Despite the CPI recording its seventh consecutive month of lower YoY growth, as I anticipated in my January CPI preview, the increase in the MoM rate of inflation has ignited debate as to whether the US is on the cusp of a renewed move higher in YoY CPI inflation.

After flagging my expectation for a higher than expected consensus headline CPI print (actual YoY: 6.4%, consensus: 6.2%, my forecast: 6.3%), is there anything in the latest inflation numbers that has led me to materially change my view, being that YoY CPI inflation is set to see a significant decline during 2023, and that instead, a material shift higher in YoY CPI inflation lies ahead? No.

Let’s first unpack some of the key details from January’s CPI report, after which I will explain my broader, bigger picture thought process on where inflation is headed.

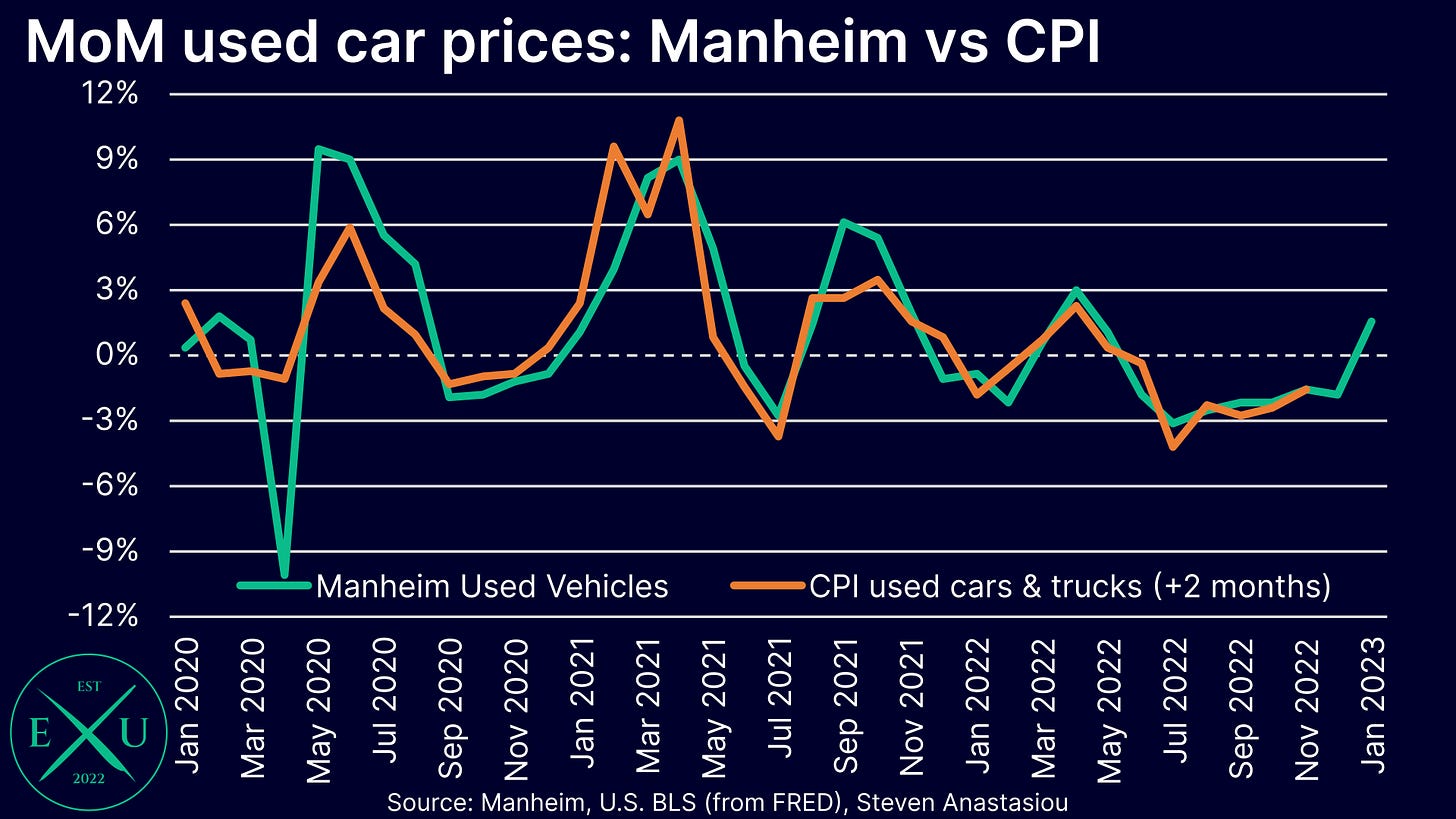

Used car prices fall again in January, as the CPI lags the Manheim index

As I articulated in my CPI preview, while some were concerned that increases in the Manheim Used Vehicle Value Index would see used car prices rise in January, there were two caveats to such a conclusion: 1) raw, non-seasonally adjusted Manheim data only increased in January, not December; and 2) the raw, non-seasonally adjusted CPI used cars & trucks index tends to lag the Manheim index by ~2 months.

This suggested that instead of seeing an increase in January, used car prices may rise in the CPI until March.

What actually occurred? MoM unadjusted CPI used car & truck prices declined by the same amount as the Manheim index did two months prior — 1.6%.

