Unpacking the US Economy and Markets: a detailed review and outlook

At ~9,500 words, this update provides highly detailed insights into the current state and trajectory of the US economy, as well as the implications for financial markets.

In order to provide subscribers with significant additional value, I am pleased to release my latest report — a ~9,500 word review and outlook of the US economy and financial markets.

In addition to this post and email, I have decided to include this report within a dedicated section of the Economics Uncovered website, which you can access here at any time (consider bookmarking this link for easy access).

By including this report within its own dedicated section of the Economics Uncovered website, I will be able to make revisions as new data trickles in, as opposed to preparing an entirely new update, which is a very time-consuming process. I expect that this will allow for more timely updates to be delivered to this extensive review and outlook, whilst not detracting from my current publishing schedule.

Premium subscribers can review my most up-to-date review and outlook at any time by using the above link and I intend to make a note of when I have made revisions within my regular research updates that you receive in your email inbox.

While I have made some of this research report available to all subscribers, given that Economics Uncovered is an independent, reader-supported publication, in order to access the full report and any future revisions, a premium subscription will be required. To view the current monthly and annual subscription options, click the button below — your support is greatly appreciated and helps to ensure the continued delivery of the independent, institutional grade research, that Economics Uncovered provides.

Report outline

Executive summary

Money supply, bank credit & liquidity

M2 begins to rise, but growth remains relatively constrained

Bank credit impacted by higher interest rates and QT, but it has returned to growth

Abundant liquidity and a large federal government deficit drives bank deposit growth, stimulating the economy and breaking the link to QT

While the RRP boost is getting closer to an end, a broadly favourable liquidity backdrop is expected in 2H24 — but will it be enough to materially boost the US economy?

GDP, personal spending and income

Second revision reveals a moderation in real final sales to domestic purchasers growth as real PCE growth moderates materially

The major decline in real disposable income growth may be reaching a tipping point for the wider economy

While a material economic slowdown looks likely to occur this year, base effects will help to support growth in 2Q24

Employment

While job gains appear strong, they aren’t even keeping up with population growth

A major weakening has been seen across a broad array of labour market measures

The pathway of least resistance is for a further weakening, which could see the unemployment rate move sharply higher — even if job growth remains positive

Inflation

CPI growth materially decelerates a month earlier than expected as services prices see broad disinflation

From vehicle price trends to wage growth to spot market rents, the reasons for significant 2H24 disinflation are numerous

CPI growth is now tracking below my latest medium-term US CPI forecast

The PCE Price Index tends to grow at a materially slower pace than the CPI

Overarching US Economic Summary & Outlook — continued expansion or a recession?

Fed policy outlook

Market overview & outlook

The impact of the Fed’s decision to taper QT

Stages of the Economic Cycle — investment implications

Equity market review

Equity market outlook

Bond (Treasury) market review

Bond (Treasury) market outlook

Important disclaimer—this may affect your legal rights:

This report is an economics research publication and is not investment advice. This economics research represents my own analysis, opinions and views, is general in nature, and does not constitute personal advice to any person.

While research may make mention of potential financial market implications, this analysis is general in nature, is not investment advice and is only provided for informational and educational purposes in order to explain the potential impacts of potential economic policy and data outcomes. Any mention of potential financial market implications does not constitute personal advice to any person.

While this research utilises data which is considered to be reliable, I have not independently verified the accuracy of the data utilised in this research.

While the author has taken care to try and ensure that the figures, data and information presented in this research are accurate and free of errors, reports may contain errors or omissions that may become apparent after this research has been published.

Furthermore, this report may contain forward-looking statements, which are subject to inherent variability and are subject to risks and uncertainties. Forward-looking statements may be identified by the use of terminology, including, but not limited to, ‘anticipate’, ‘estimate’, ‘expect’, ‘may’, ‘forecast’, ‘trend’, ‘potential’ or similar words. Forward-looking statements are based on current expectations and reflect judgements, assumptions and estimates and other information available as at the date made. Forward-looking statements do not represent guarantees and are subject to significant uncertainties which may cause actual results to differ materially from the forecasts expressed in this report. As such, I caution against reliance on any forward-looking statements.

I do not represent, warrant or guarantee expressly or impliedly, that the data and information contained in this research is complete or accurate. I do not accept any responsibility to inform you of any matter that subsequently comes to my attention, which may affect any of the information contained in this research. I do not accept any obligation to correct or update the information or opinions contained in this research. I do not accept any liability (whether arising in contract, in tort or negligence or otherwise) for any error or omissions in this document or for any resulting loss or damage (whether direct, indirect, consequential or otherwise) suffered by the recipient of this document or any other person.

Executive summary

With price growth materially elevated across the first four months of the year and nonfarm payroll growth running at an historically strong pace, markets have drastically reduced their expectations for 2024 interest rate cuts from a peak of seven in January.

As a consequence, the 10-year Treasury yield has increased significantly from 3.88% at the end of 2023 to 4.25% at the time of writing.

Though despite the YTD increase, the 10-year yield is down materially from the recent peak of 4.62% on 29 May. The recent softening in yields comes after May’s US CPI report showed major disinflation and a number of weaker economic data points have been seen, including: a notable downward revision to 1Q24 US GDP numbers; a MoM decline in real disposable income for the second time in the past three months; and a MoM decline in real personal consumption spending.

The latest CPI report and recent softening of economic data align with my expectations for a material slowdown in the US economy and material disinflation during 2H24.

