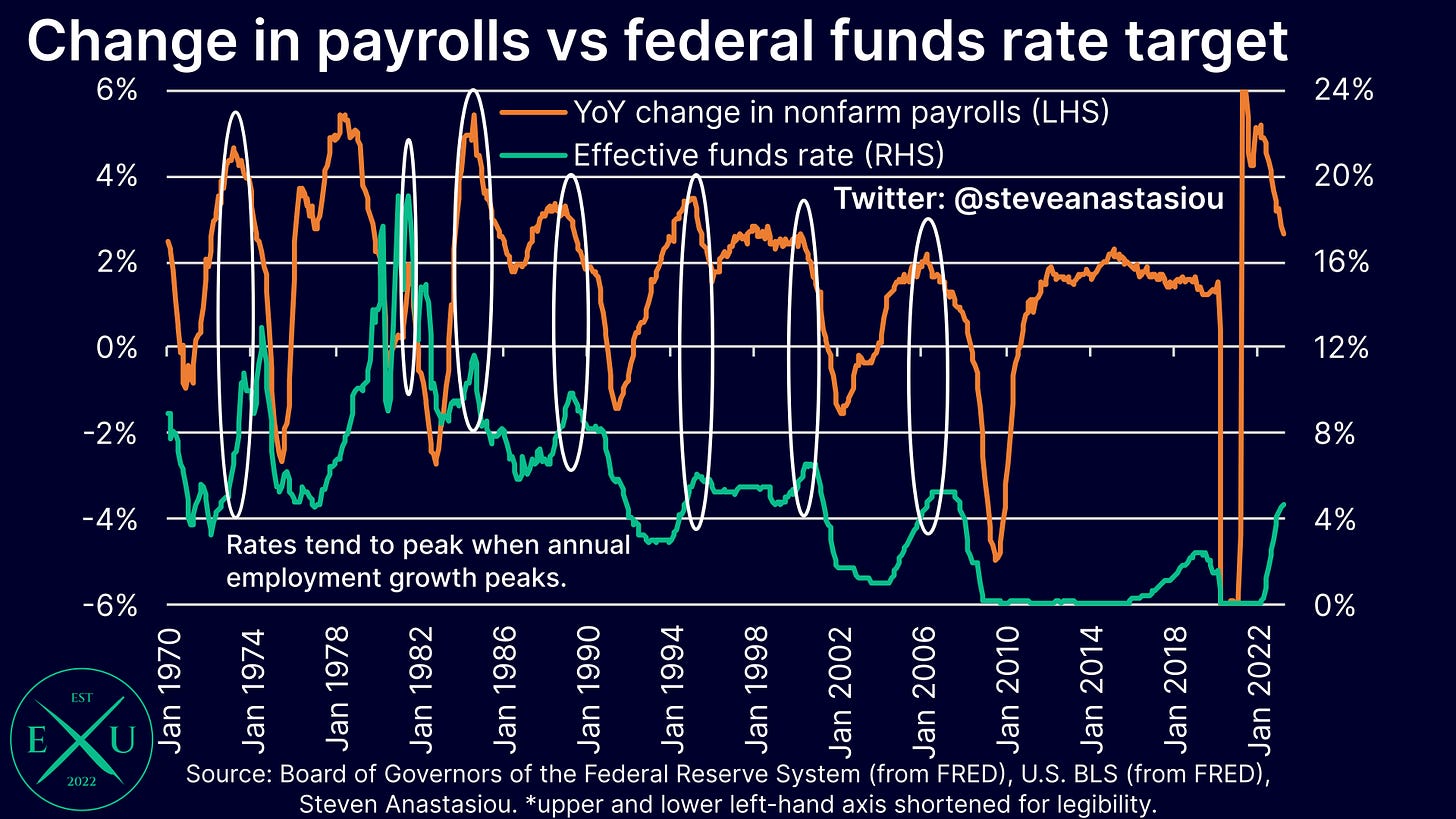

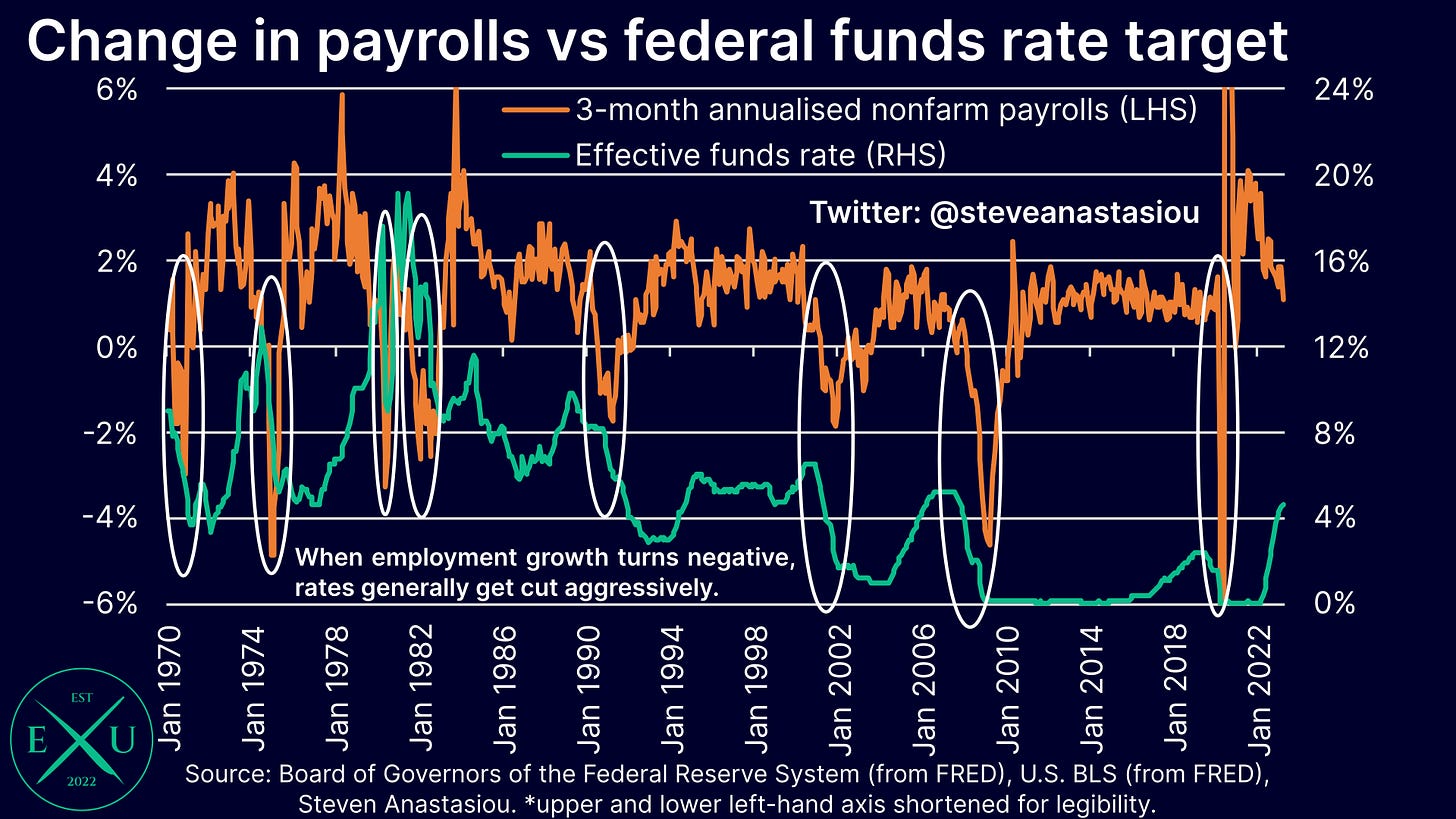

This is consistent with what has been seen from the Fed in prior business cycles, with rates generally peaking when annual employment growth peaks, which is illustrated in the chart below.

