Lending data highlights the significant impact of the Fed's tightening

Historically a lagging indicator, aggressive Fed tightening has already resulted in a major decline in bank lending growth, indicating that the Fed does not need to hike rates further.

Executive summary

Lending data shows that the Fed’s tightening has had a major impact

While debate continues as to whether the Fed will, or should, deliver any further interest rate hikes, commercial bank lending data shows that the Fed’s tightening has already had a major impact.

The overall level of commercial bank loans & leases have been largely stagnant since February, marking a major shift from the significant growth seen in 2H21 and 2022. As a result, YoY growth has fallen from a peak of 12.4% in December 2022, to 4.4% as of 13 September, while 6-month annualised growth is just 0.6%.

Commercial & industrial and consumer automobile loans see a particularly significant hit, but commercial real estate loans continue to grow

Breaking down commercial bank loan & lease data into its key segments, shows that the outstanding amount of commercial & industrial loans has fallen by $70bn since peaking in February. As a result, YoY growth has plunged from 15.4% in November 2022, to just 0.2% as of 13 September. Historically, YoY declines in commercial & industrial loans are generally not seen without a recession having occurred.

Meanwhile, the outstanding amount of consumer automobile loans are contracting sharply, with YoY growth -2.2% and more recent trends even weaker: 6-month annualised growth is -4.7% and 3-month annualised growth is -7.2%.

While there continues to be significant concern around the outlook for commercial real estate debt (stemming from particular concerns around office real estate), banks are continuing to lend to the sector, albeit at a much reduced pace — YoY growth has fallen from 13.4% in March, to 7.2% as of 13 September. 3-month annualised growth of 3.0% points to a significant further moderation of YoY growth over the months ahead.

Rates have risen far enough to contain inflation — a continued tightening bias unnecessarily adds to the risk of a recession

With a reduction in lending growth a key factor by which higher interest rates work to slow economic growth and inflation, the major fall in bank lending growth provides a clear signal that further increases in interest rates are not necessary to contain inflation.

This argument is further supported by the fact that loan & lease growth is typically a lagging indicator, with YoY growth usually not seeing a large decline until a recession has already occurred. The typically lagging nature of lending, in conjunction with the rise in real rates as inflation has fallen, and the recent material increase in Treasury yields, all point to further downward pressure on lending growth over the months ahead, without any additional tightening from the Fed.

Furthermore, the ongoing continuation of QT, which acts to reduce the M2 money supply via its mechanical reduction of bank deposits and the flow-on effect to commercial bank security holdings, will act to further contain inflation over the medium-term, reducing the need for the Fed to further constrain bank lending to lower inflation. While its exact impact can’t be quantified, the impact that the Fed’s QT has on raising Treasury yields, also acts to increase loan rates without any further interest rate hikes from the Fed.

All-in-all, with widespread disinflation, a drastic decline in lending growth, and QT leading to declines in the M2 money supply, additional rate hikes from the Fed are not needed to contain inflation, and would unnecessarily add to the risk of a recession. This risk is particularly elevated on account of the fact that changes in the level of lending growth, and therefore the M2 money supply, tend to impact inflation and economic activity, with a significant lag.

Fed Chair Powell emphasised at his most recent FOMC meeting that now is the time to proceed “carefully” — given the significant tightening that the Fed has already delivered, a careful approach is the right one.

Though instead of a bias towards additional tightening and a higher for longer mantra, given the declines that have already been seen in lending growth and the M2 money supply, and the impact of these shifts being subject to long and variable lags, there’s a strong argument to be made that a careful approach would see the Fed shift its policy stance to a loosening bias — for in order to avoid a hard landing, a big ship’s course needs to be adjusted well in advance of the shore.

By continuing full steam ahead with its aggressive tightening, “higher for longer” risks becoming the new “transitory inflation”.

How Fed tightening impacts economic activity & inflation

In its quest to reduce inflation, the Fed has implemented two key monetary policy measures, being 1) higher interest rates; and 2) quantitative tightening (QT).

Focusing in on the interest rate channel, the key way in which higher rates work to reduce nominal economic activity and inflation, is by making borrowing more expensive, which discourages borrowing and encourages saving.

In light of the major increases in interest rates that have been seen, the Fed’s Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey (SLOOS) report has indeed shown that banks have seen a major reduction in loan demand over the past year.

