US jobs report: May 2023 review

The same story: a weakening trend, but the overall picture still remains relatively solid.

While the US jobs market continues to be in a weakening trend, May’s BLS employment data continues to show an employment market that remains relatively robust — further time will be needed for the US jobs market to weaken to a level that would see the Fed materially adjust its monetary policy stance.

Let’s unpack the details.

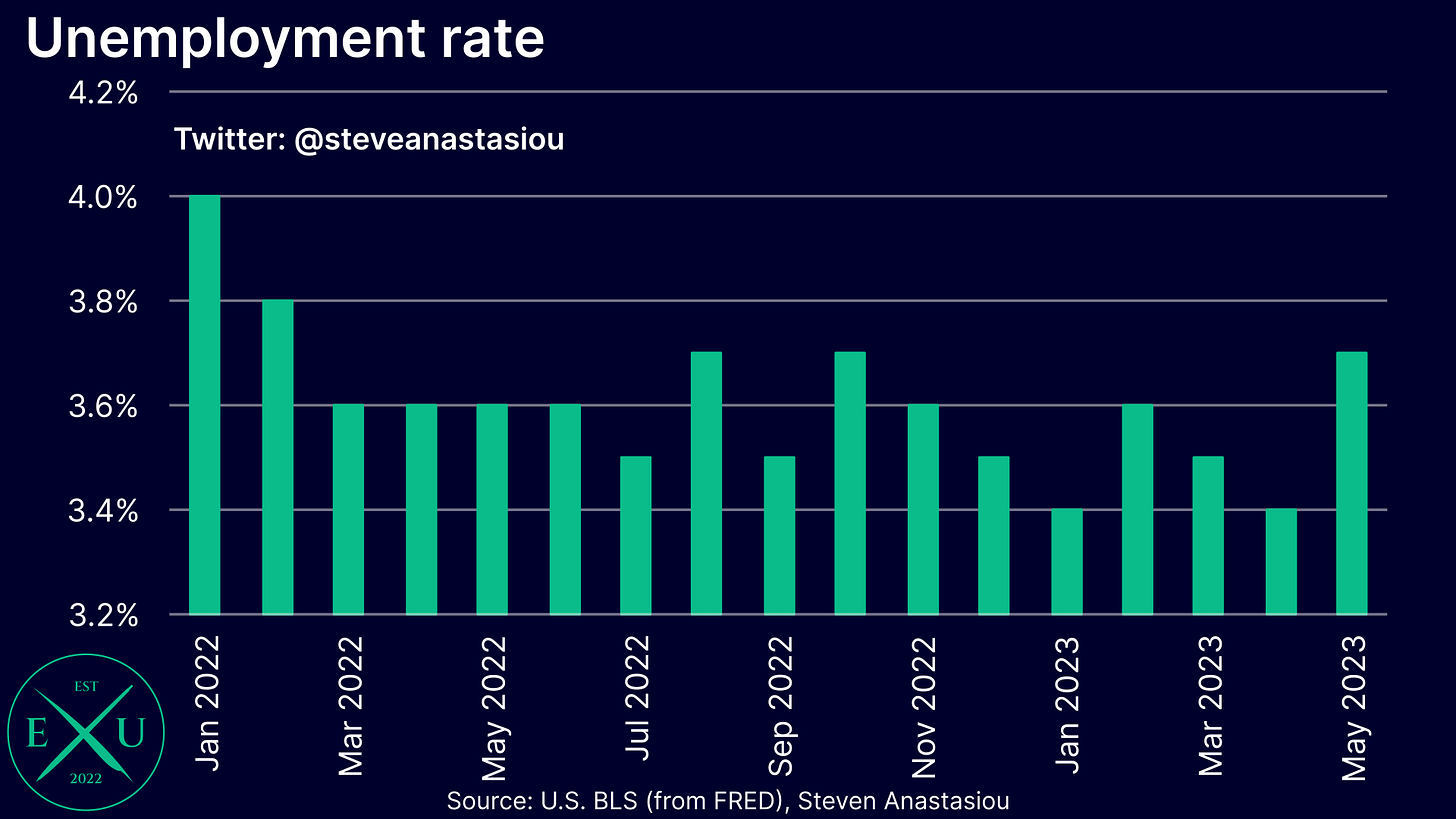

Beginning our review of the US jobs market with the unemployment rate, we can see that at 3.7%, unemployment remains historically low.

While relatively low by historical levels, zooming in to analyse more recent trends, shows that May’s rise in the unemployment rate took it to its highest level since October 2022.

In order to prompt more concern from the Fed, and a more nuanced approach to its monetary policy, the unemployment rate will likely need to show a clear upward trend, and break above 4.0%, which would represent a material weakening from the trough unemployment rate.

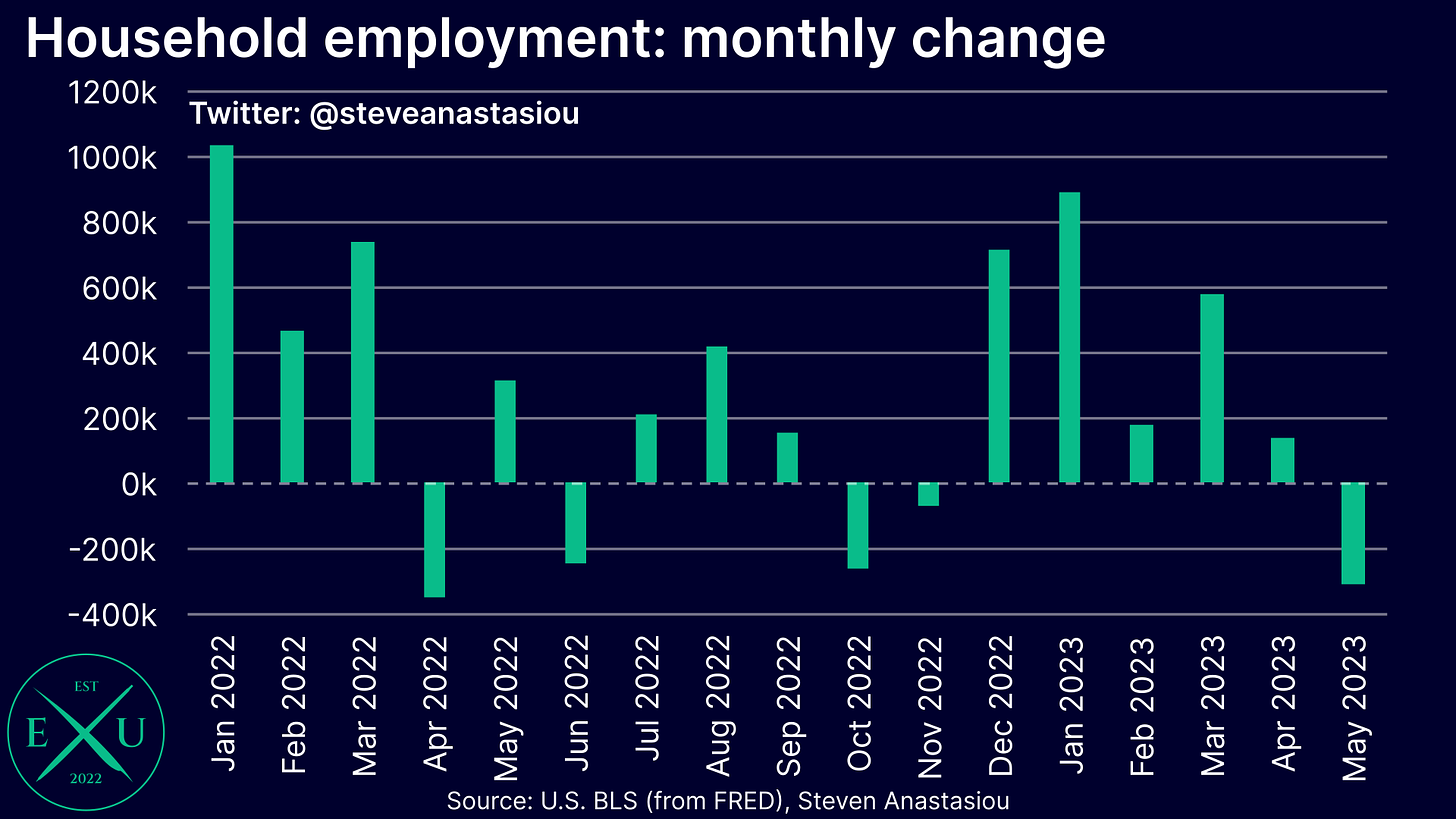

The increase in the unemployment rate follows a decline in household employment of 310k in May — its largest monthly decline since April 2022.

In contrast to the more volatile household survey, the establishment survey saw another month of strong growth, with 339k nonfarm payrolls estimated to have been added in May.

After major downward revisions in April (February revised down 78k, March revised down 71k), upward revisions were seen in May (March revised up 52k, April revised up 41k).