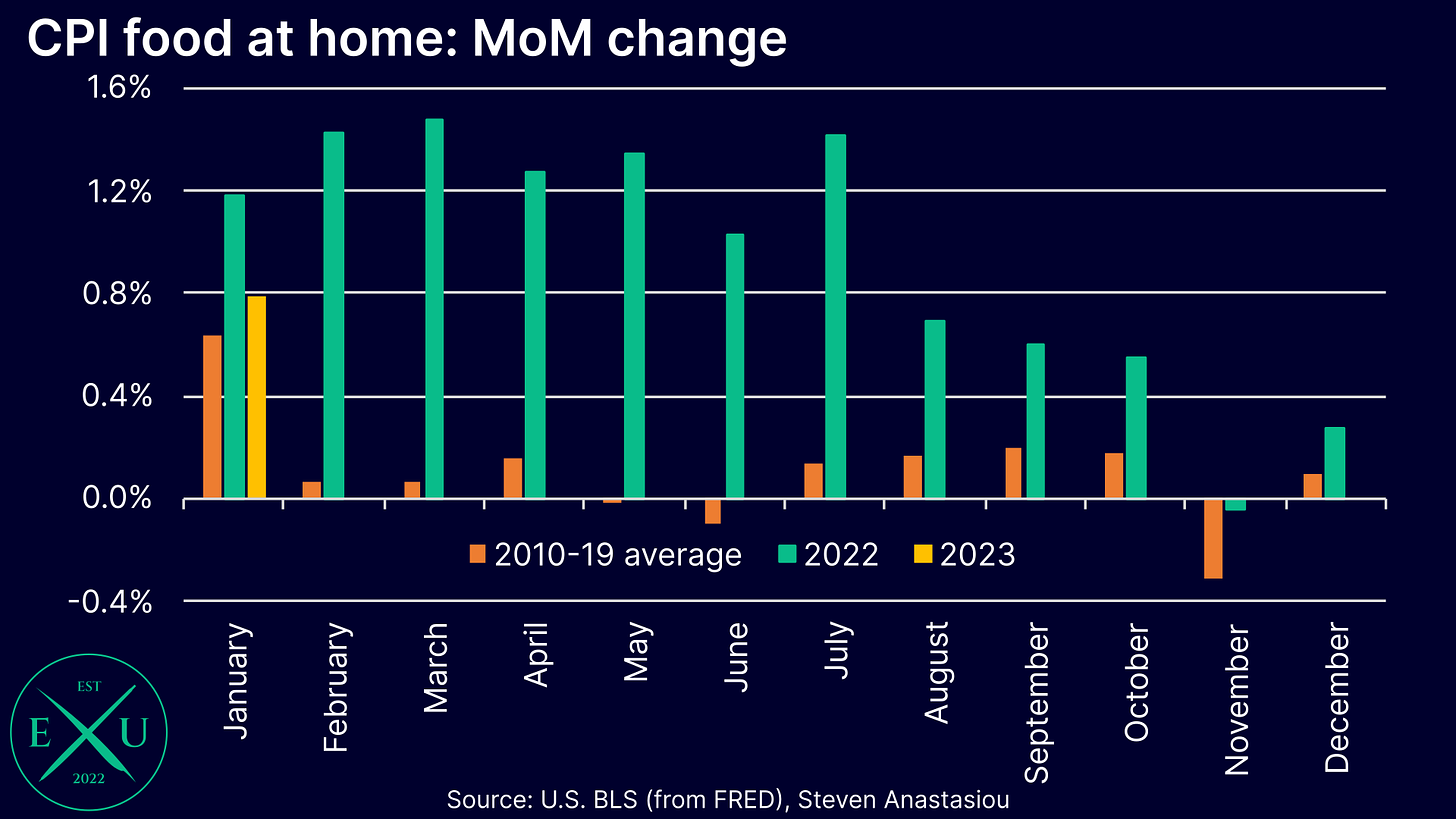

Food at home prices continue to decelerate, but food away from home moves the other way

As anticipated, food at home prices continued to decelerate in January (albeit only modestly versus December), moving slightly closer towards their historical average monthly change in January, and well below the prior year’s monthly increase.