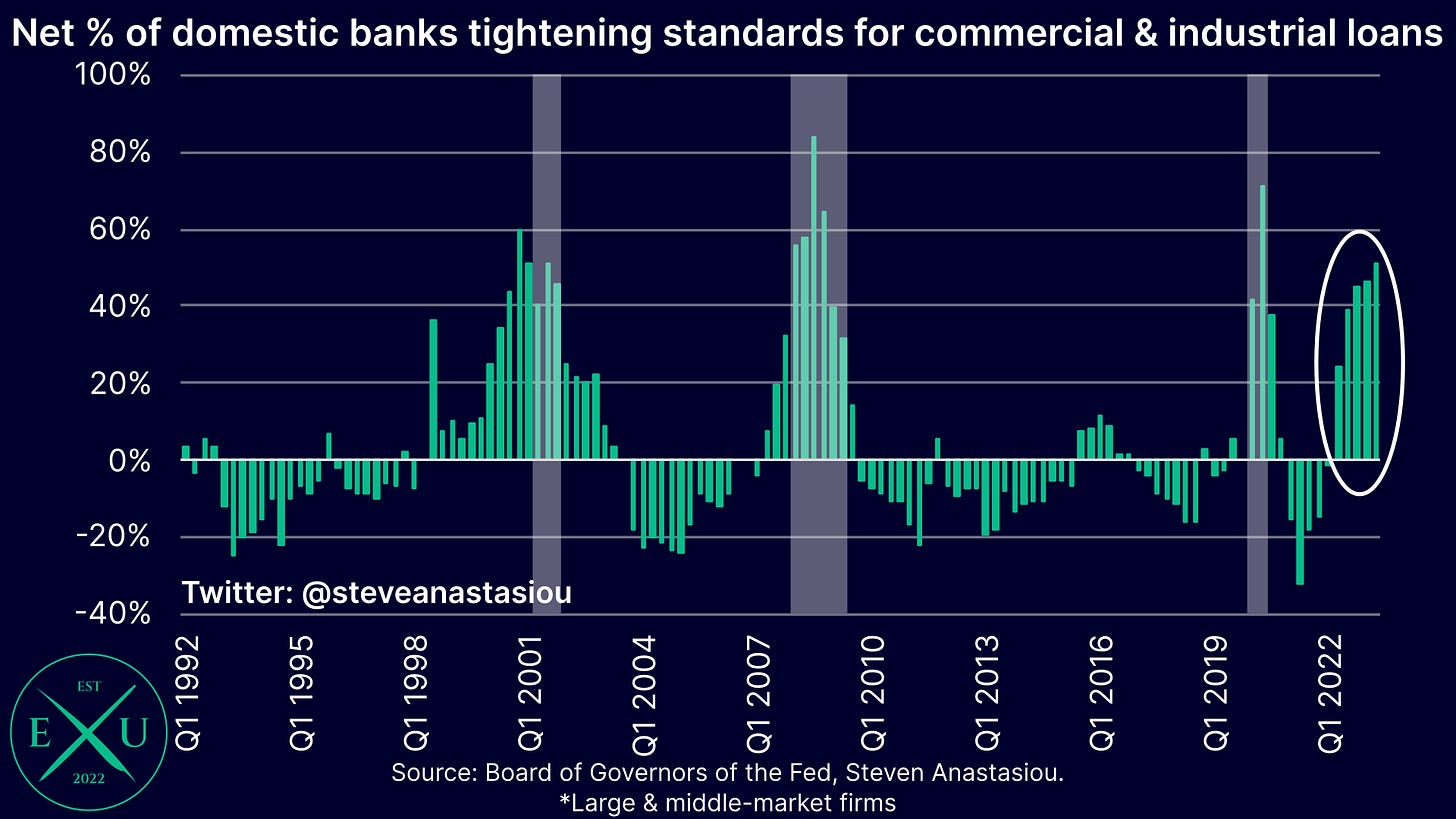

Higher rates can also lead to banking institutions tightening their lending standards, as they grow more worried about the economic outlook and the ability of their clients to meet repayments. This acts to further reduce the level of lending that takes place in an economy.

In addition to a reduction in loan demand, SLOOS data also shows that banks have significantly tightened their lending standards since Q2 2022.

By discouraging borrowing, less new credit will be issued, which in isolation, reduces the rate of growth in the money supply, which has a flow-on impact for nominal aggregate demand.

In the event that the outstanding level of loans and leases in the economy falls, in isolation, this will result in the destruction of money, promoting declines in nominal economic activity, and price deflation.

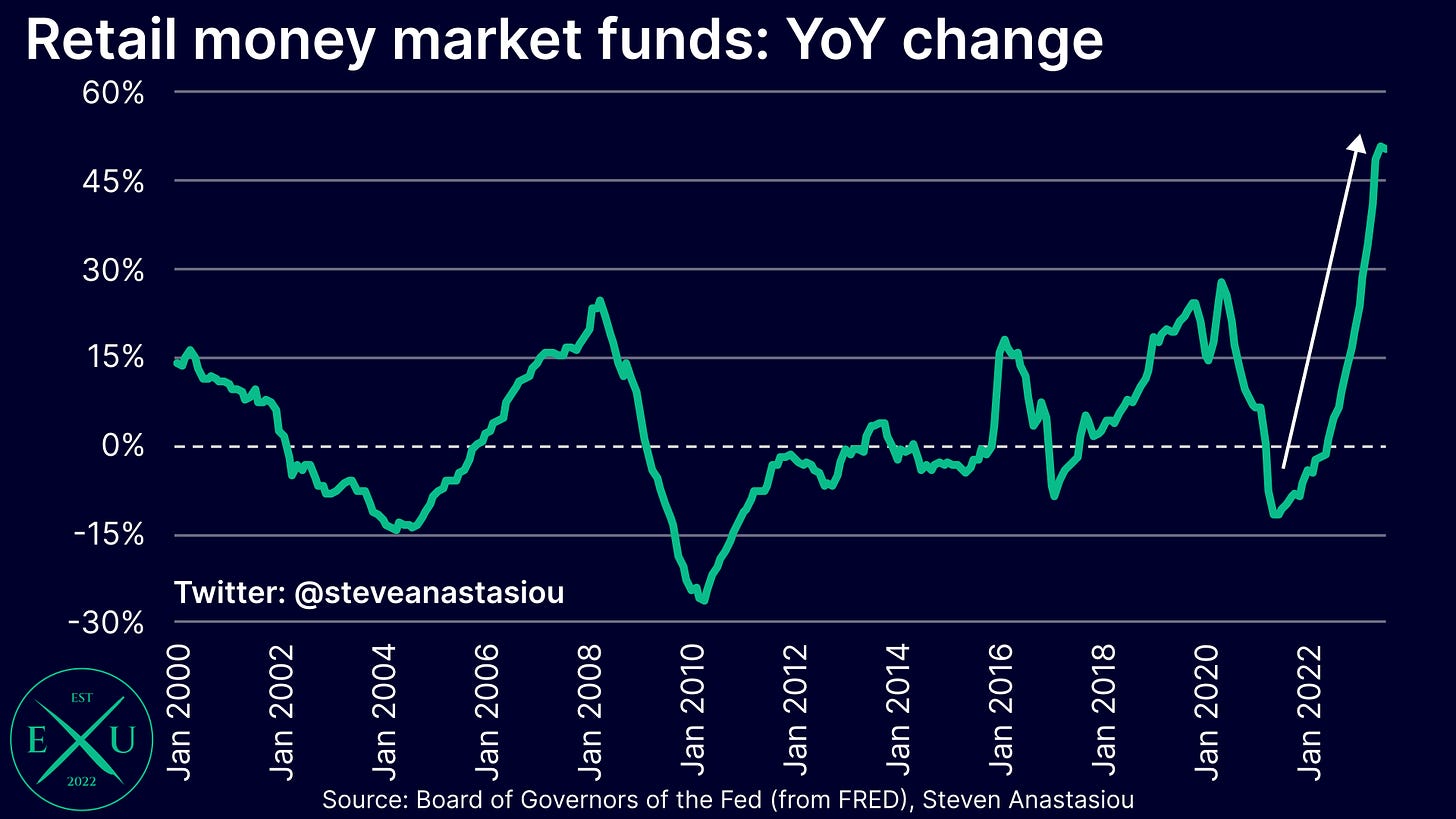

Meanwhile, increases in interest rates also act to reduce inflation by increasing the demand for money (savings), versus goods and services. We can see the impact of this preference shift playing out via the increases that have been seen in funds held in money market funds and time deposits, which bear a higher rate of interest.

Loan & lease levels have been largely stagnant since February

Given the impact of the Fed’s aggressive monetary policy tightening on loan demand and lending standards, the overall level of commercial bank loans & leases has been largely stagnant since February.

This is a major shift from the significant growth that was seen from 2H21 and throughout 2022, highlighting the major impact of the Fed’s policy actions.