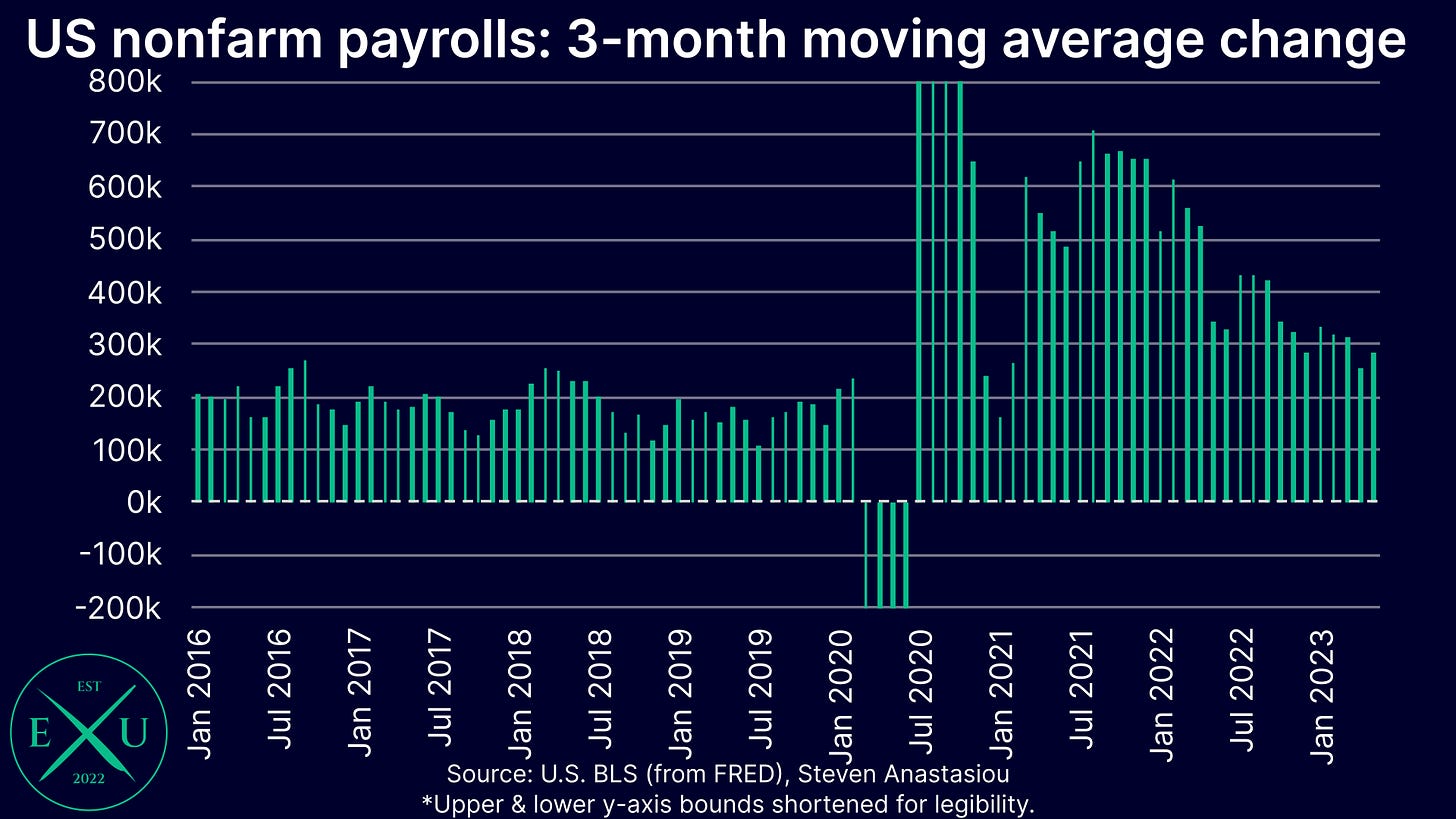

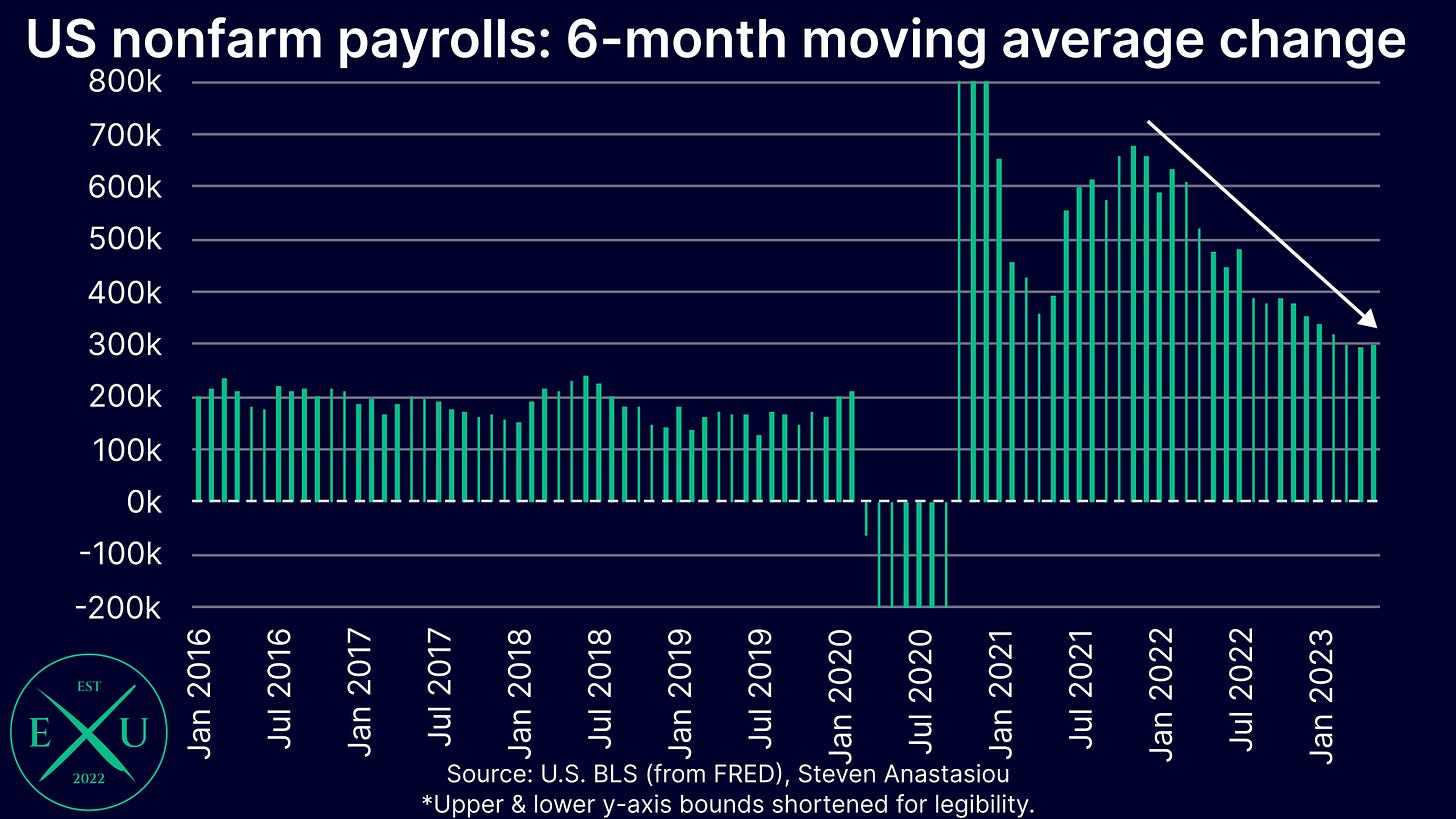

Given the MoM volatility of jobs market data, it’s best to look at employment changes on a 3 or 6-month moving average basis. On both a 3, and 6-month moving average basis, one can see an ongoing downtrend in employment growth — though current growth rates remain solid by historical standards.