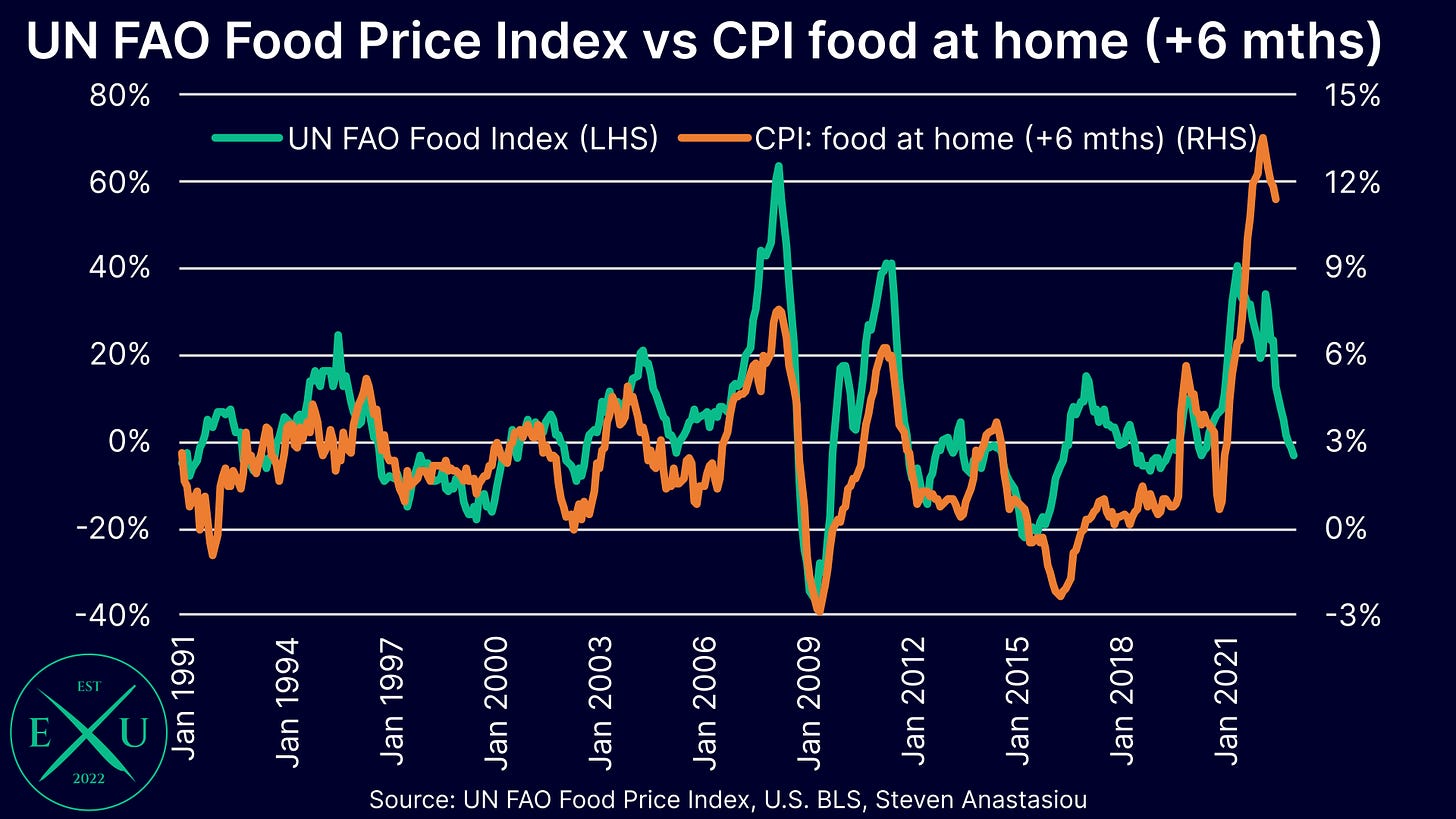

This further moderation coincides with the UN FAO Food Price Index having fallen for 10 consecutive months (to which the CPI food at home index is highly directionally correlated on a 6 month lag).

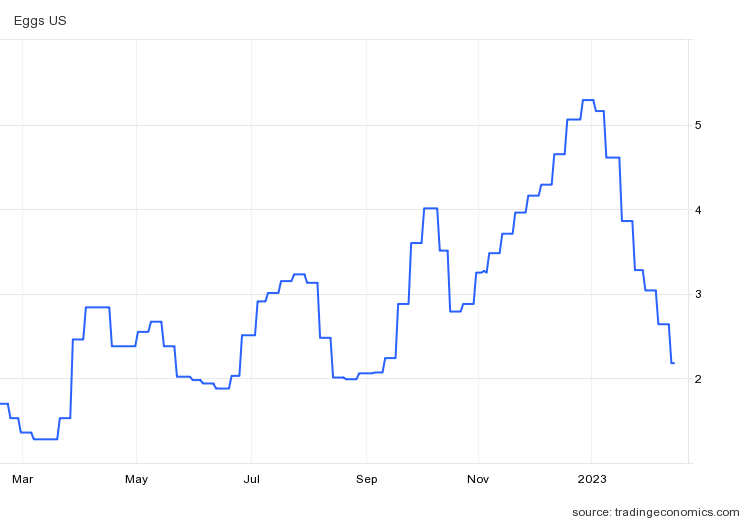

With wholesale egg prices collapsing since the beginning of the year, there should be further impetus for food at home price growth to moderate, with the 70.1% YoY increase in CPI egg prices set to unwind over the months ahead.

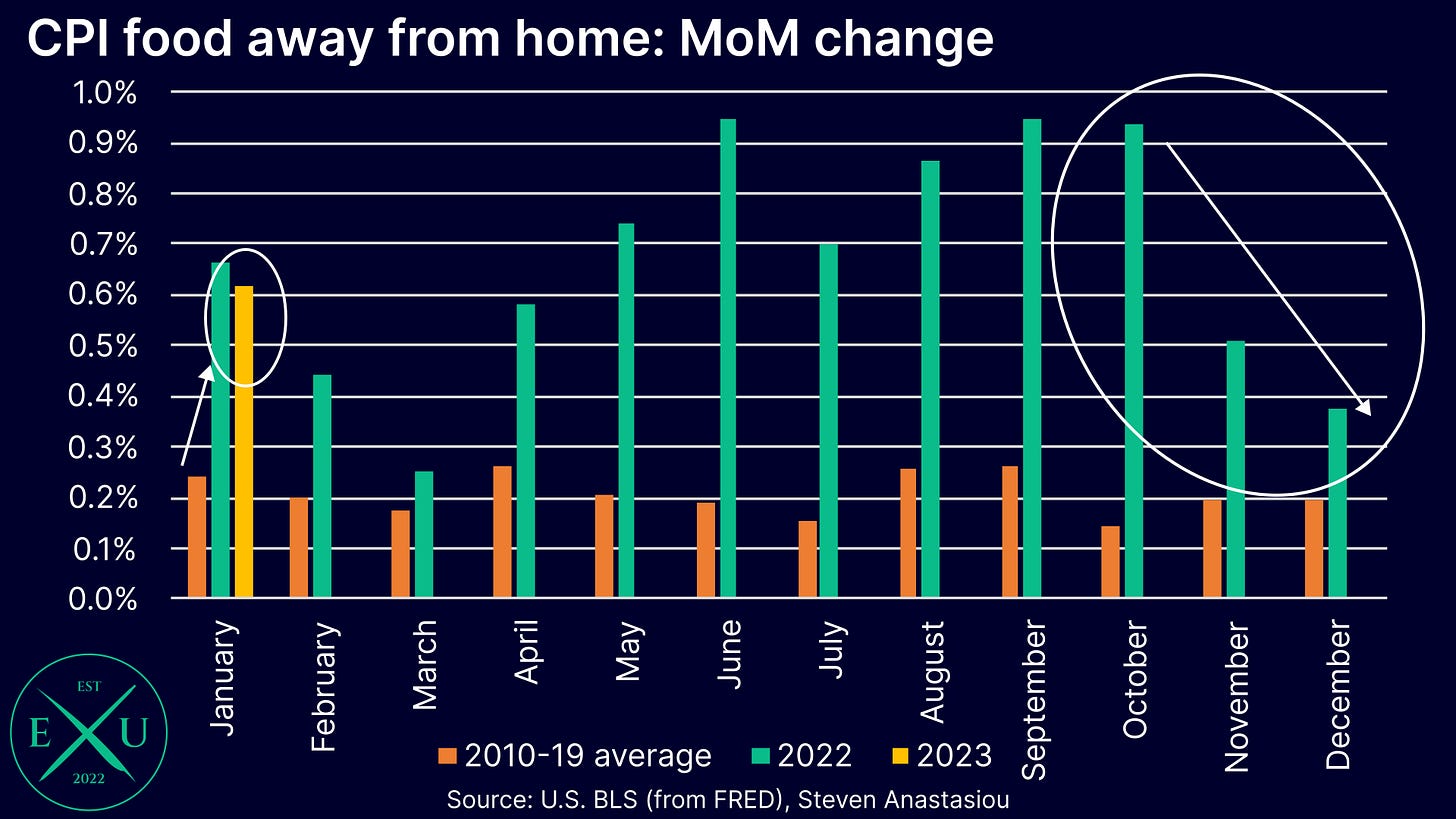

Moving in the other direction was food away from home prices, which after decelerating towards historical norms during the past two months, reaccelerated somewhat in January. Whether prices continue to reaccelerate, or MoM price growth moderates over the months ahead, will be an important indicator to monitor.