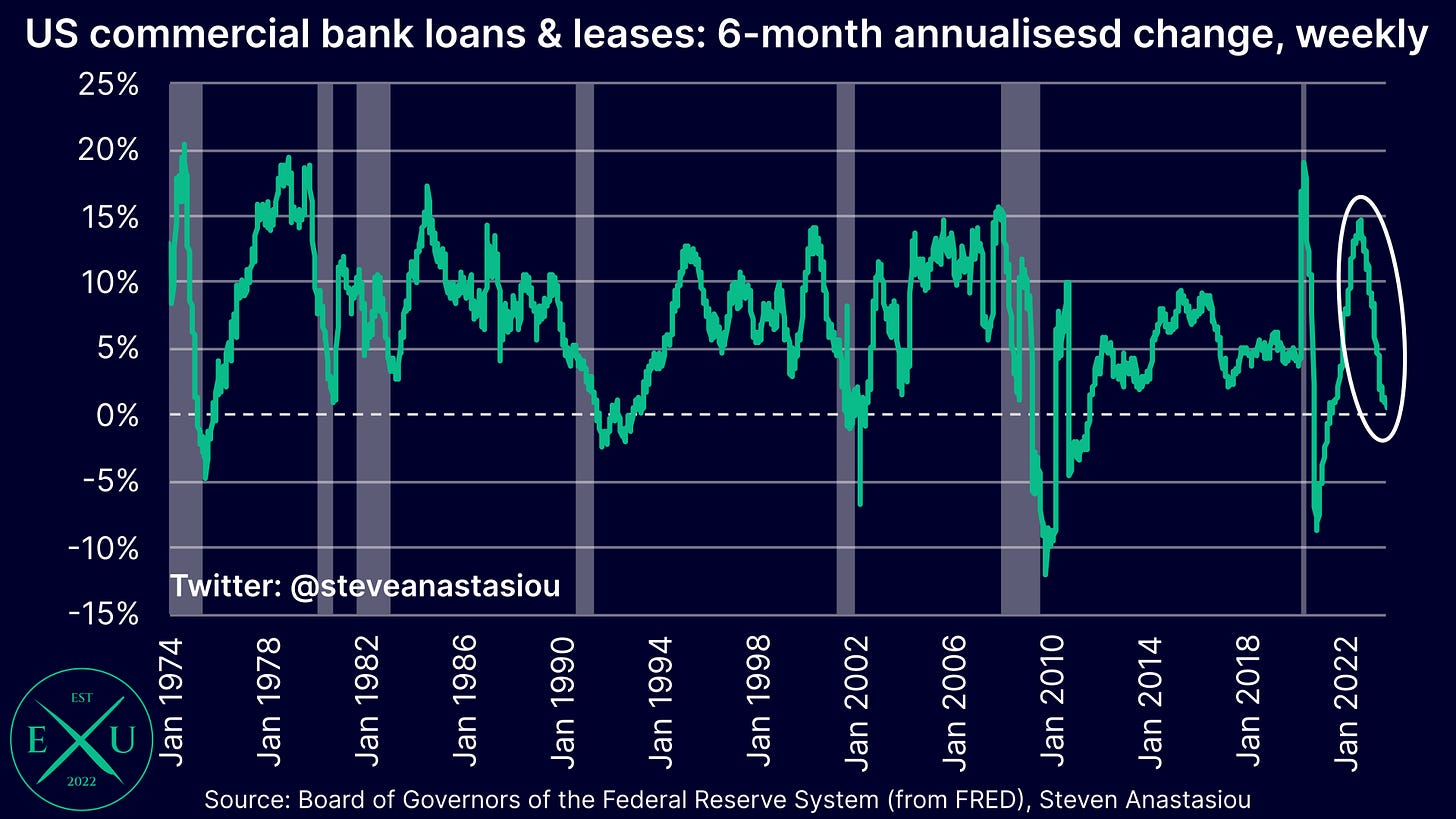

Decline in loan & lease growth has been well in advance of what is typically seen — further highlighting the significance of the Fed’s current tightening

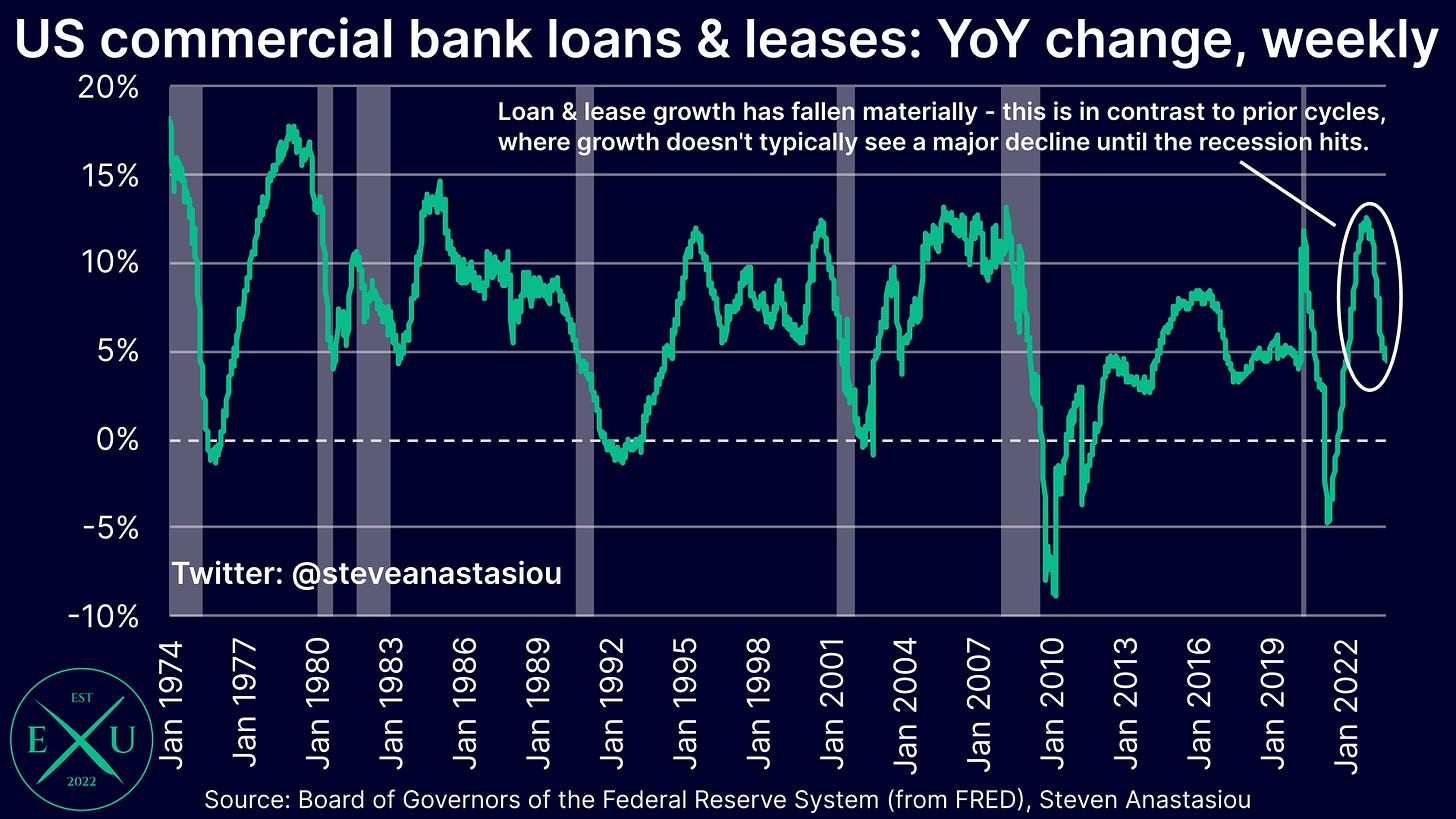

As a result of the relative stagnation in the outstanding level of loans and leases, YoY growth has fallen from over 12.5% in December 2022, to 4.4% as of 13 September.