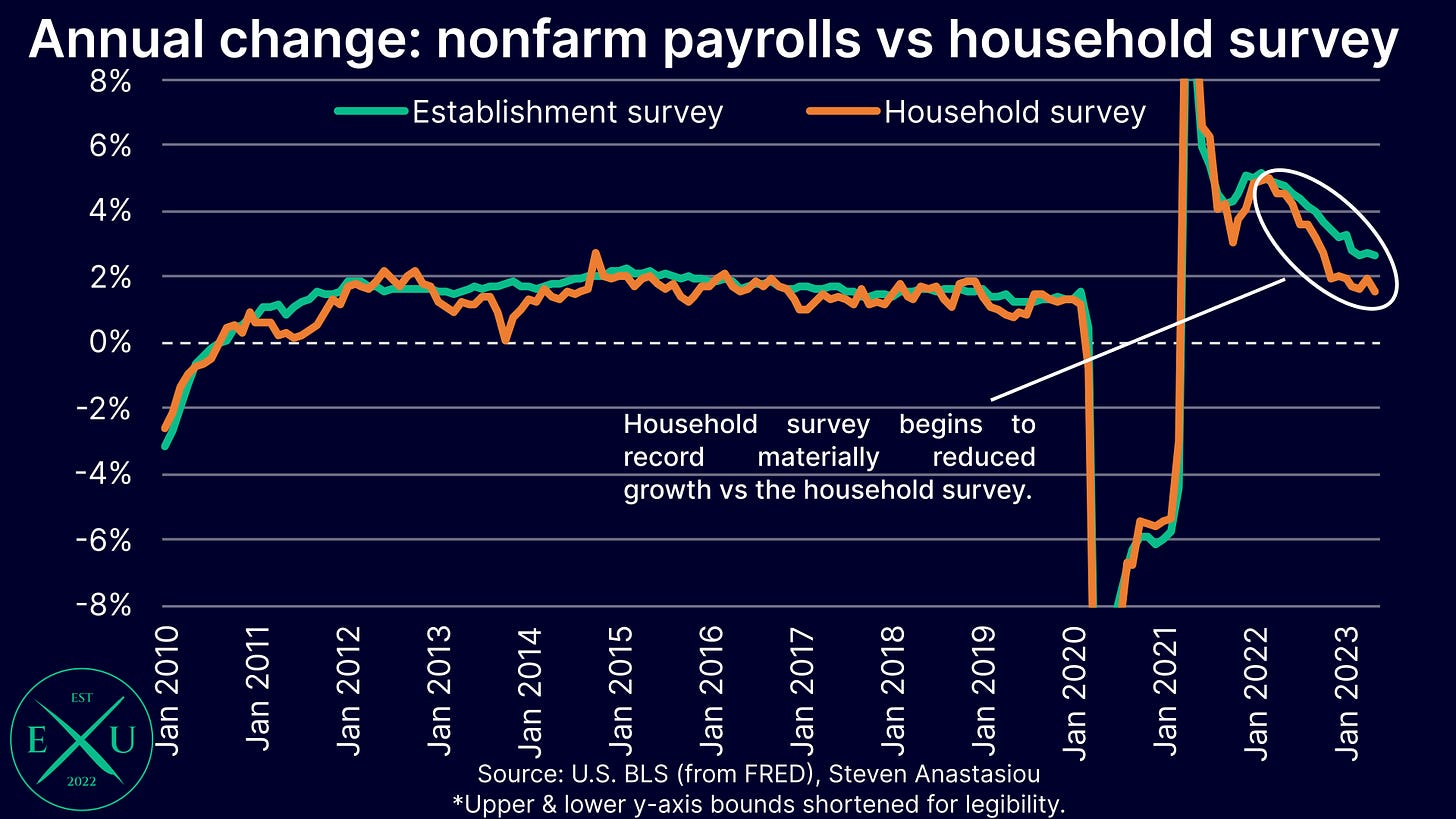

Comparing the annual growth rates of the household and establishment surveys, the household survey continues to show much lower growth than the establishment survey — a shift that began in 2Q22, and strengthened in 2H22.

While ongoing major differences between the establishment and household surveys suggest that the monthly establishment survey could be incorrectly estimating net business opening/closings, the latest comprehensive QCEW employment data (which includes data up to Q3 2022), does not show a major deviation between the monthly establishment survey.

Future QCEW data releases will be important to monitor to see if a material divergence opens up between the comprehensive QCEW data, and the monthly CES establishment survey, which would suggest that the monthly establishment survey’s net birth/death model is starting to incorrectly measure net business creation. It’s important to note that this error is likely to become more prominent around major shifts in the economy, including around the beginning of recessionary conditions.

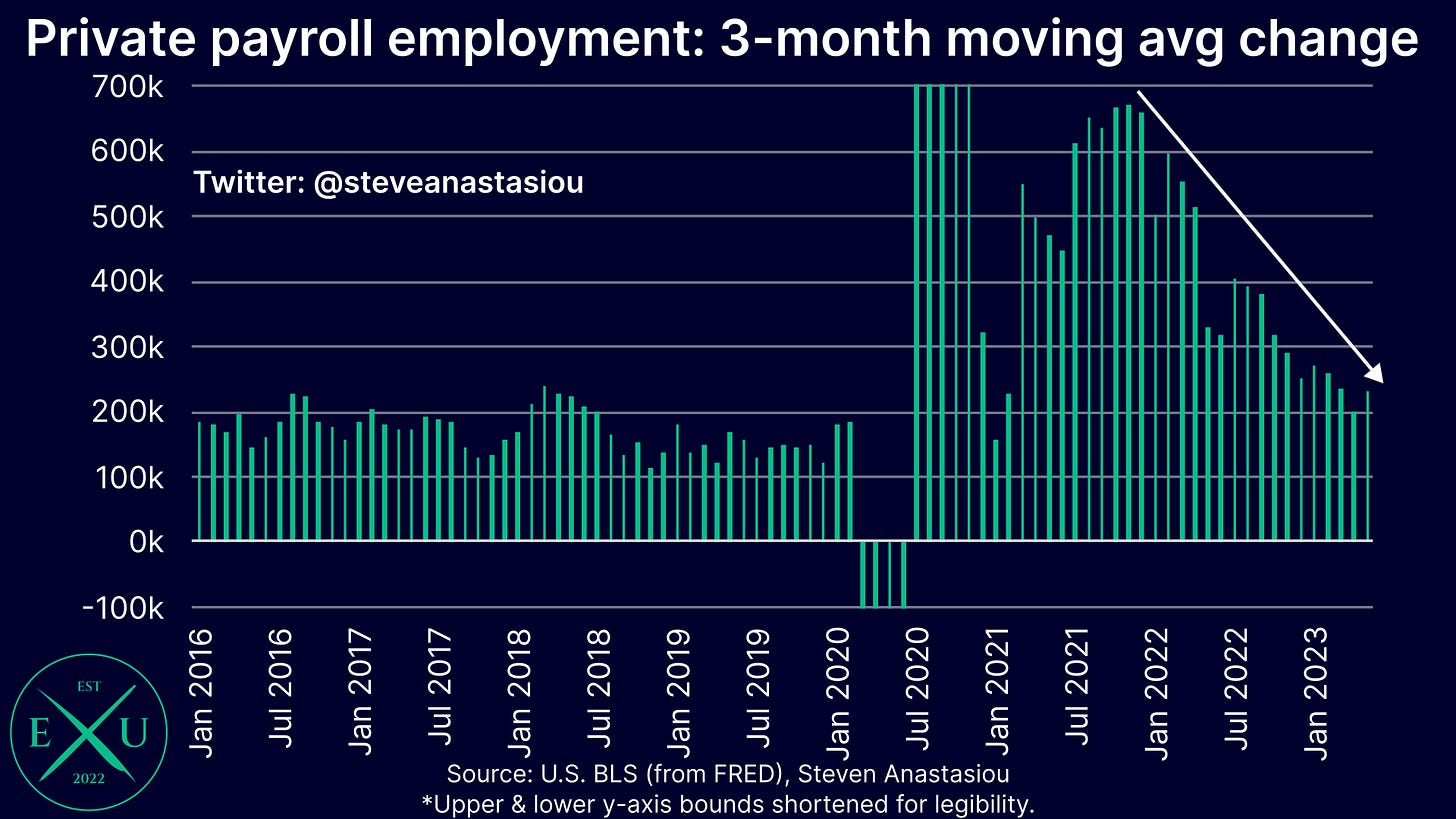

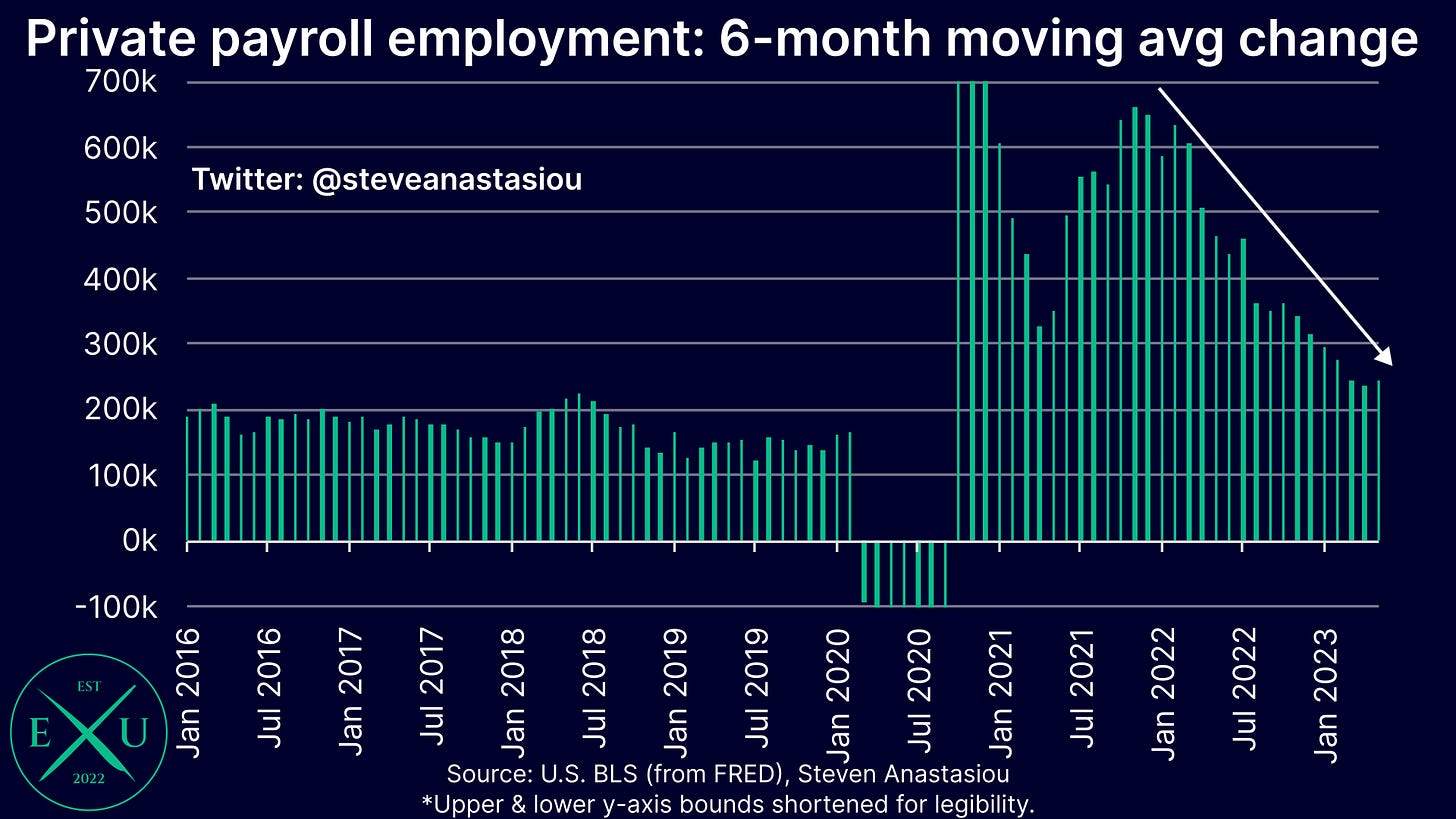

Digging deeper into the establishment survey, the decline in monthly employment growth can be more clearly seen in private employment, where growth is now back to levels that were seen pre-COVID.