Rent based measures continue their fast growth, but moderate somewhat

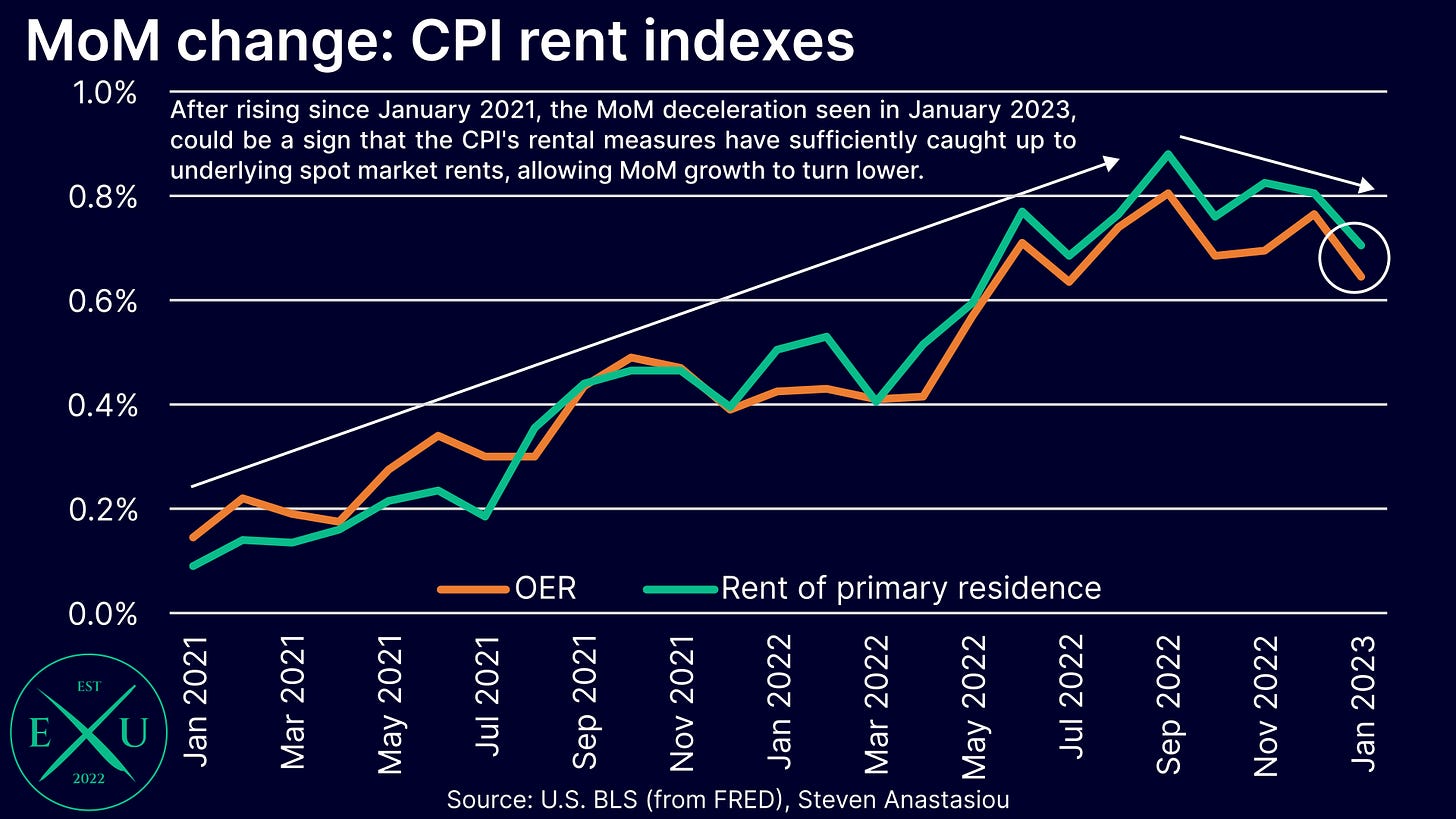

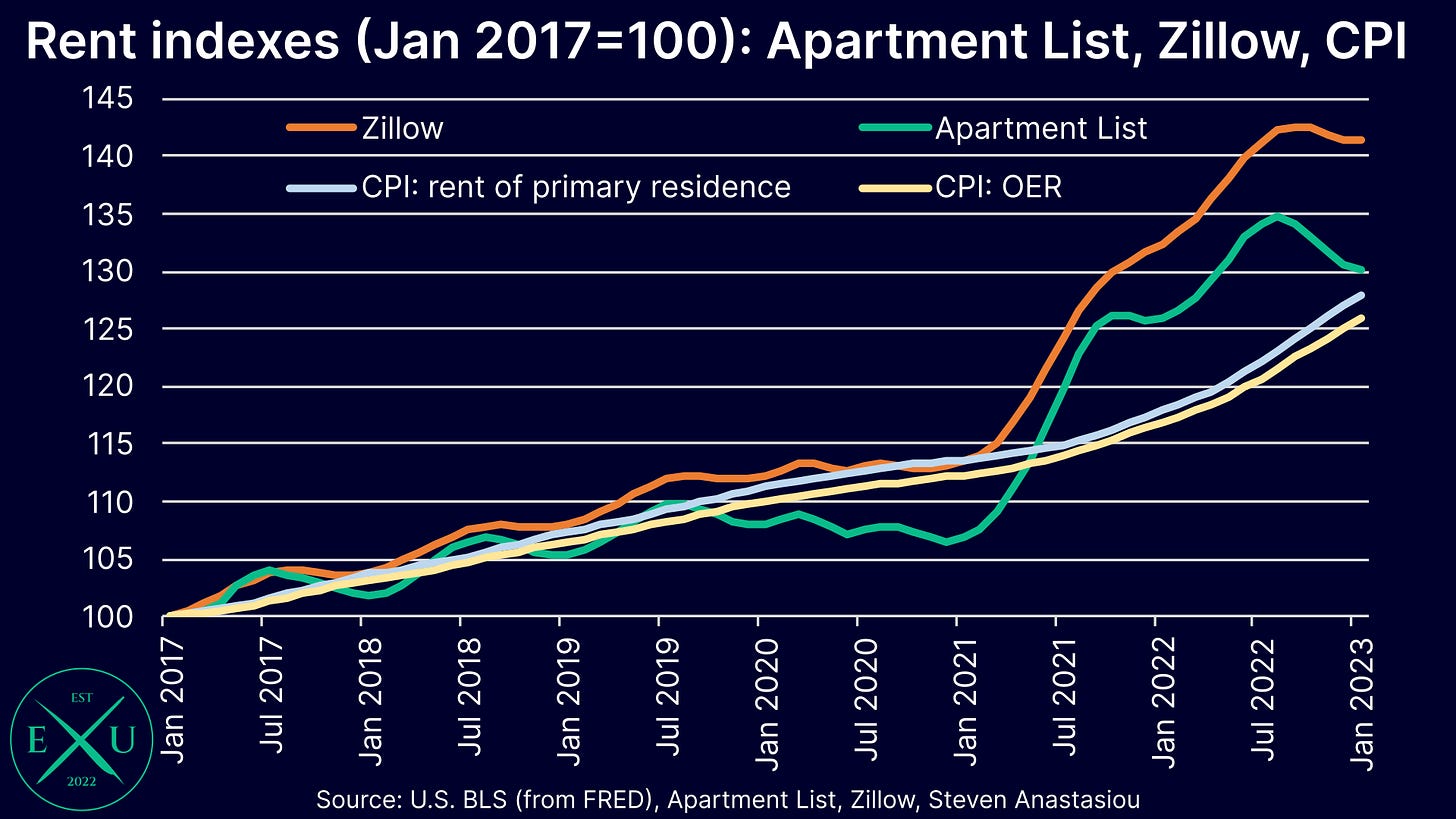

While still growing at a strong pace, the CPI’s rent based measures (owners’ equivalent rent (OER), and rent of primary residence) saw some moderation in their MoM growth rates in January.

With both OER and rent of primary residence converging significantly to spot market rental indexes over recent months, this could be a sign that the CPI’s rental based measures will now begin a period of deceleration. It will be important to see whether February’s numbers add further weight to the beginning of a deceleratory trend starting.

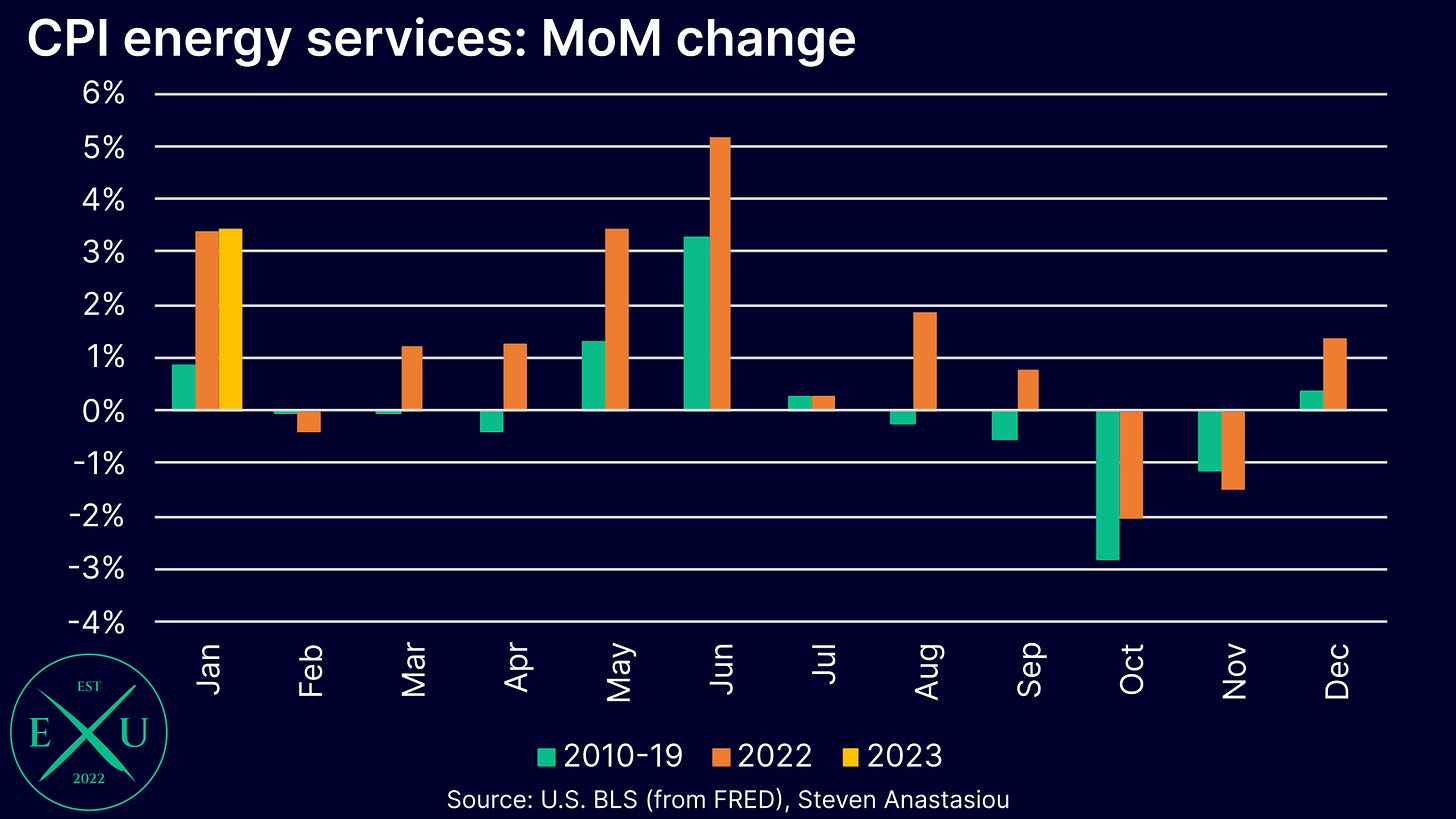

Energy services prices jump, despite lower natural gas & coal prices — expect this to normalise

Despite natural gas and coal prices plunging over recent months, CPI energy services prices rose significantly in January (as they also did this time last year). Unlike gasoline prices which have fallen materially from their peaks, electricity and utility gas prices have generally continued to rise at rates well above their historical averages throughout 2H22, and now into 2023. Nevertheless, given the backdrop of natural gas and coal prices that have continued to fall significantly over recent months, I would expect that energy services price growth begins to gradually normalise over the months ahead.