Historically, loan & lease growth has typically been a lagging indicator, with a material moderation in YoY growth generally not taking place until a recession has already started, and not reaching a trough until after a recession has already ended.

The huge moderation in loan growth is thus coming at an earlier stage of the economic cycle than would typically be seen, again pointing to the significance of the Fed’s current tightening cycle.

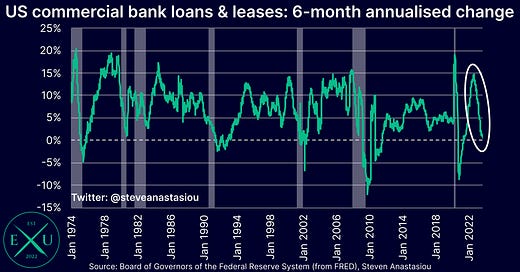

Given that the relative stagnation in loan & lease growth began in February, the decline in growth is even starker on 6-month annualised basis, where growth has fallen to just 0.6%, from a peak of 14.7% in August 2022.

Loan & lease trends by key segment

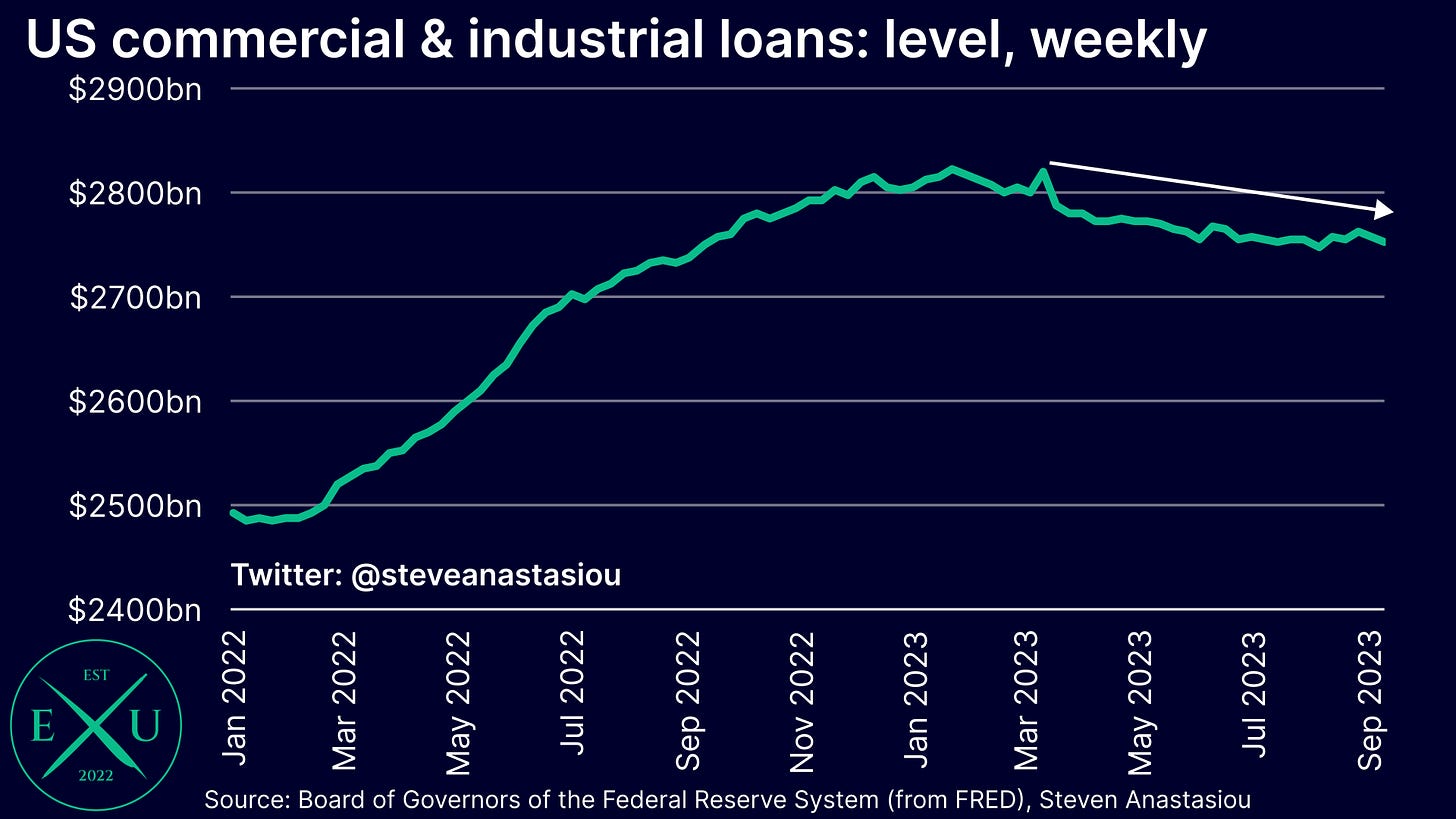

Commercial & industrial loans peak in February, on the verge of turning YoY negative

Since peaking in January, the outstanding level of commercial & industrial loans has fallen by $70bn. The decline began in earnest post the failure of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) in March, and continued until June. Since then, the overall level of commercial & industrial loans has largely flatlined.

This has seen YoY growth fall from a peak of 15.4% in November 2022, to just 0.2% as of 13 September. Excluding the abnormalities associated with the COVID period, a YoY decline in commercial & industrial loans has historically not been seen without a recession having occurred.

Despite concerns about commercial real estate, loans continue to be made — although the pace of growth has moderated significantly

The outstanding level of commercial real estate loans fell post SVB’s collapse, but soon thereafter, growth returned to an upward trajectory, and reached a new record in June.

In terms of the pace of increase, YoY growth has fallen from a peak of 13.4% in March, to 7.2% as of 13 September. On a shorter-term basis, 3-month annualised growth has fallen from an enormous increase of 18.4% in December 2022, to 3.0% as of 13 September, indicating that YoY growth is set to fall further over the months ahead. At 1.4%, growth is even weaker on a 6-month annualised basis, but this is directly comping the March high.