The 6-month moving average change in private payrolls is also around historical pre-COVID averages.

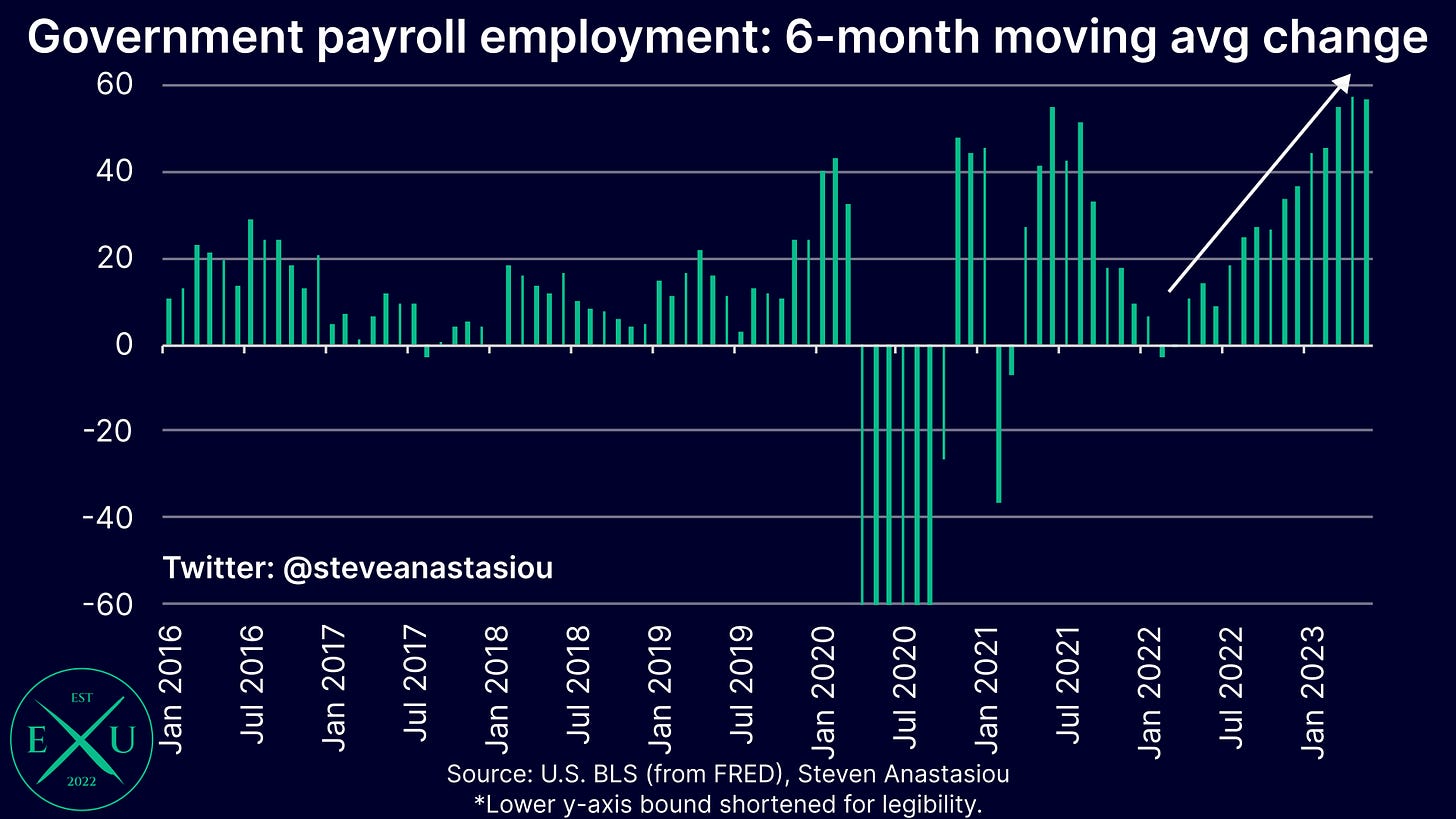

Given that overall monthly nonfarm payroll growth continues to be noticeably above its historical average (particularly so on a 6-month moving average basis), strength is being supported by government payrolls, which on a 6-month moving average basis, are above peak COVID rehiring levels.

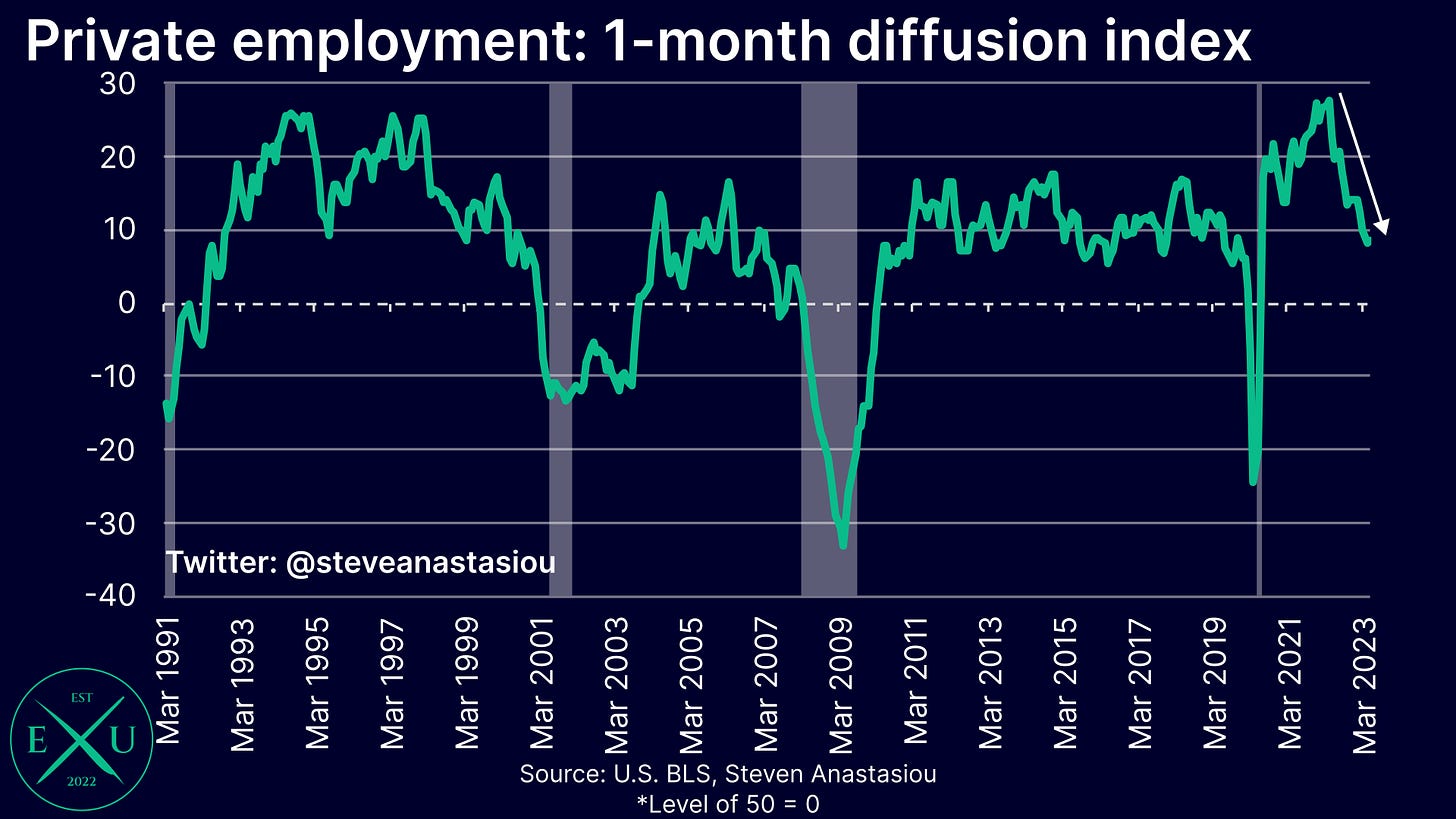

The private diffusion index, which measures the extent to which the number of private industries are recording employment growth or declines, continues to remain in a downtrend. Though currently, this weakening has only taken the index back to within its historical 2011-19 range.

With positive values continuing to be recorded, the majority of private employment industries are continuing to record payroll growth.