Some core services are continuing to show high price growth

After covering the key durables and nondurables components (as well as the energy services component, which is more impacted by nondurable commodity prices), it’s time to now turn our attention to services prices, where signs of continued significant price growth can be readily seen.

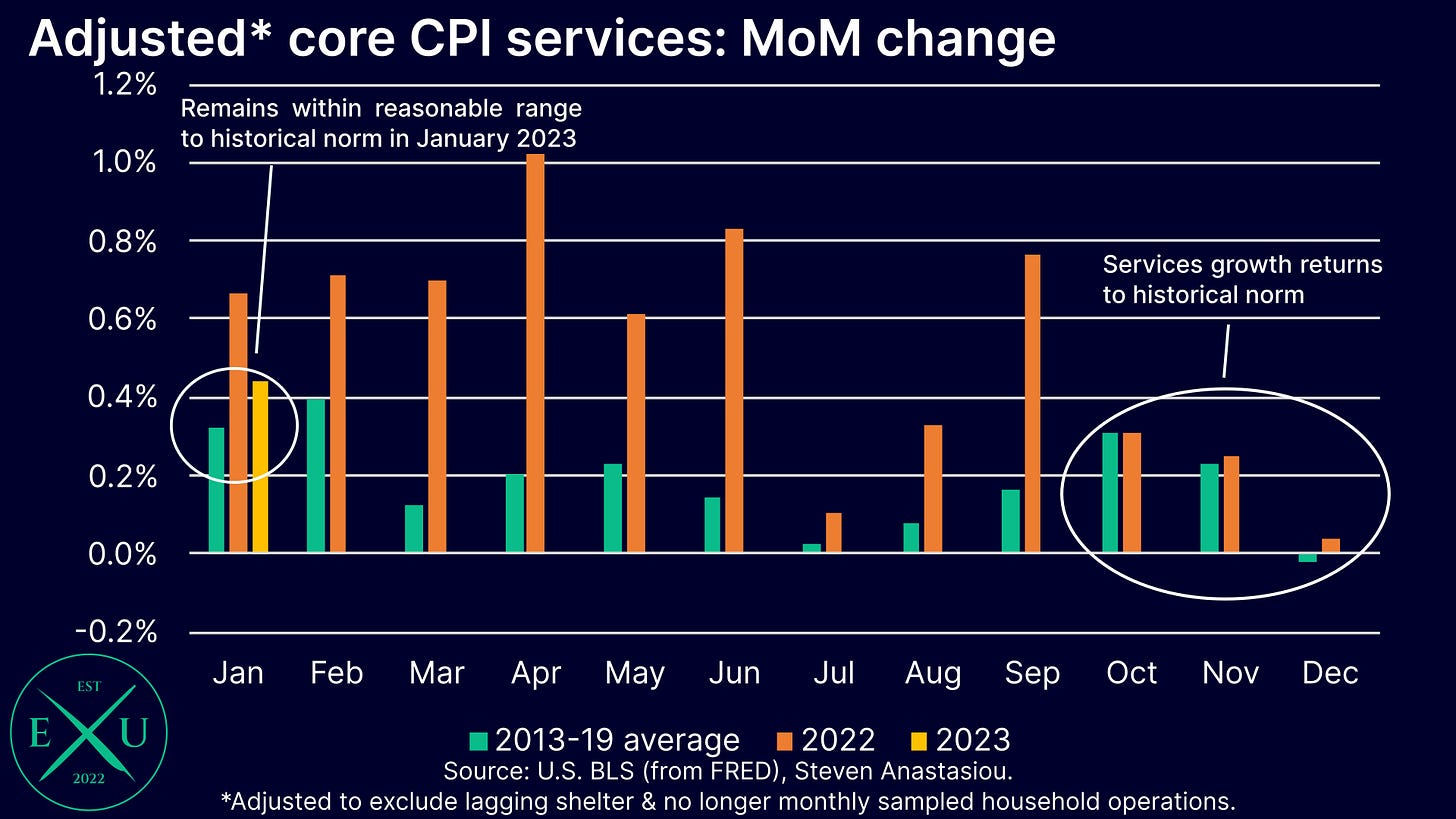

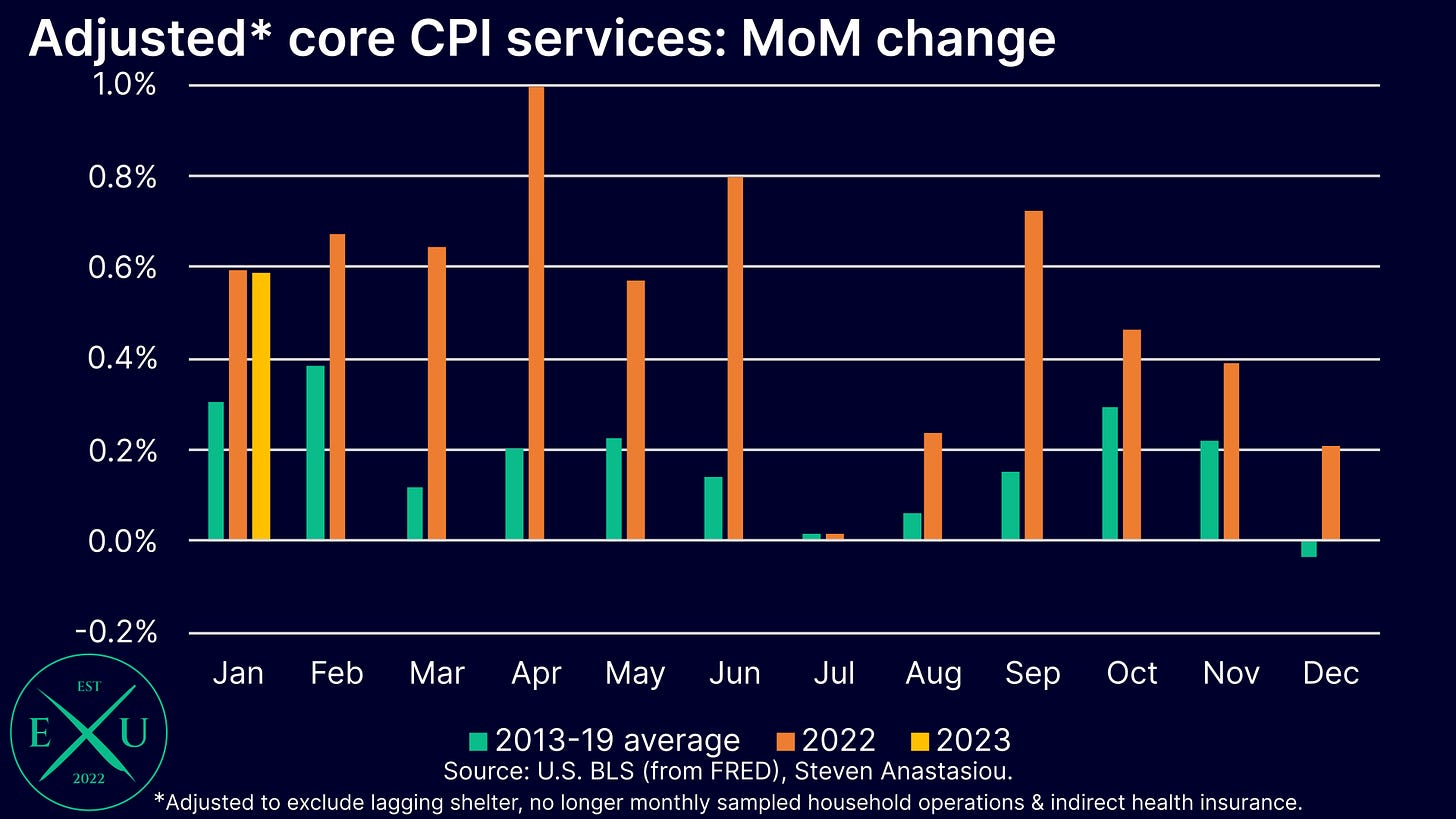

When analysing services prices, it’s important to exclude shelter costs, given that they are a lagging indicator, and we know that they will trend lower over time given the recent movements in spot market rents. Given that we have discussed energy services inflation, and how it’s more linked to commodity prices than typical services industry price pressures, it will also be excluded. Additionally, I have excluded household operations from the below numbers, as the BLS has stopped producing updated figures for this category — the last month recorded was in October 2022.

The remainder of the CPI services index, representing ~23% of the overall CPI, has seen a significant deceleration in monthly price growth since October 2022, to levels that are consistent with monthly average price changes from 2013-19 — which is at odds with commentary that core services price growth remains too high.

One might ask, what’s happened since October? A significant adjustment — a major shift in health insurance costs. The BLS annually estimates health insurance costs via an indirect approach that’s based on the retained earnings of health insurers.

The BLS calculates this number ONCE per year, with the overall change being reflected across the rest of the year in fairly evenly spread MoM changes.

In October 2021, this adjustment saw a MoM increase of 2.0%. Over the year to September 2022, individual MoM changes averaged 2.1%, with the YoY growth rate peaking at 28.2% in September 2022.

In October 2022, the BLS re-adjusted the figure DOWNWARDS by 4%! From October 2022 to January 2023, the average MoM change has been -3.8%. Should this average hold until the next annual revision in October 2023, the CPI health insurance component will have DECLINED by 37.2%.