Key points to note in support of these expectations include:

Real disposable income growth falling to just 1.0% YoY;

Real personal consumption expenditure being unsustainably propped up by falling savings rates, which are now well below the 2015-19 average;

The US employment market showing broad signs of a major weakening (including material and ongoing increases in the unemployment rate);

Increasingly large declines in cyclical durable goods prices;

Declining spot market rents; and

Moderating wage growth.

While higher immigration and a more favourable liquidity and bank deposit outlook for 2H24 versus 2Q24 mean that my base case is for the US economy to avoid a recession in 2024, the clear (and growing) risk is that a continued weakening of the employment market tips the US into a recession in 2H24 or 1H25.

Irrespective of whether the US enters a recession this year or not, I expect the combination of a slowdown in economic growth and inflation to result in at least two 2H24 rate cuts.

Despite the 10-year Treasury yield rising as high as 5% over the past year, US equity markets have recorded strong YoY increases as increased liquidity and relatively strong nominal economic growth have provided strong tailwinds.

The Fed’s decision to signal a near-term tapering of QT in March, and its formal announcement of a material tapering of QT in May whilst reserves remain in abundance, has had material implications for the liquidity outlook and has likely been a particularly important driver of asset prices in recent months, with the S&P 500 and Nasdaq up 9.0% and 14.1% respectively, since the Fed announced a material reduction in the pace of QT at its May FOMC meeting. Economics Uncovered subscribers have been kept well abreast of the importance of these developments via detailed prior research pieces (see “Fed turns increasingly dovish, adding further fuel to financial markets” published 21 March and “Why the Fed's reduction in the pace of QT is critical for markets” published 11 May).

While the combination of continued relatively solid nominal economic growth and a more dovish Fed have supported equities, I believe that markets are significantly underestimating the odds of a major slowdown in the US economy in 2H24.

Given the impact that a weakening economy may have on the interest rate and liquidity outlook, corporate earnings and investor confidence, this could have significant implications for asset markets and lead to a material increase in volatility in 2H24.

Given the recent inflationary experience, it’s also important to consider that the Fed may be materially less responsive to an economic weakening than in prior economic downturns, increasing the risk that the US economy enters a recession in 2H24 or 1H25, as well as its potential severity, with flow-on implications for asset markets.

A detailed analysis of the potential implications for equities and Treasuries is included in the report below.

Money supply, bank credit & liquidity

In order to understand the outlook for the US economy, it’s important to firstly analyse how current fiscal and monetary policy has, and is, impacting the money supply, bank credit and overall liquidity — in doing so, I will begin with an overview of shifts that have been seen in the M2 money supply, before moving on to analyse its underlying drivers.