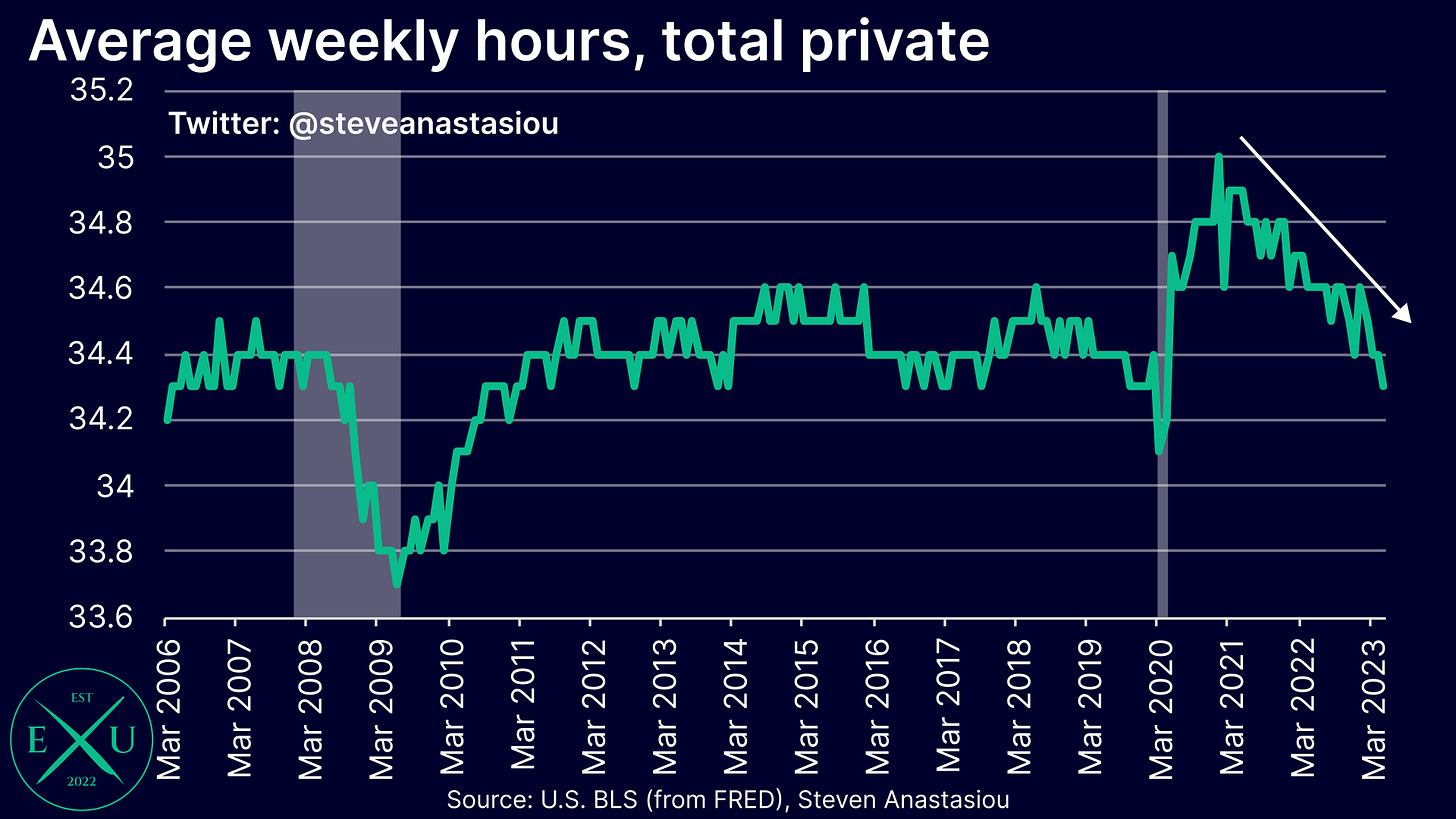

Turning towards average weekly hours, we can see that a more material weakening has taken place. In May, average weekly hours dropped to 34.3, the lowest level since April 2020.

Given the difficulties that employers had in finding enough workers to meet the artificially induced demand surge that enormous money printing created, they are likely to be particularly reluctant to cut staff during the current cycle. As a result, hours worked is likely to prove a more timely measure of a weakening employment market.

A further break to below 34.2, would see hours worked hit lows seen during the GFC and the subsequent economic recovery.