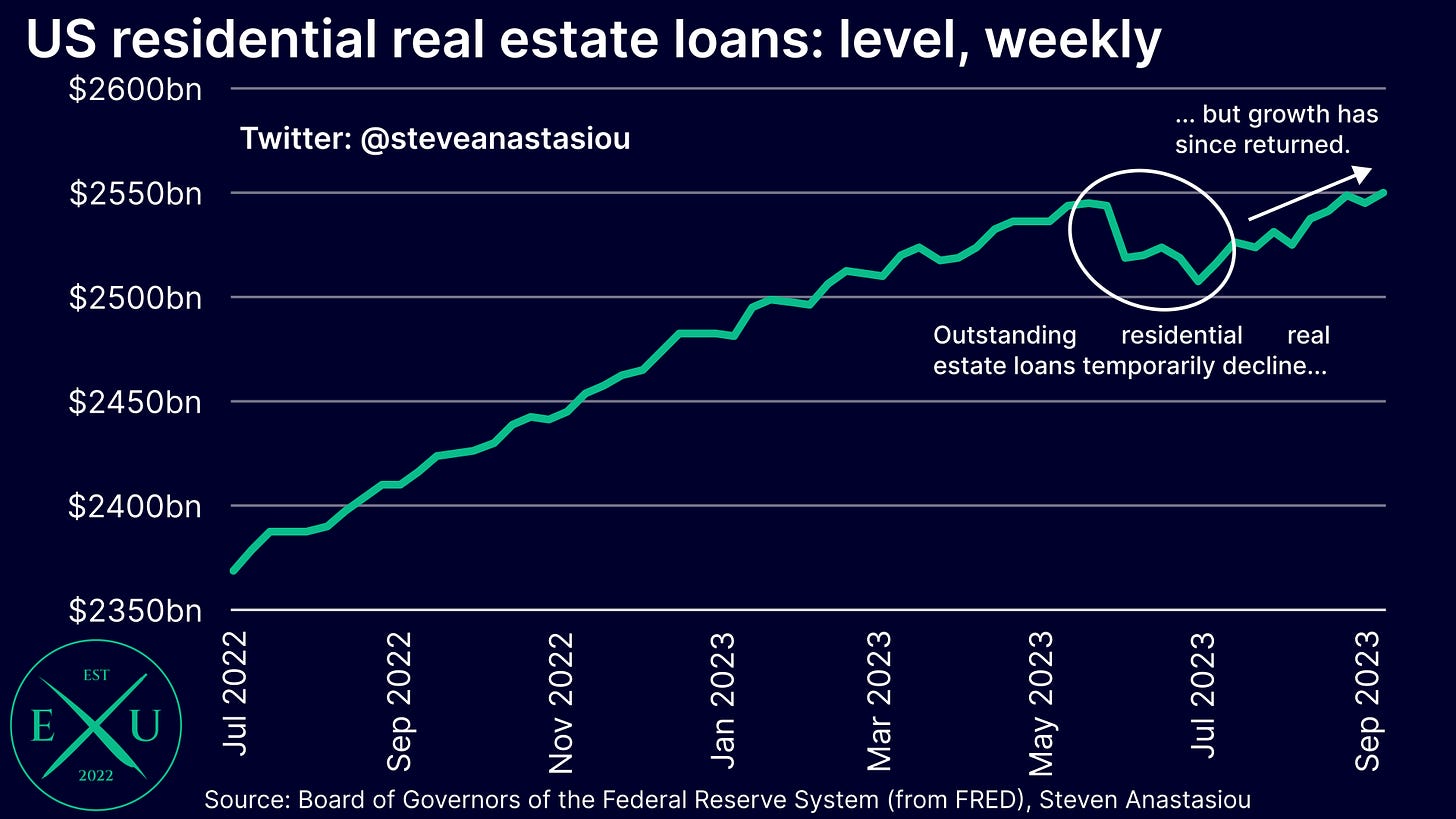

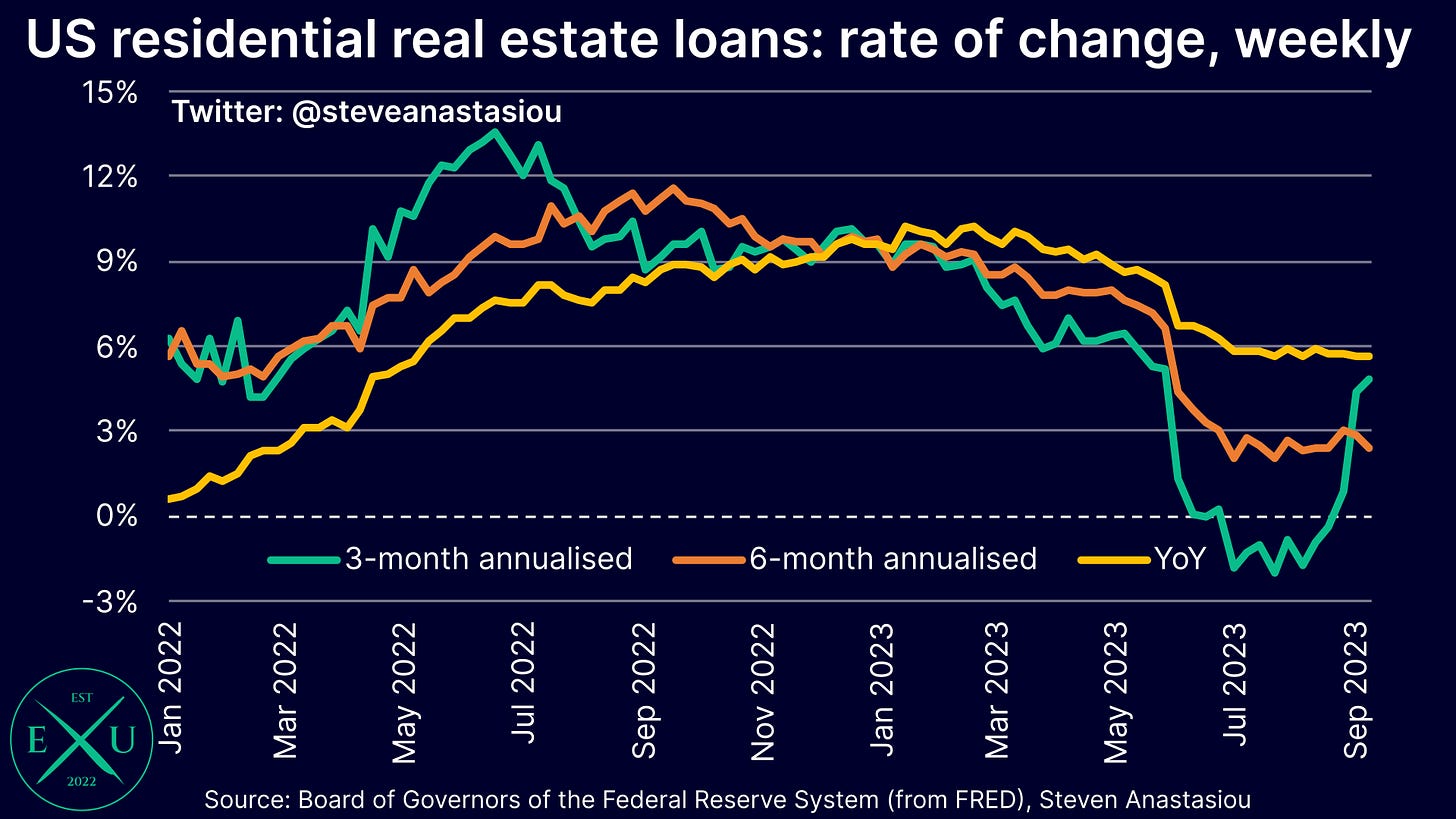

Residential real estate loans recover from a recent lull, but will growth fall away again as mortgage rates rise?