While this will have a significant impact on lowering core CPI services prices until September 2023, there is an argument to be made that this technical measurement approach distorts the underlying core services inflation picture.

In order to avoid this lumpy, technical, indirect adjustment from clouding the picture, we can add health insurance to the list of items of which to exclude.

Once this is done, we can see that core services prices continue to see MoM growth that remains well above average historical monthly levels — albeit less significant than the levels seen from March to June 2022.

A key driver of this divergence is motor vehicle maintenance & insurance prices. Recreation services and other personal services continue to also record higher than average price growth. The other components of medical care services (which continue to be included in the above chart) are not a major driver of the larger than usual price growth being seen in adjusted core services.

The bigger picture: understanding price drivers & lags, shows that the disinflation picture remains firmly intact

While many see the continued elevated nature of some core services prices as a reason for concern, they can’t be looked at in isolation. They need to be observed as part of the bigger picture.

As many people point out, services prices are more “sticky”, they are also the most lagging. Unlike commodities such as oil, that are traded on a daily basis, or durable goods, where new shipments are often made relatively frequently, with production costs finely calculated, the prices of many services tends to remain more static. One reason for this, is that services are often more difficult to cost and price, with there often being a less clear indication of how input costs change at a unit level, on a day-to-day basis.

For instance, your local hairdresser isn’t going to know the minute detail of how changes in their electricity rates and hairdressing supplies are impacting the cost of a single haircut on a day-to-day basis — though they will gain an idea of patterns emerging over several months. It can thus take time for price changes to occur, and once they do, they will stay there for longer, given this very dynamic.

Looking squarely at services prices thus provides a misleading picture, for they aren’t indicative of where broader prices are heading, but of where broader prices have ALREADY headed.