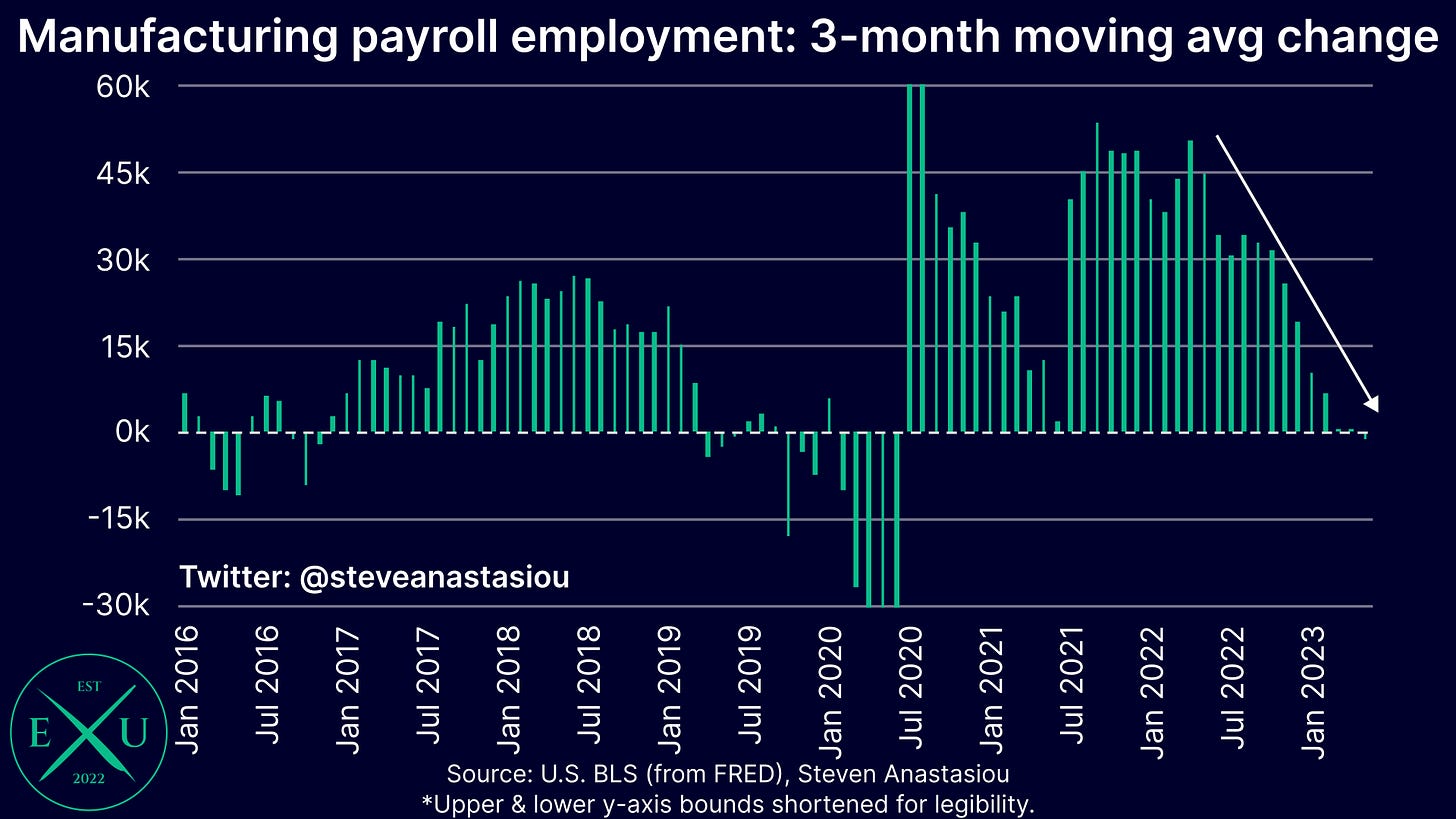

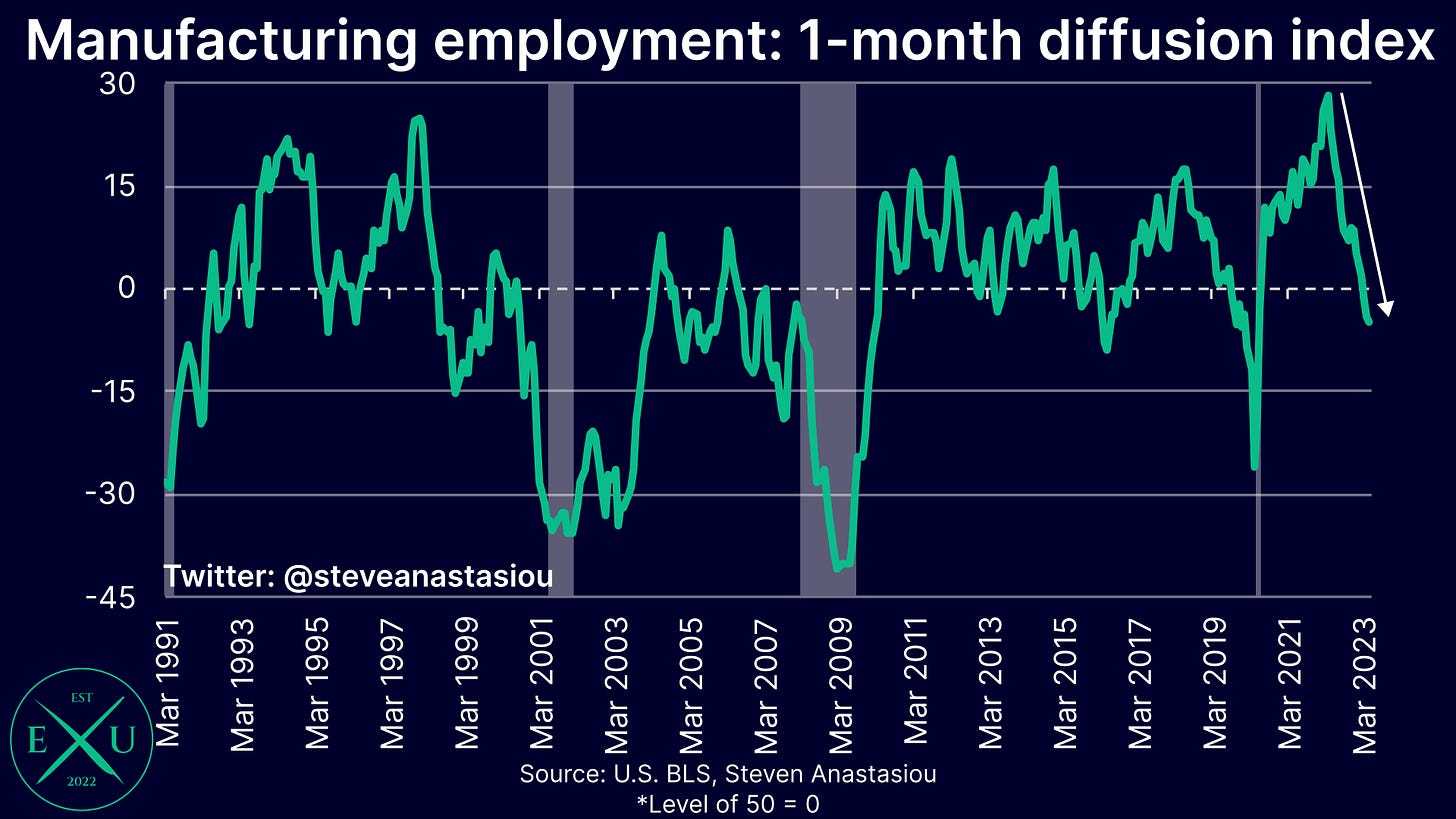

Looking at some of the more cyclical categories, manufacturing employment fell in May — the second decline in the last three months. The 3-month moving average change in manufacturing employment has now turned negative.

The manufacturing diffusion index recorded its fourth consecutive value below 50 — which says that a majority of manufacturing industries have been recording employment declines.

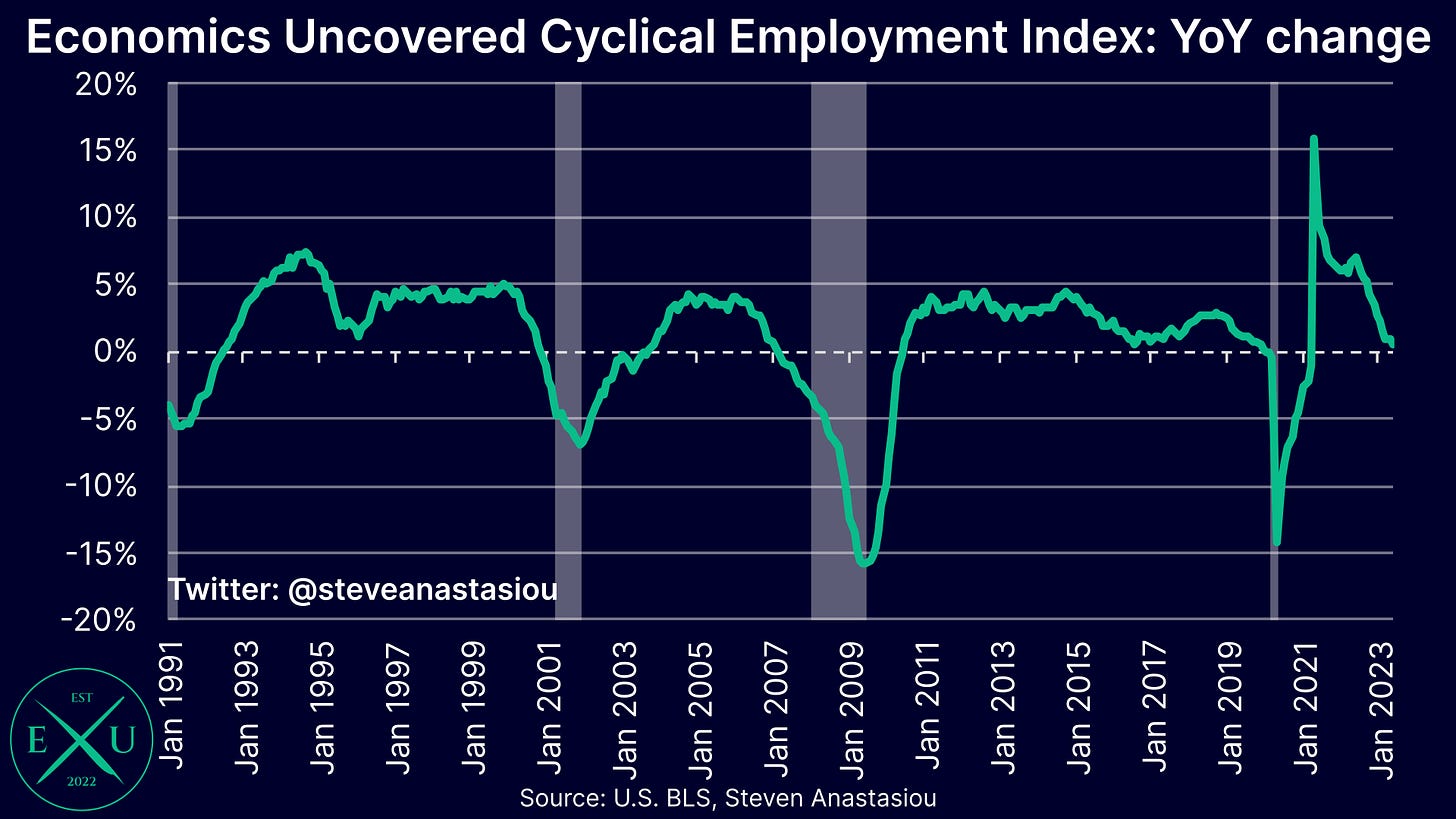

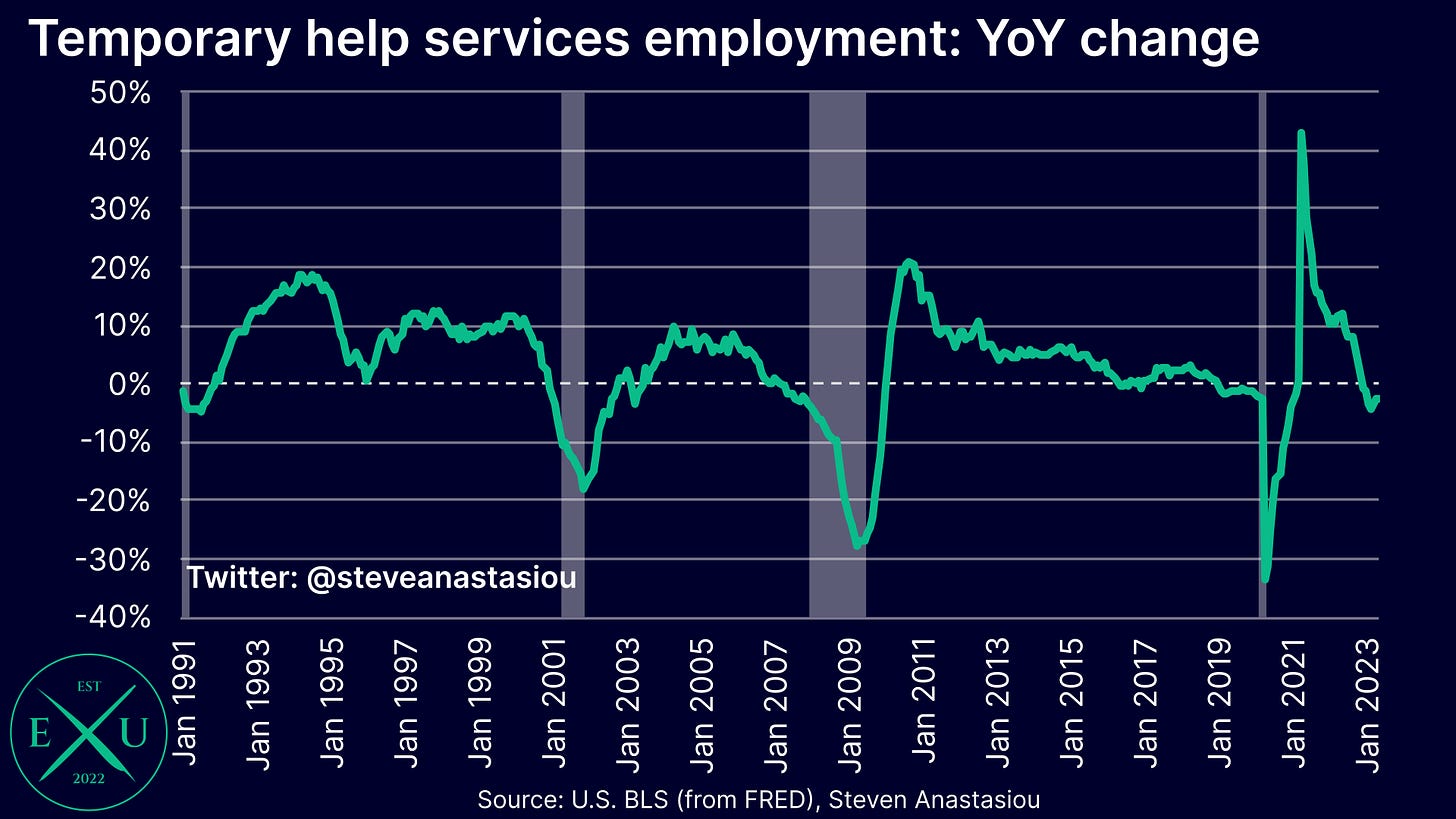

Looking more broadly at cyclical employment, the Economics Uncovered Cyclical Employment Index, which includes a number of leading categories of establishment survey employment, such as temporary help services employment, shows that annual growth continues to decline, falling to just 0.6% in May.