In contrast to commercial real estate loans, residential real estate loans did not see a significant decline post the collapse of SVB, and continued to trend higher until May.

At that point in time, there was a shift, with the total number of outstanding residential real estate loans falling by $36.7bn from their May peak to their July trough. More recently, growth has returned, with the total outstanding level of residential real estate loans reaching a new record at the end of August.

From a peak of 10.2% in January, YoY growth has fallen to 5.6% as of 13 September. Taking a more near-term view, after turning negative in July, 3-month annualised growth has rebounded to 4.9%, while 6-month annualised growth has fallen to 2.4%.

The key question moving forward, is that in light of the recent further jump in 30-year mortgage rates, will residential loan growth be material impacted? The most recent data points to a further slowdown.

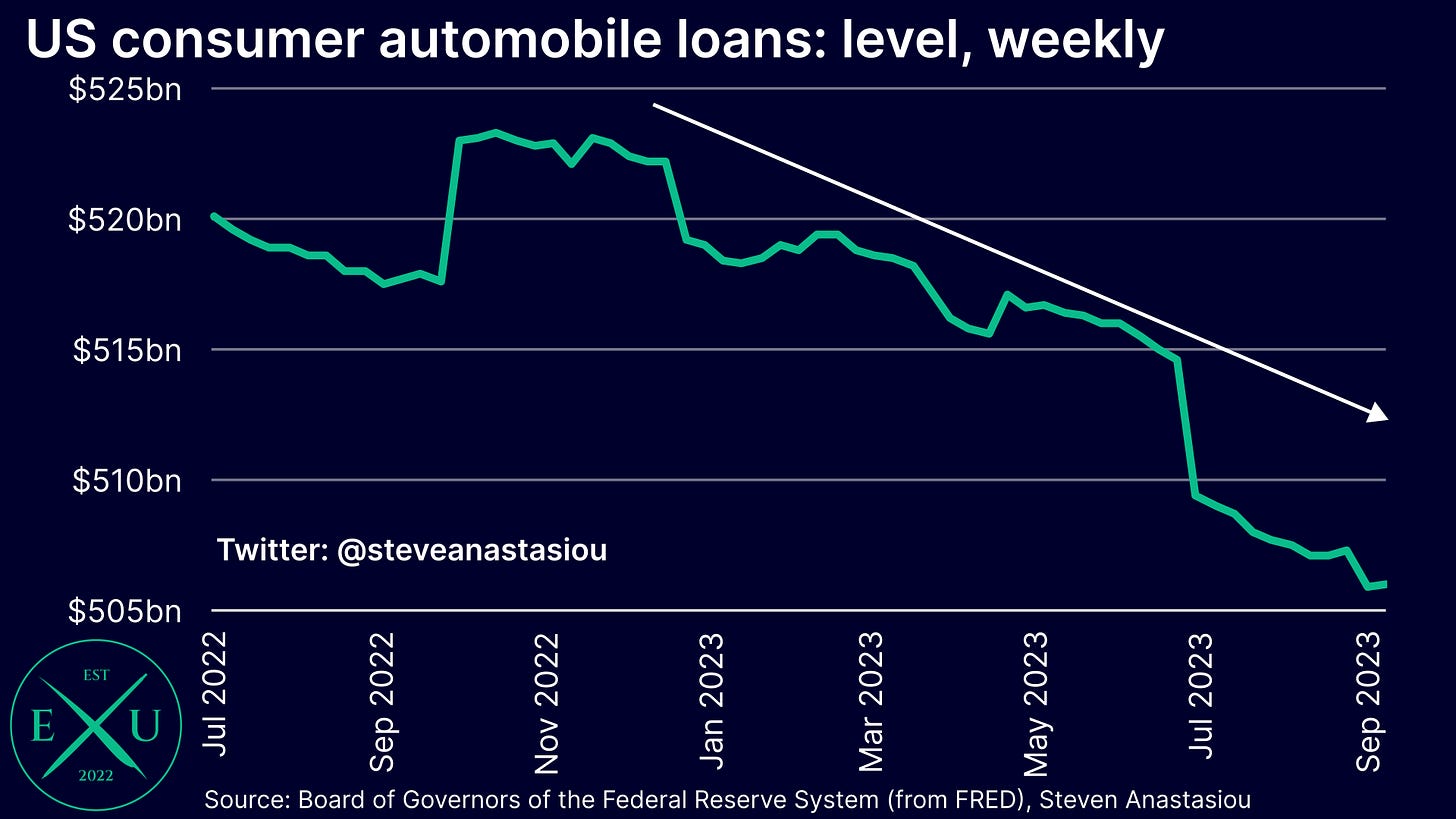

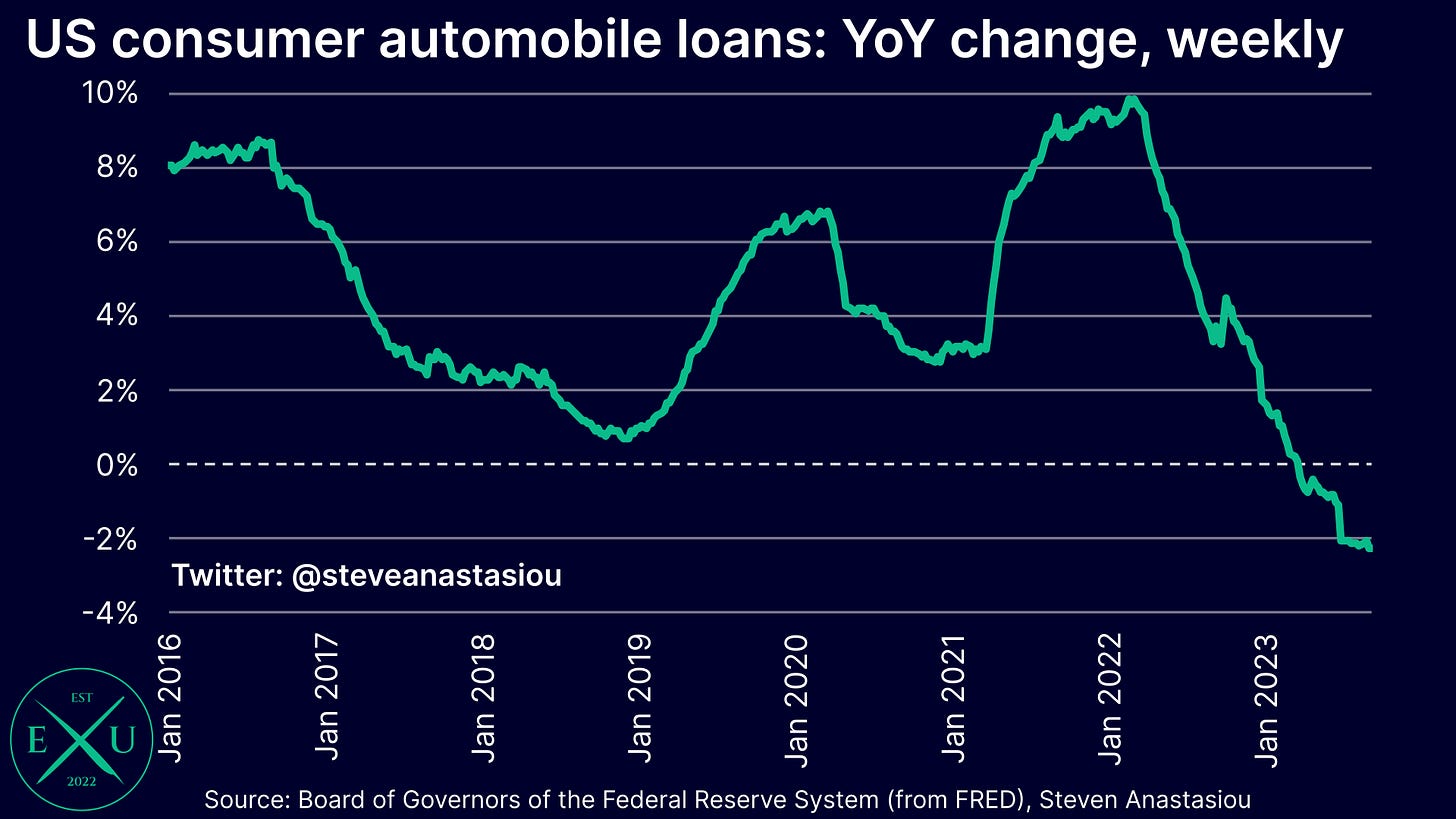

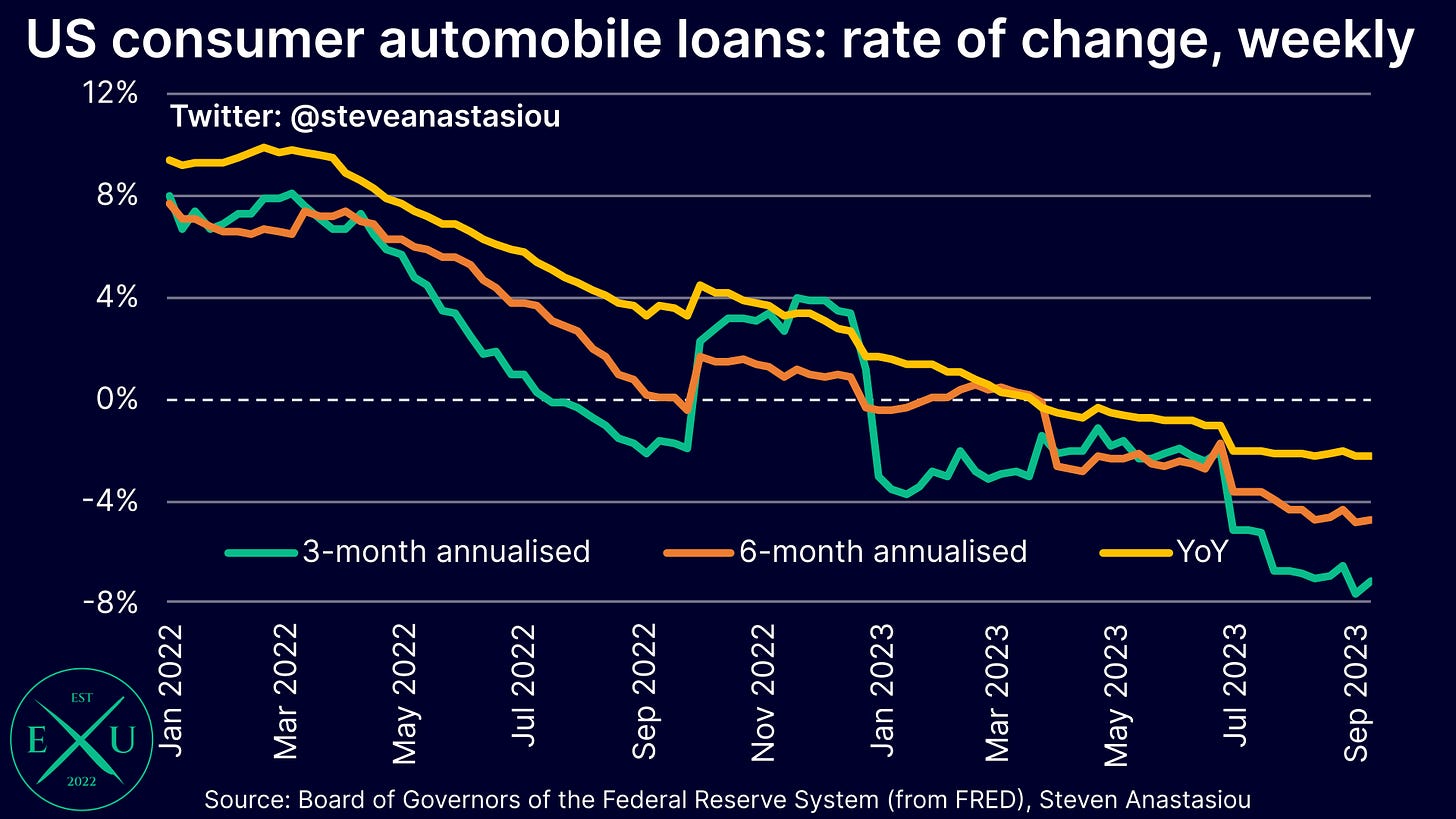

Automobile loans in decline as individuals respond to higher rates

Since peaking at $523.3bn in October 2022, the outstanding level of consumer automobile loans has fallen to $506.0bn, and continues to remain in a downtrend.

On a YoY basis, growth has fallen to -2.2%, which is the lowest level recorded for the data series, which dates back to 2016.

More recent trends show even weaker growth: 6-month annualised growth is -4.7% and 3-month annualised growth is -7.2%.

A variety of other consumer loans are also off peak levels

As is the case with automobile loans, the all other consumer loans category, which includes student loans, loans for medical expenses, vacations and other personal expenses, has also seen the total number of outstanding loans fall from peak levels.

Hitting a peak of $384.4bn in June, the outstanding amount of all other consumer loans was $377.1bn as of 13 September.

As a result of the decline in the total amount of all other consumer loans, YoY growth has fallen from a peak of 14.2% in April 2022, to 2.1% as of 13 September. While the above chart shows that the level of all other consumer loans has recently stabilised, the potential remains for YoY growth to turn negative by year’s end.