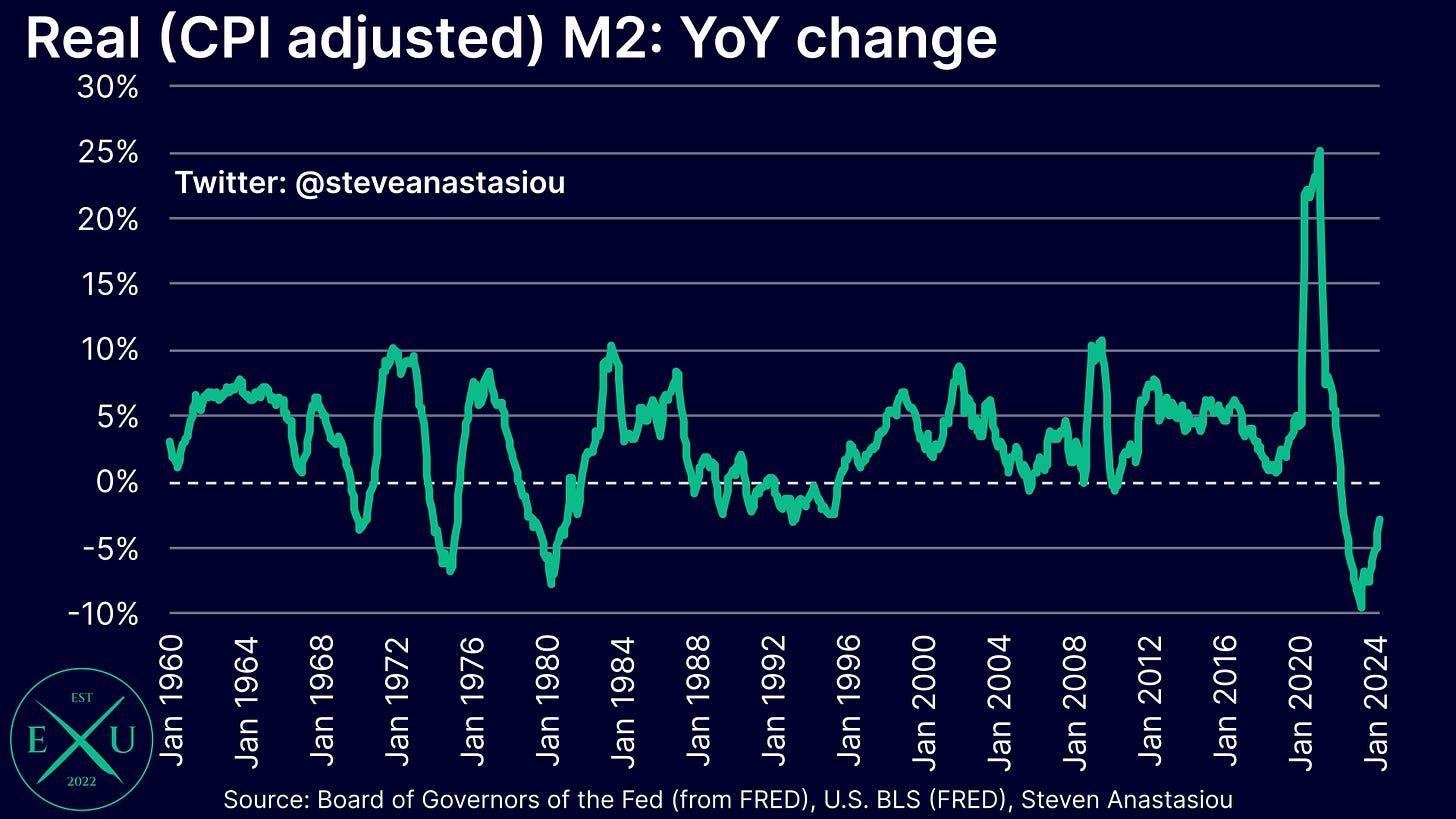

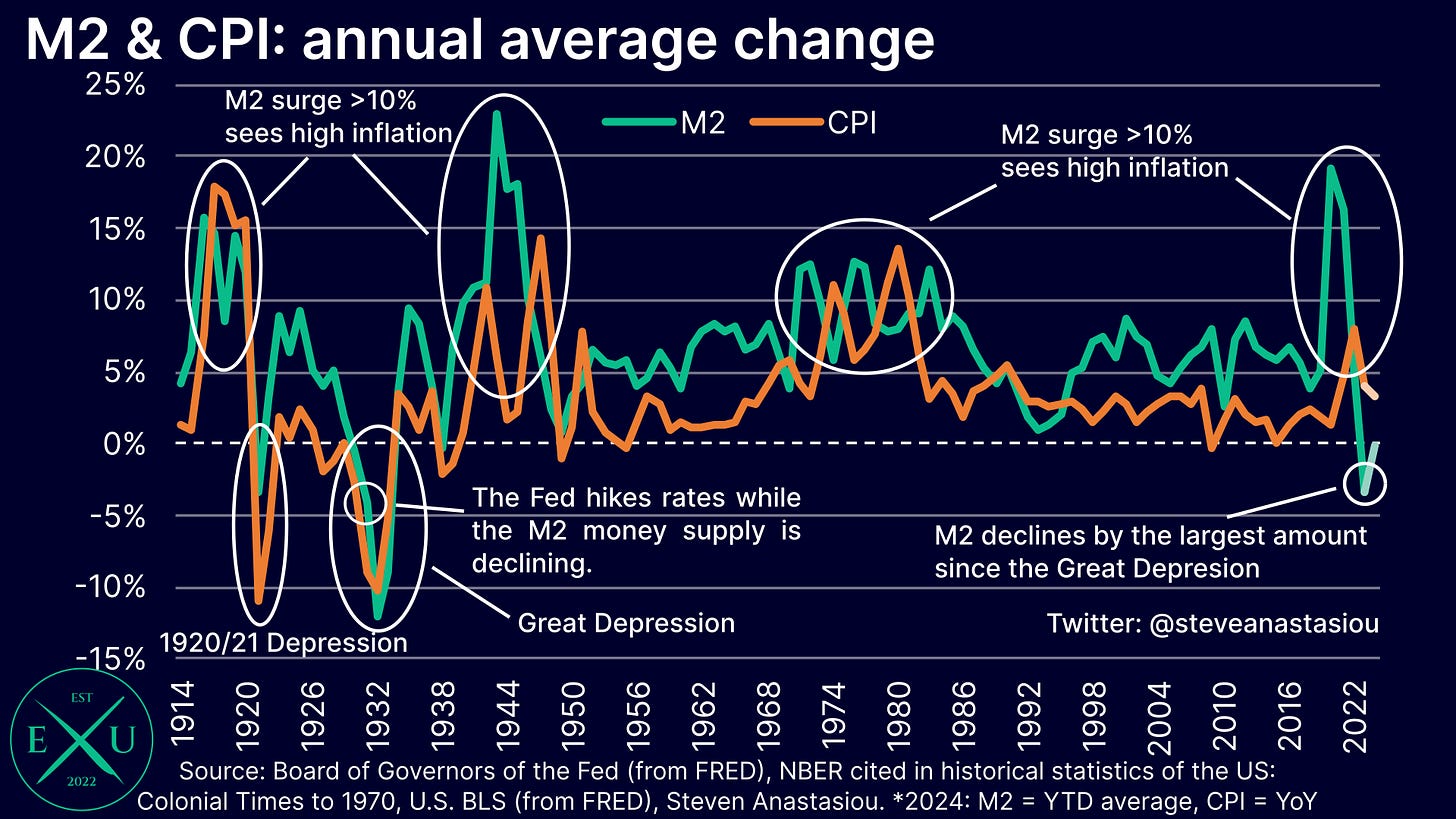

M2 begins to rise, but growth remains relatively constrained

YoY growth in the M2 money supply (M2) was 0.53% in April, marking the first time that M2 has recorded YoY growth since November 2022. While growth is now materially above the trough of -4.6% YoY that was recorded in April 2023, the current YoY growth rate indicates that M2 continues to remain relatively constrained by the Fed’s monetary policy tightening — and particularly so on an inflation-adjusted basis. This is likely to place further downward pressure on inflation, as well as nominal economic activity, over the medium-term.

On a 3- and 6-month annualised basis, M2 rose by 2.2% and 1.7% respectively, in April. This indicates that the YoY growth rate of M2 is likely to turn increasingly positive over the months ahead.

Though even on these shorter-term time frames, M2 growth remains modest and well below the average monthly growth rate of 5.8% YoY that was seen across 2010-19 and the current 10-year moving average growth rate of 6.8% YoY.