One of the components of the index, temporary help services employment, recorded annual employment growth of -2.6% in May.

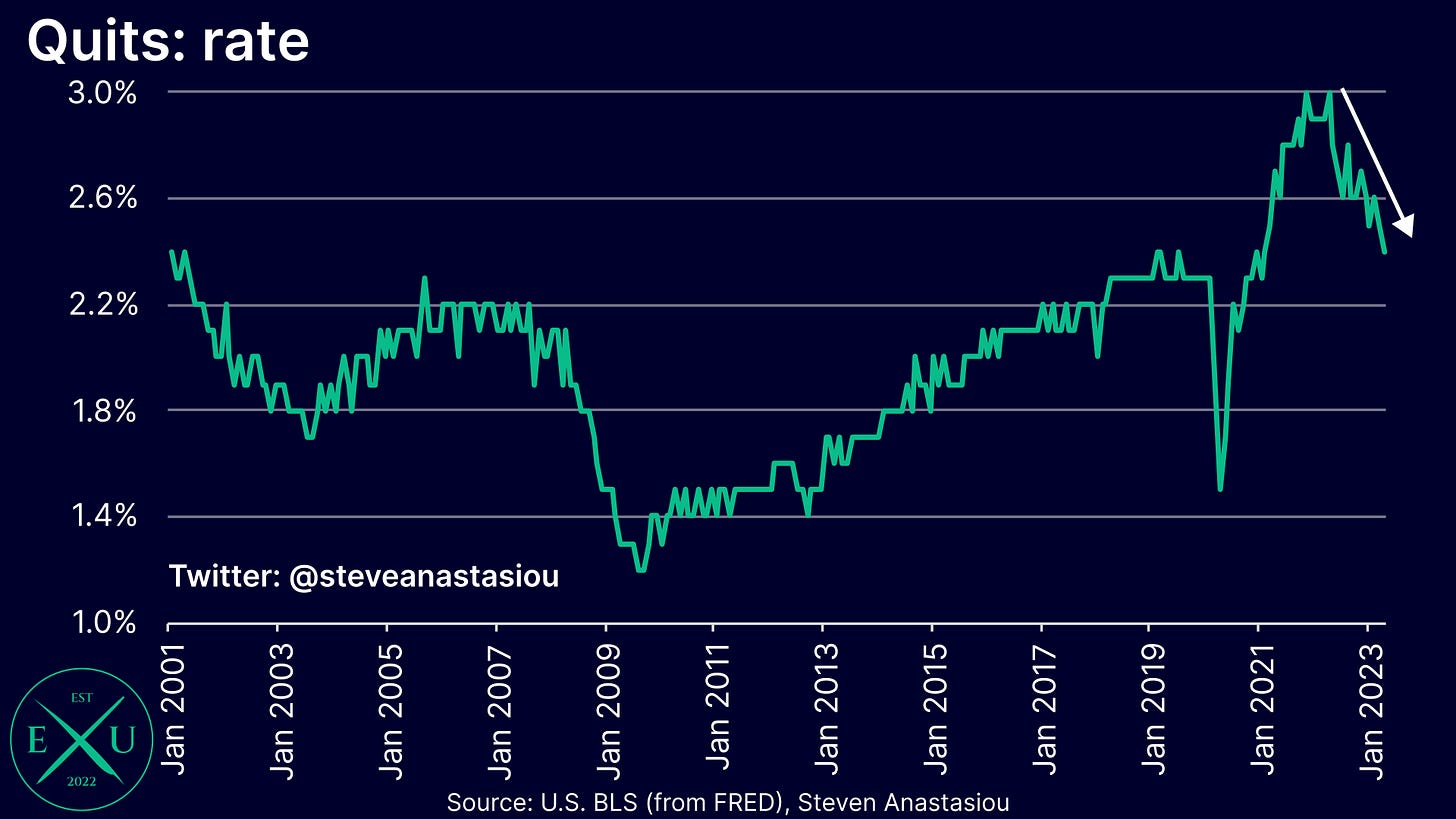

Turning to the rate of hires, quits and fires, one can see that the rate of quits continues to fall, indicating: 1) reduced confidence from employees that they can find better work elsewhere; and 2) a reduction in competition between firms to poach employee talent. While both are signs of a weakening employment market, the rate of quits continues to remain at an historically elevated level.

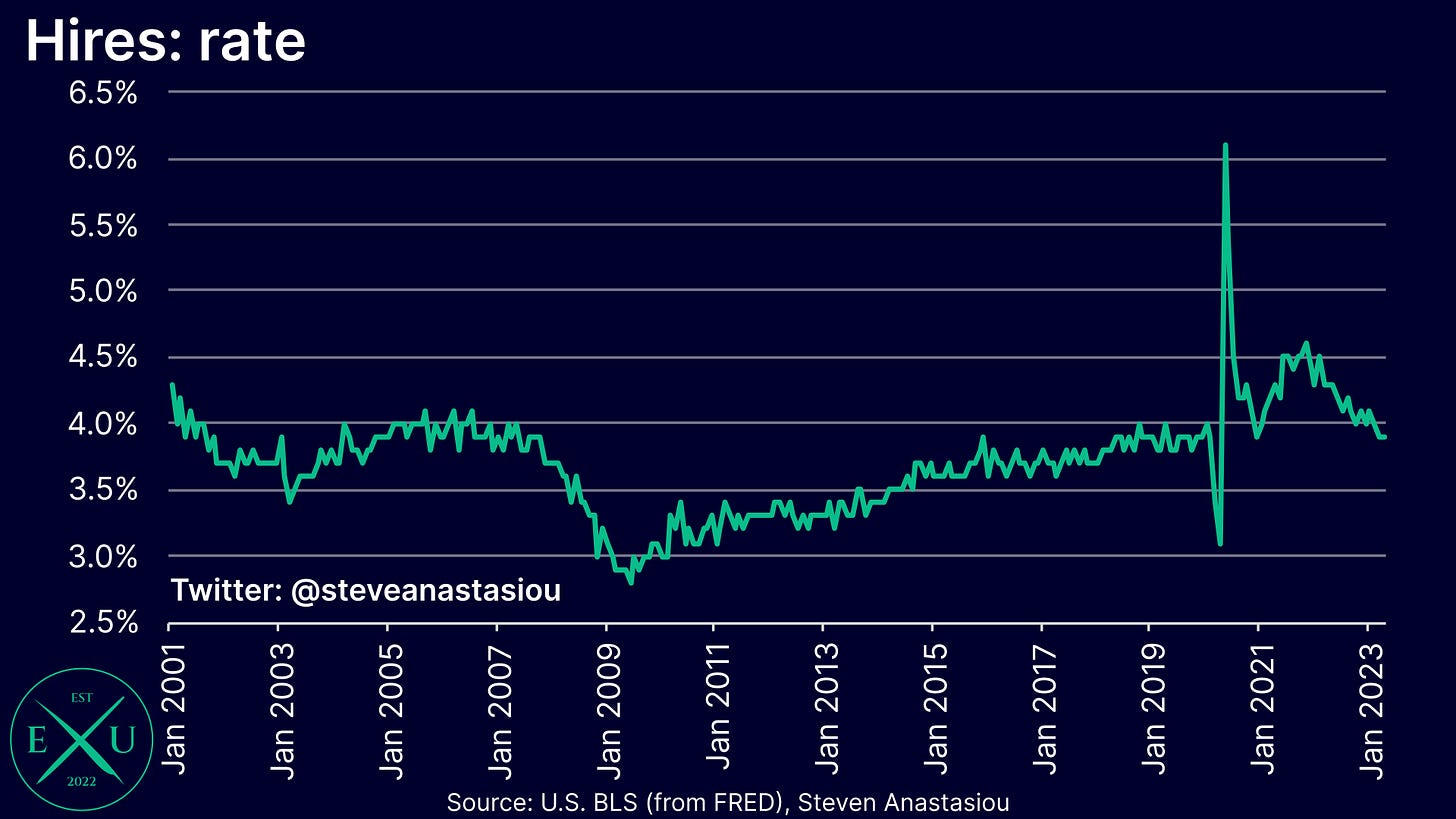

A decline in the rate of hires is again suggesting a weakening employment market. Here, the level has fallen to levels that have been seen historically, but not to a point that indicates a major deterioration in the employment market.