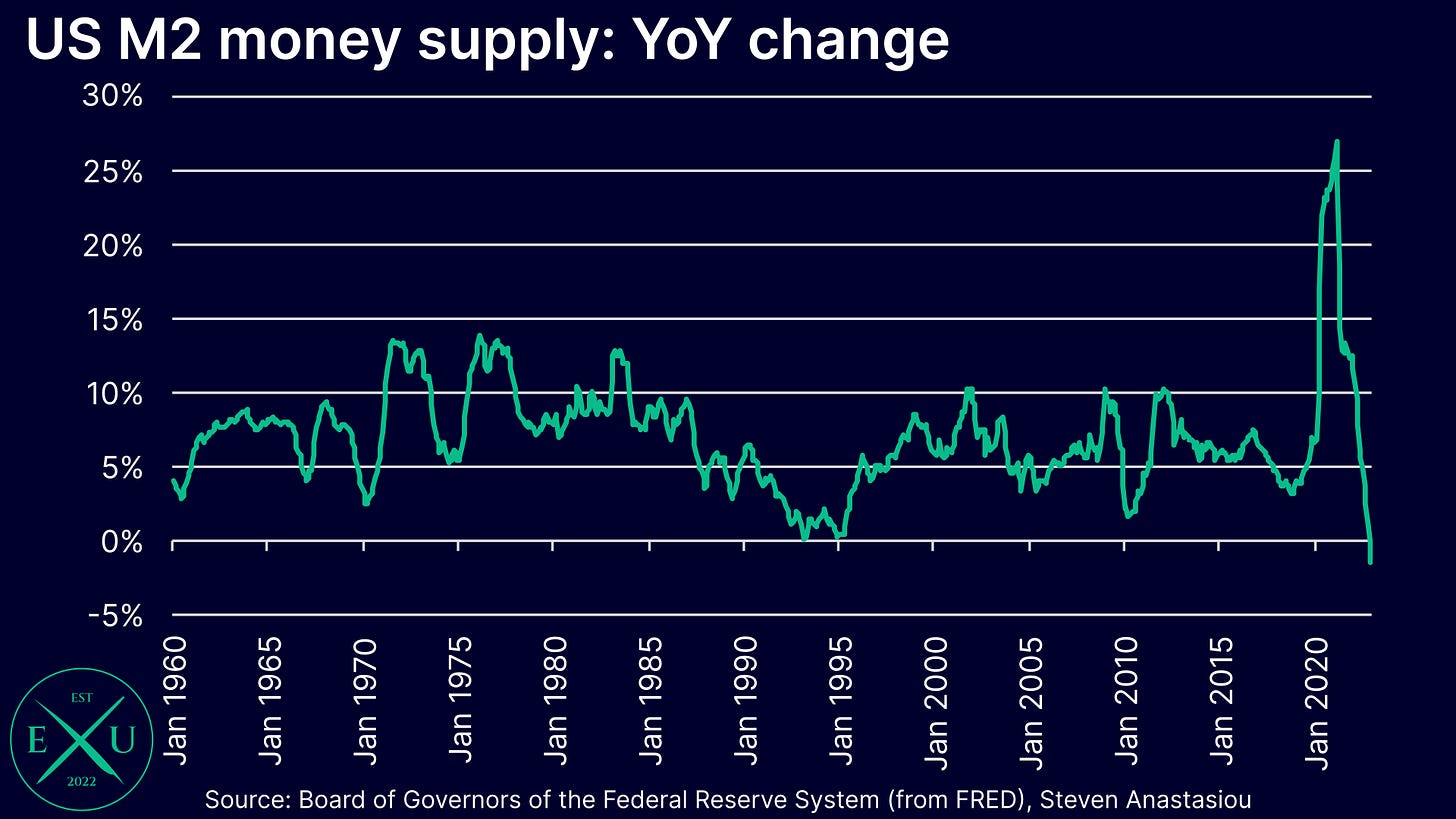

Let me explain how this has actually played out in practice, by detailing how the current inflation cycle evolved. It begun with the federal government’s HUGE budget deficits, with the dishing out of stimulus checks and other pandemic related measures, resulting in an ENORMOUS increase in the money supply.

With individuals locked up at home, it resulted in an enormous surge in demand for durable goods. As a result, prices rose here first. As inventories were cleared and suppliers needed to respond to new orders, as well as broader movements picking up post the lifting of lockdowns, commodity prices then rose (nondurables).

Services prices, already the most lagging in terms of price changes, were even more lagging during this inflation cycle, given the impact of lingering movement & social restrictions.

The manner in which the COVID environment impacted the distribution of the newly printed money, and thus prices, can be seen in the below overview of YoY CPI price growth, broken down by the three key categories. Durables rose first, follow by nondurables, followed by services (in a much more smoothed manner).

Fed Chair Jerome Powell stated at the last FOMC press conference that he can now say that the disinflationary process has begun, yet in actual fact, one could argue that the disinflationary process began after durables prices began disinflating in March 2022 — this marked the initial turning point for the current high inflation cycle, with durables being the most leading indicator.

In due course, nondurables prices followed, with oil and gasoline prices continuing to remain in a downtrend despite enormous supply disruptions — why? A key reason is the impact to demand from outright declines in the M2 money supply.

Instead of recognising this inflationary process, people simply look at “sticky” services prices and say “the Fed needs to do more!” — not so.

The disinflationary process is underway, and as long as M2 continues to fall, or grow at only a modest rate, and barring a major oil supply shock, it will continue. Services prices are simply the most lagging component of the inflation/disinflation cycle, and are playing catch up to durables and nondurables price movements. Though in time, they too, will roll-over, and reflect the underlying reality of a declining money supply. All the Fed needs to do, is wait.

While I expect the Fed to instead continue tightening, all it will achieve, is a bigger recession down the road — it won’t materially help the inflation picture. For the underlying inflation dynamic has already shifted. Services prices simply need more time to reflect it.

Don’t get lost in the noise of a month or two of higher MoM CPI growth, which will remain volatile due to energy prices, and will be impacted by the seasonal trend for greater price pressure during January — May.

The disinflationary thesis remains firmly intact.

Thank you for continuing to read and support my work — I hope you enjoyed this latest piece.

In order to help support my independent economics research, which aims to provide not just hedge funds & asset managers with access to institutional grade research & insights, but ordinary people, please like and share this article.

If you haven’t already, make sure to subscribe so that you don’t miss an update — it’s free!

Perfect!