M2 also remains negative on an annual average basis. Historically, annual average declines in M2 have been strongly correlated with deflationary busts. While the current liquidity backdrop (which is discussed in detail below) suggests that a deflationary bust is not imminent, the annual average change in M2 nevertheless continues to point to further disinflation and moderating nominal economic growth, as being likely over the medium-term.

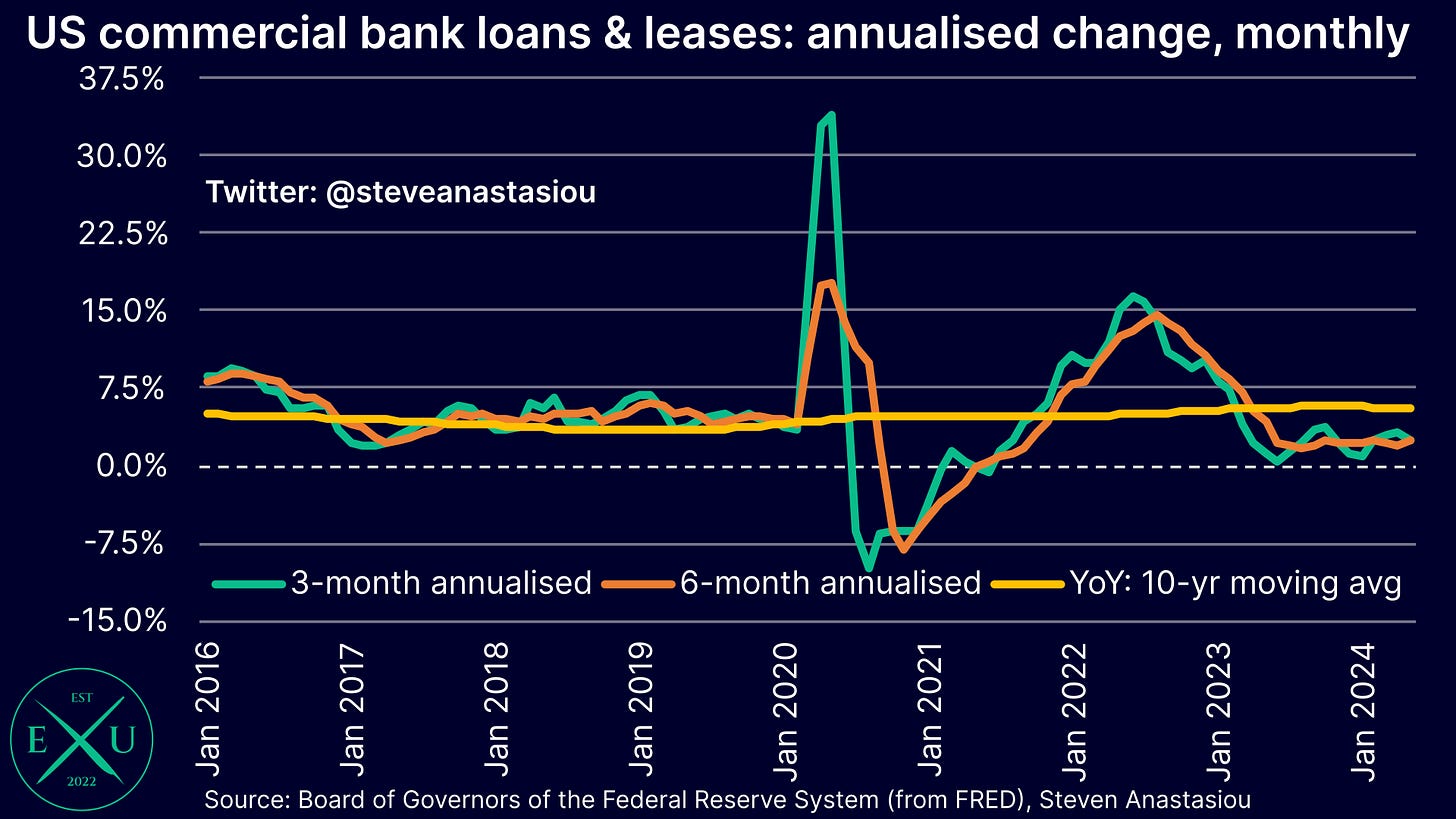

Bank credit impacted by higher interest rates and QT, but it has returned to growth

In order to determine how the Fed’s tightening has worked its way through to the money supply, we can examine bank credit and its key components, being commercial bank loans and leases (which have been particularly impacted by the Fed’s significant interest rate increases), and commercial bank security holdings (which have been particularly impacted by QT).