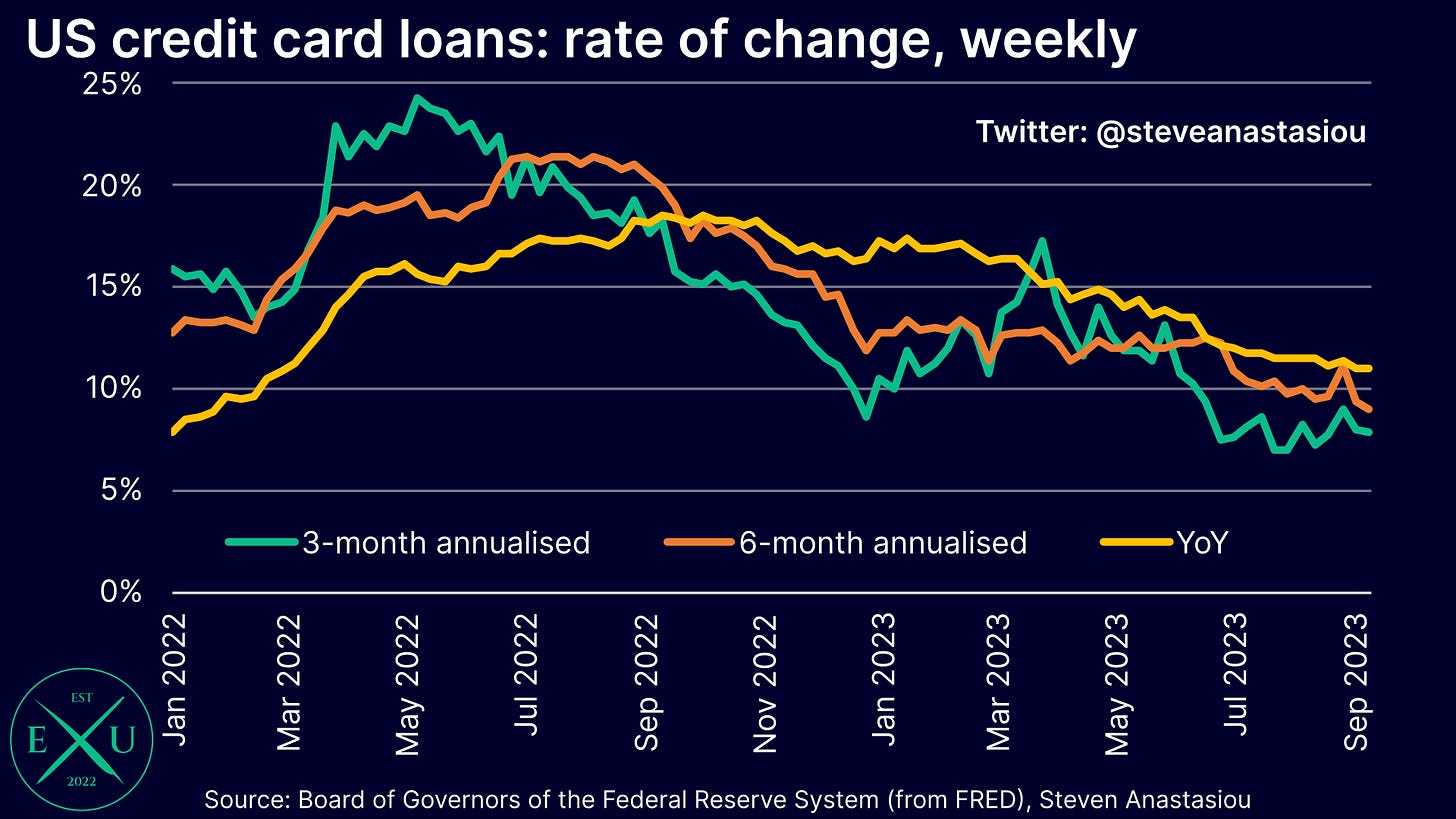

Individuals tapping into expensive debt as credit card loans continue to rise

While individuals are forgoing additional car loans, they continue to binge on credit card debt, which after seeing material repayments made in the wake of COVID stimulus being handed out, has continued to grow and grow since 2H21.

While off its October 2022 peak, when enormous YoY growth of 18.5% was recorded, at 11.0% as of 13 September, annual growth continues to remain high. While slightly softer, more recent growth rates also continue to remain elevated: 3-month annualised growth is 7.9%, while 6-month annualised growth is 9.0%.

The Fed has done enough to contain inflation, going further unnecessarily adds to the risk of a recession

Since peaking at 14.7% in August 2022, 6-month annualised commercial bank loan & lease growth has fallen to just 0.6%.

With a reduction in lending growth the primary manner by which higher interest rates work to slow economic growth and inflation (by reducing the rate of increase in the M2 money supply), the major reduction in bank lending growth provides a clear signal that further increases in interest rates are not necessary to contain inflation.

This is especially true in light of the Fed’s ongoing QT, which is contributing to a decline in bank deposits and commercial bank security holdings, which is resulting in outright declines in the M2 money supply, and thus negating the need for additional interest rate hikes to further temper lending growth.

Further supporting the case for no additional rate hikes from the Fed, is that lending growth is typically a lagging indicator, with growth tending to not materially fall until a recession has already begun. This again indicates the significance of the Fed’s tightening, and that further declines in lending growth may be yet to come (perhaps it also indicates that further negative economic data revisions may lie ahead).

The significant decline that has been seen in inflation over the past year and the return to significant positive real interest rates, as well as the recent further rise in Treasury yields, are additional factors that point towards a further reduction in lending growth over the months ahead.

All-in-all, with disinflation widespread, lending growth seeing a major decline, and ongoing QT leading to declines in the M2 money supply, any additional interest rate hikes from the Fed are not needed to contain inflation, and would unnecessarily add to the risk of a recession. This risk is particularly elevated on account of the fact that changes in lending and the M2 money supply, tend to impact inflation and economic activity with a significant lag.

Indeed, once all of these factors are considered in totality, instead of a resurgence in inflation, the bigger medium-term risk is that of a deflationary bust, meaning that as opposed to an additional tightening bias and a higher for longer mantra, the Fed should be looking to shift its policy stance towards a loosening bias — when long and variable lags are in play, one needs to adjust a large ship’s course well in advance of the shore, in order to avoid a hard landing.

By continuing full steam ahead with its aggressive tightening, “higher for longer” risks becoming the new “transitory inflation”.

To finish with one last point, some may note that the US economy managed to navigate a decline in loans & leases during 2020, and flat growth in 1H21, and thus could do so again. The key difference then, was that declining/flat loan growth was offset by the Fed’s enormous QE, which saw an enormous increase in the M2 money supply — this is very different to today’s environment, where the Fed’s aggressive tightening is resulting in the largest declines in the M2 money supply since the Great Depression.

Thank you for reading my latest research piece — I hope it provided you with significant value.

Should you have any questions, please feel free to leave them in the comments below!

In order to help support my independent economics research, please consider liking and sharing this post and spreading the word about Economics Uncovered. Your support is greatly appreciated and goes a long way to helping make Economics Uncovered a sustainable long-term venture that can continue to provide you with valuable economic insights for years to come.

If you haven’t already subscribed to Economics Uncovered, subscribe below so that you don’t miss an update.