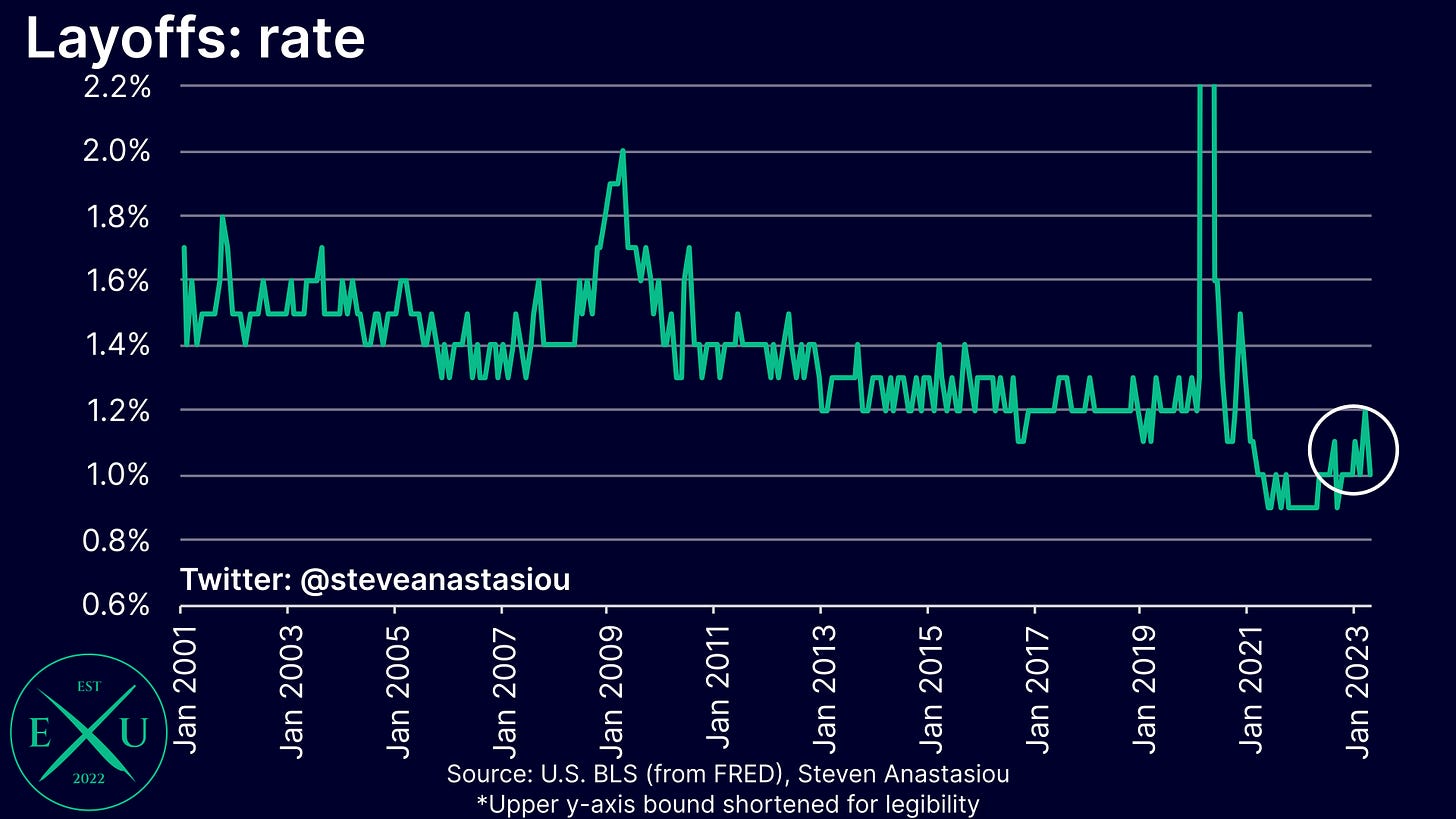

The relative robustness of the current employment market is further reinforced by the rate of layoffs, which remain at historically low levels. Though as earlier articulated, it’s important to remember that layoffs are likely to be a particularly lagging measure during the current economic cycle, given the difficulty that employers previously had in finding enough staff to meet an artificial surge in demand.

Hires and quits, which are both showing clear signs of moderating, are likely to be more timely indicators of a major shift in the health of the employment market.

After analysing both the trend and current state of the employment market, it’s important to also incorporate some broader economic context. The most important point here, is the Fed’s aggressive tightening, which has seen very large interest rate increases, and a shift from enormous growth in the M2 money supply, to the largest annual declines in M2 since the Great Depression.

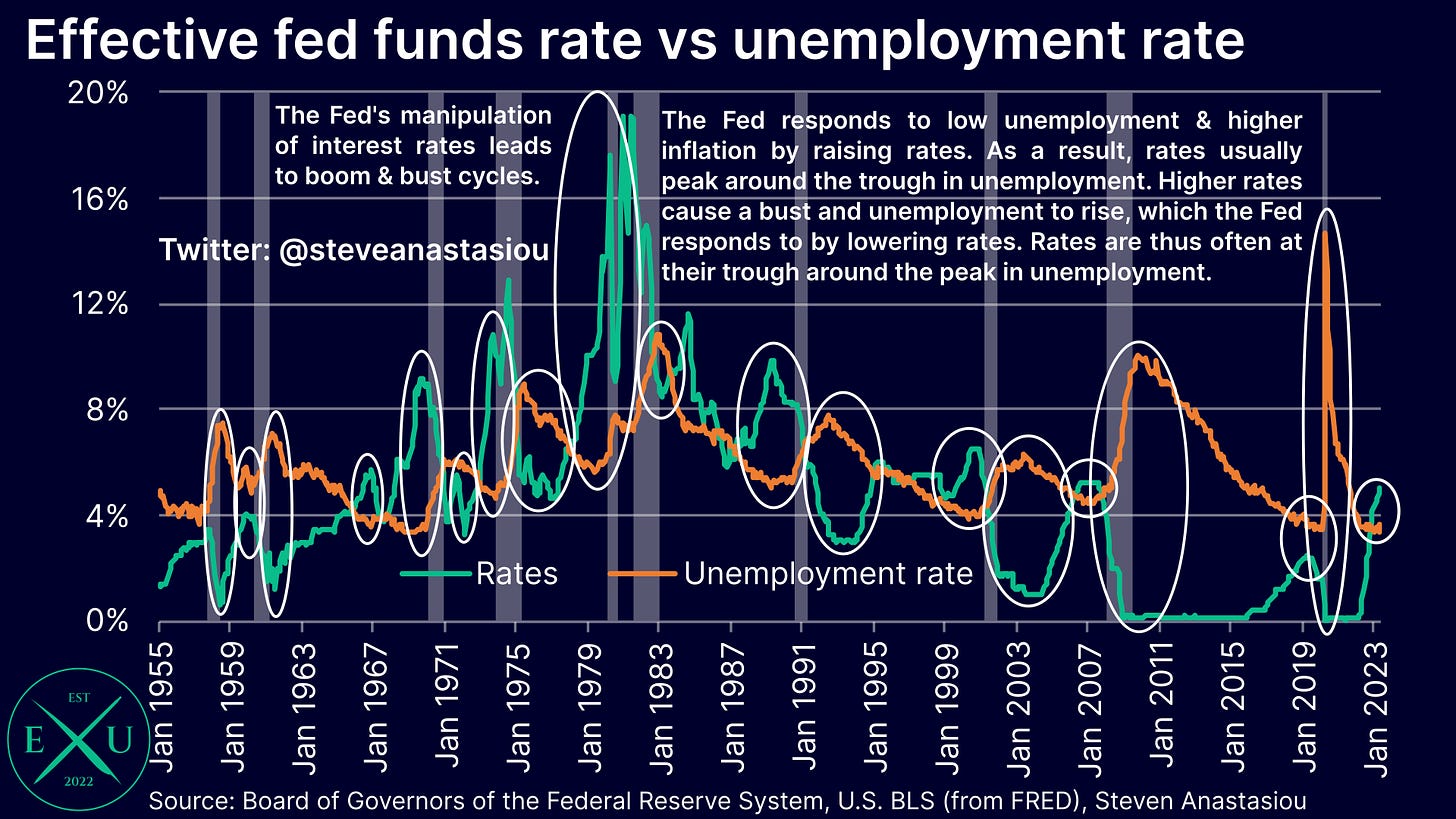

Given the enormous impact that changing the cost, and supply of, money, has on the wider economy, the Fed’s tightening/loosening cycles are the key driver of business cycles.

In order to respond to high unemployment and stimulate growth, the Fed loosens monetary policy. In order to respond to relatively high inflation and low unemployment, the Fed tightens monetary policy to reduce growth.

For this reason, interest rates tend to be at their trough when the unemployment rate peaks, while interest rates tend to peak when the employment rate troughs.

In light of an employment market that remains relatively robust, but one which is showing many signs of a gradual weakening, it’s important to remember the direction in which the Fed’s policy is likely to drive unemployment: higher.

As opposed to a relatively low unemployment rate indicating that this time is “different”, this time is simply following the same script that it’s historically followed — unemployment is generally relatively low before the bust, which is what prompts aggressive Fed tightening. The bust follows with a lag.

Thank you for reading — I hope you enjoyed my latest research piece.

In order to help support my independent economics research, please consider liking and sharing this post, which provides a great help in growing Economics Uncovered, and allowing me to continue to provide you with independent economics research that is free of government or corporate influence.

Please feel free to leave any comments below, to which I will endeavour to respond.

If you haven’t already subscribed to Economics Uncovered, subscribe below so that you don’t miss an update.