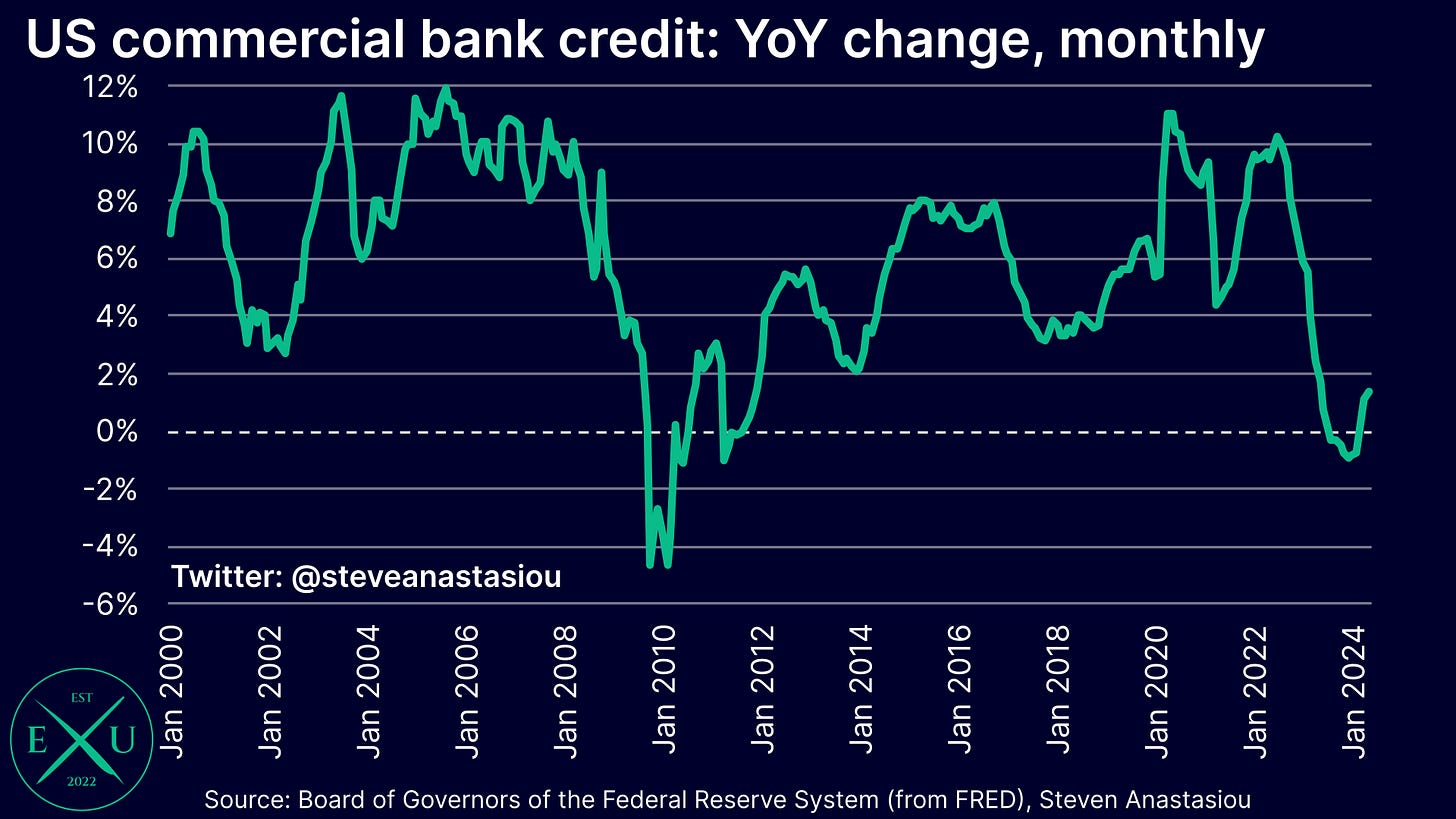

Looking firstly at commercial bank loans & leases, growth has plunged from a peak of 12.2% YoY in October 2022, to just 2.3% in May.

More recent data shows that both 3- and 6-month annualised growth remains modest at 2.4%, which is well below the 10-year moving average growth rate of 5.6% YoY.

While showing that the Fed’s interest rate hikes have had a clear and significant impact, they have not been large enough to encourage an outright deleveraging, with the outstanding level of loans continuing to grow.