Looking at things on an annualised 3-month moving average basis, shows that once employment growth turns negative, rates tend to be slashed aggressively — note that this includes the high inflationary periods of the 1970s/80s, including under Volcker’s tenure as Fed Chair.

On both a YoY, and 3-month moving average basis, we can see that employment growth has today slowed significantly. With this slowdown coming from historically elevated levels, current growth rates are now in-line with historical norms.

Should employment growth continue to moderate significantly (of which leading cyclical indicators of manufacturing and temporary help services employment point to economic weakness lying ahead), current consensus views around the health of the employment market could shift dramatically in 2H23.

History says that if a significant weakening in the employment market does occur, and particularly if some months see employment declines, rate cuts are likely. The potential for rate cuts under such a scenario is likely to be enhanced by the prospect of real rates turning significantly positive over the months ahead.

What about the Fed’s current language? Remember what the Fed said in December 2021

With historical precedent and key indicators pointing to the potential for rates to be cut in 2H23, and particularly so should employment growth weaken significantly, what are we to make of the Fed’s current commentary that continues to insist that rate cuts are not on the way any time soon?

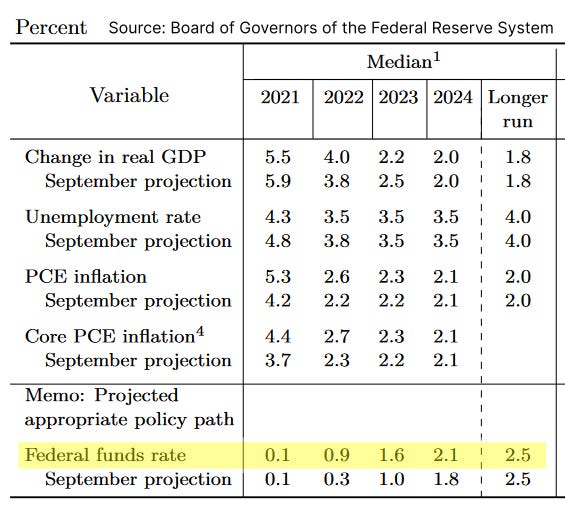

Remember what the Fed said back in its December 2021 economic projections — they expected the federal funds rate to end 2022 at 0.9% and end 2023 at 1.6%.

After watching CPI inflation hit 7.9% in February 2022, the Fed delivered its first rate hike of the current cycle and ended QE in March 2022. We all know about the abrupt shift in policy that happened after that point, with rates ultimately ending 2022 at a target range of 425-450bps.

Remember also, what happened to rates under Volcker’s tenure when unemployment rose and recessions abounded — they went down significantly.

In summary

History shows that a rate cut late in 2H23, would be far from unusual, with the median length of time between the last rate hike, and the first rate cut, being a period of 7 months in data dating back to 1968. During periods of higher CPI inflation than today, Volcker cut the discount rate 3 and 6 months after the last hike, in 1980 and 1981 respectively.

With significant CPI disinflation likely imminent, real rates are set to become significantly positive by June.

Given this backdrop, the key factor that is likely to determine whether or not the Fed will cut rates in 2H23, is the employment market.

Should the jobs market weaken significantly in 2H23, external pressure on the Fed to cut rates is likely to reach fever pitch: irrespective of what the Fed is saying today, history suggests that should such a scenario play out, rate cuts would follow.

Thank you for reading! I hope you enjoyed my latest research piece.

In order to help support my independent economics research, please consider liking and sharing this post. Given that Economics Uncovered is very much an independent endeavour, your support in sharing the word provides a great help in allowing me to continue to provide you with independent, institutional grade research.

Please feel free to leave any comments below, to which I will endeavour to respond.

If you haven’t already subscribed to Economics Uncovered, subscribe below so that you don’t miss an update.

Great insight!