Shelter and the CPI: everything you need to know

How does the CPI calculate rents? Why does it lag? How big is the lag? How much does this impact the overall CPI? Read on to find the answers to all of these questions and more!

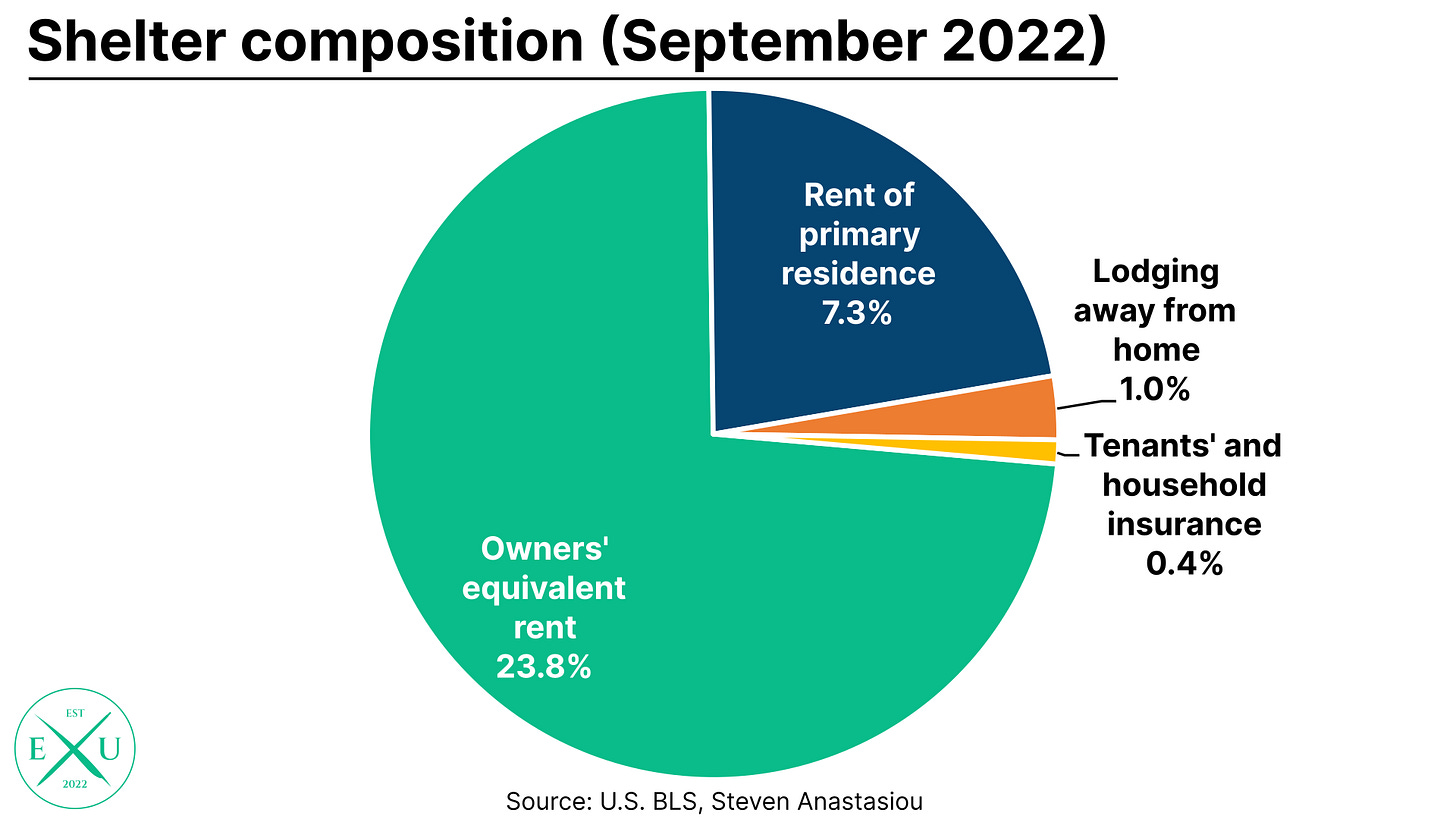

What is included in the CPI’s shelter index?

The shelter index is composed of four separate line items, being: owners’ equivalent rent (OER); rent of primary residence; lodging away from home; and tenants’ and household insurance.

The shelter index was equivalent to over 32% of the total CPI in September.

The two most critical components of the shelter index by far are the OER (>23% CPI weighting) and rent of primary residence (>7% CPI weighting) components. Given that they are easily the two most crucial components of the shelter index, this article will focus on OER and the rent of primary residence items.

How is OER and rent of primary residence calculated?

In order to calculate these two components, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) collects the rents paid on a sample of homes in a specific area. Each area is broken up into 6 separate panels, with the BLS collecting rent data from a given panel every 6 months. Rents for panel 1 will be collected in January, panel 2 in February and so on, with panel 1 resampled again in July. This means that the BLS collects updated rental data every month, but each specific housing unit is sampled every 6 months.

Note here how the BLS only collects rental data. While this is directly attributable to the rent of primary residence index, this is not the case for the OER index. This is why the index for people that have purchased their home is known as owners’ equivalent rent, as the actual cost of purchasing a home isn’t measured by the BLS. Instead, the cost of the service that a home provides, being shelter, is inferred by the rents charged on comparable homes.

Why does this methodology result in a lag to spot market rents?

The main point of concern raised with the BLS’ measurement of rents, and one in which I share and often point out, is that it results in a lag between actual spot market rents.