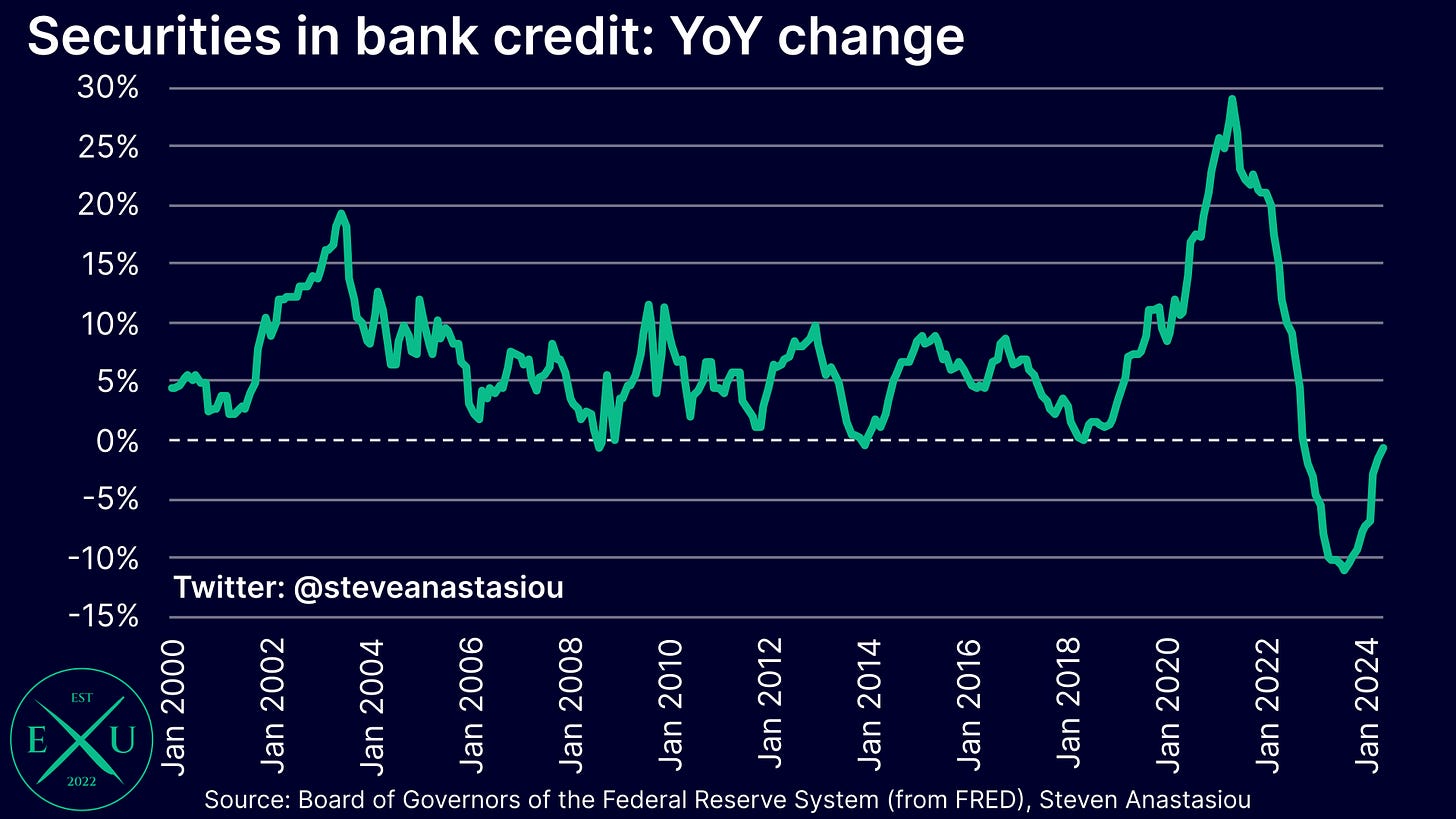

Turning to commercial bank securities held in bank credit, the first thing to note is the impact of the Fed’s QT, which impacts securities held in bank credit via its impact on bank deposits. While the near 1:1 link has been broken by a significant decline in the Fed’s RRP facility (which is explained below), the below chart highlights the impact that both QE and QT have on bank deposits.

In regards to QT, to the extent that the Fed’s security holdings fall, private sector holdings increase. Given that the private sector uses bank deposits to purchase securities and the Fed’s balance sheet shrinks, QT acts to mechanically reduce both bank deposits and bank reserves. QE has the opposite effect, which explains the close correlation to increases in the Fed’s securities holdings and commercial bank deposits from ~March 2020-May 2022.

By acting to mechanically reduce bank deposits, QT places pressure on bank liquidity, as banks must use cash to fund deposit outflows. Given that selling securities is one way for banks to raise cash, this explains why there was a large decline in securities held in bank credit across much of 2022-23.

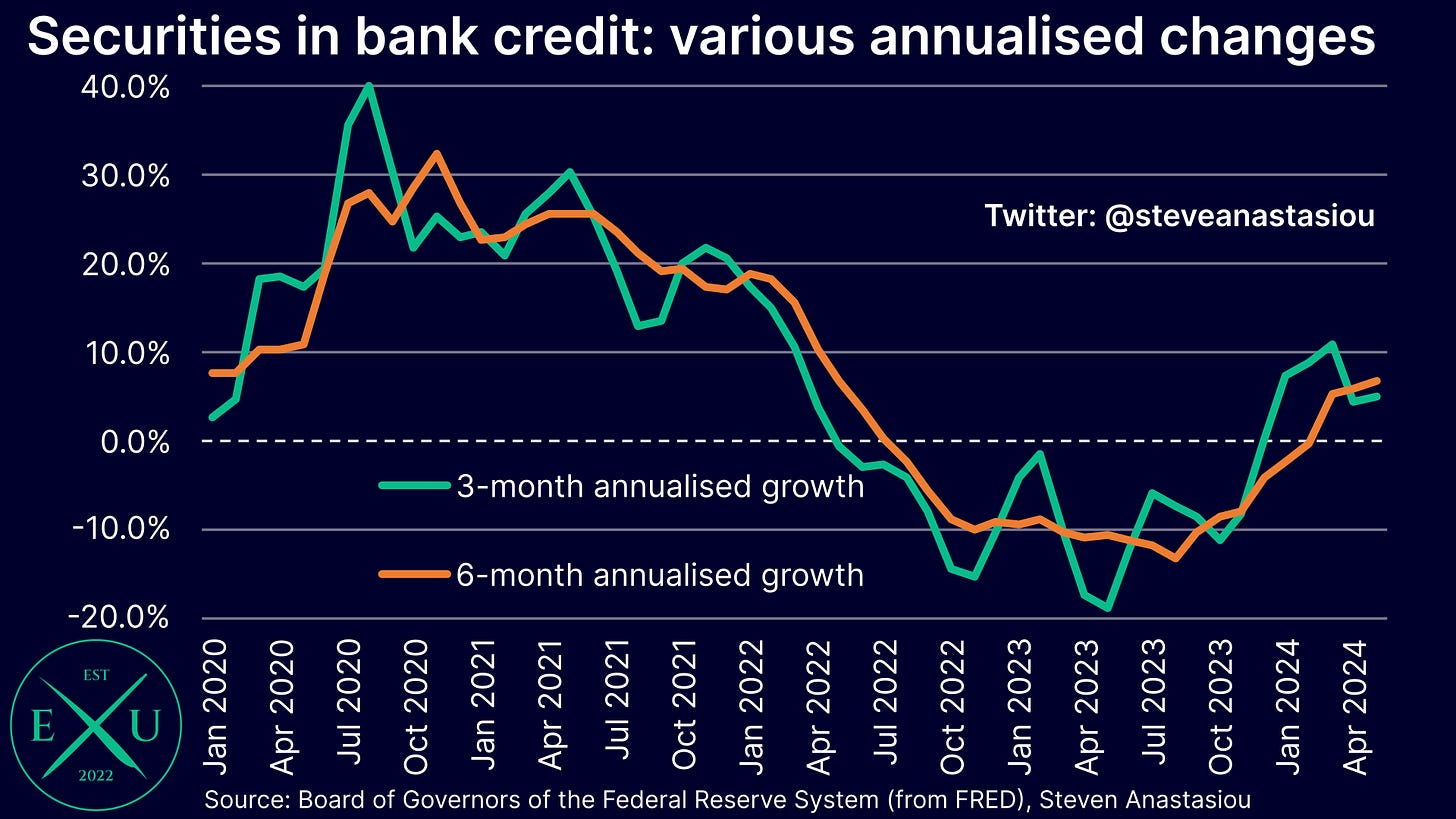

Though with bank deposits rising in recent months, so too have securities held in bank credit with 3- and 6-month annualised growth up by 4.9% and 6.8% respectively, in April.

This has reduced the rate of YoY decline from a trough of -11.0% in August, to -0.7% in April.

As a result of the significant deceleration in loan and lease growth and outright declines in commercial bank security holdings, for the first time since the aftermath of the GFC, bank credit saw YoY declines from August 2023-February 2024, with a trough of -0.9% YoY recorded in December 2023.

Though with loan and lease growth continuing and commercial bank security holdings returning to MoM growth in recent months, bank credit has once again turned YoY positive, rising to 1.4% in May. Despite returning to growth, this remains well below the 2010-19 average of 4.2% YoY.

On a 3- and 6-month annualised basis, commercial bank credit has grown by 3.1% and 3.7%, respectively.

Abundant liquidity and a large federal government deficit drives bank deposit growth, stimulating the economy and breaking the link to QT

Turning now to a discussion of liquidity levels, the two key factors to note are the very large federal government deficit and the Fed’s reverse repo (RRP) facility.

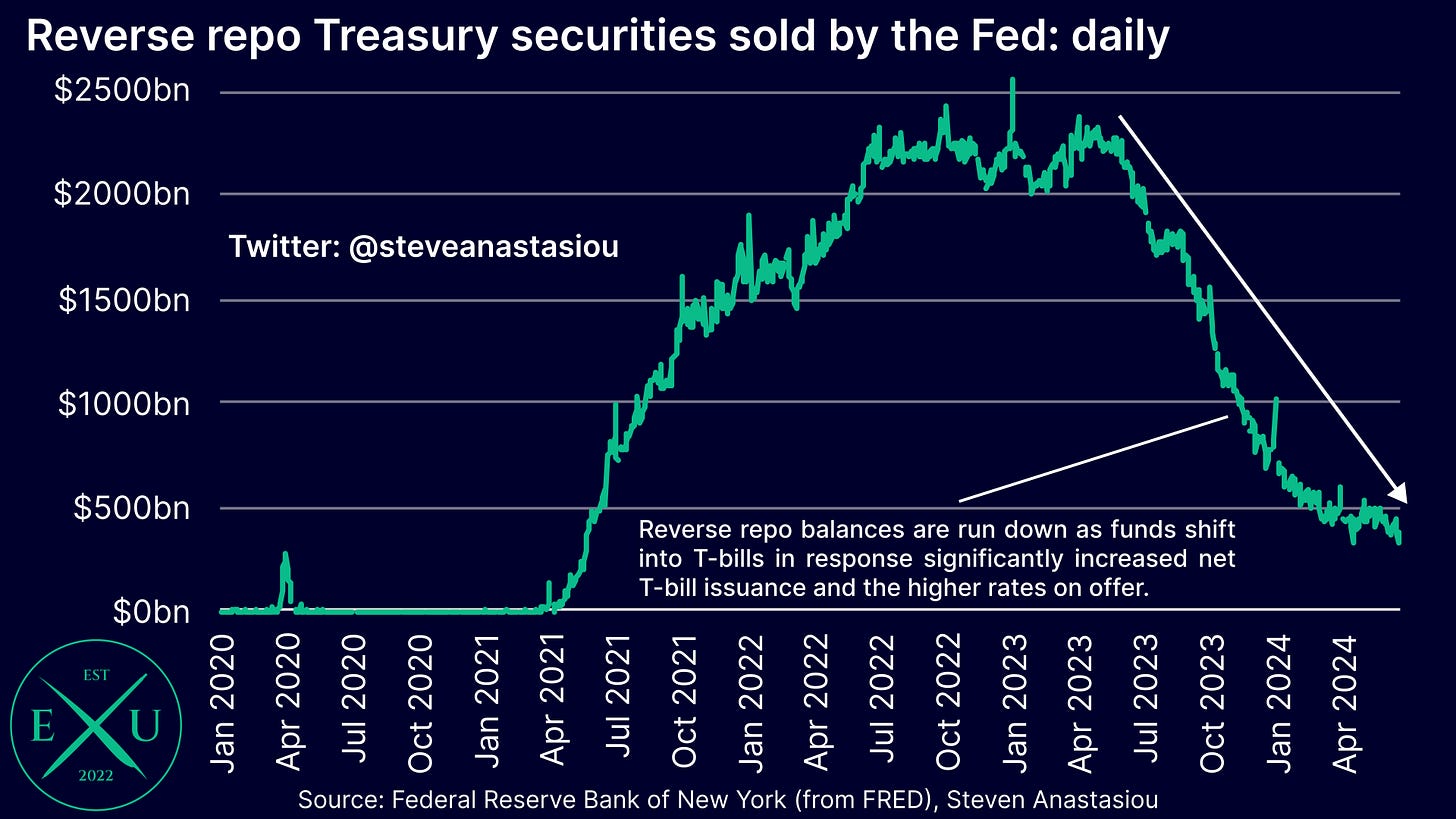

As a brief overview, the Fed’s RRP facility is used to mop up excess liquidity and prevent interest rates from falling below the Fed’s target range. Balances sitting within the Fed’s RRP facility can be thought of as consisting of “idle/inert” funds.

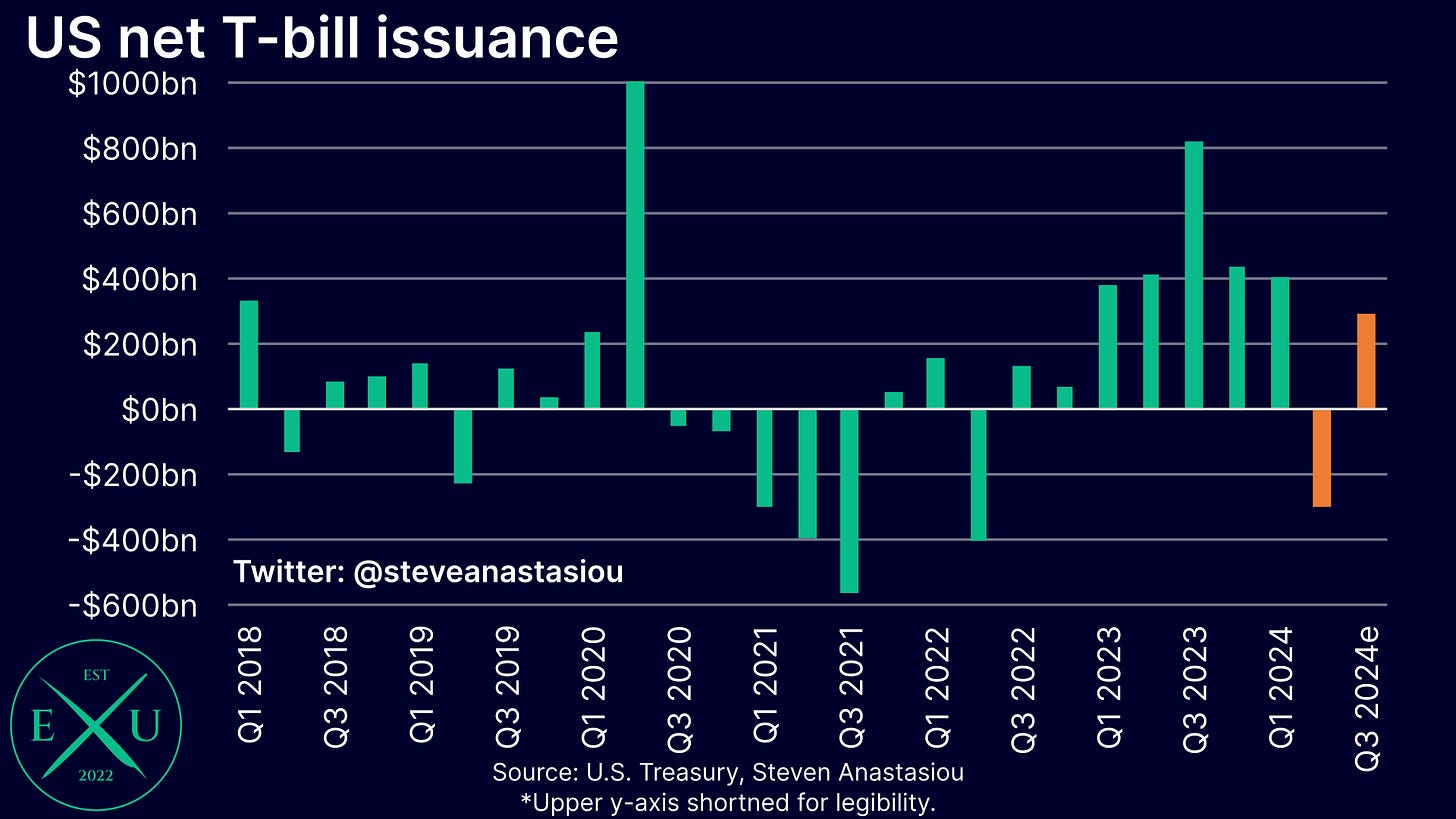

In the wake of the huge influx of post-COVID stimulus that was delivered, factors including a temporary but major decline in net T-bill issuance, acted to drive trillions of dollars into the Fed’s RRP facility, much of which stems from money market fund (MMF) investments.

Though with T-bills generally offering higher returns than the Fed’s RRP facility and a continued large federal government deficit leading to net T-bill issuance surging from 1Q23, MMFs have significantly reallocated into T-bills, with the RRP facility declining by trillions of dollars over the past year.

When funds are reallocated from the Fed’s RRP facility into T-bills, to the extent that the federal government spends the money received from increased net issuance (as opposed to simply using it to build its Treasury General Account (TGA)), this stimulates the economy by injecting otherwise idle funds into the real economy, boosting bank deposits. It is therefore no coincidence that the decline in bank deposits reversed and M2 stabilised, when the RRP facility began to drain significantly. This acted to break the link between the Fed’s QT and bank deposits (recall the chart posted above).

Another consequence of lower RRP balances, is that it can result in an increase in bank reserves — note how the beginning of the significant decline in RRP balances correlates to the rate of decline in bank reserves beginning to moderate and eventually turning YoY positive.

The support to bank deposits and liquidity provided by the draining of the RRP facility amidst a large federal government deficit, are likely key reasons for why the US economy has been more resilient than most expected over the past year, and for why asset prices like equities have continued to record strong price growth.