What the latest US Treasury QRA means for the economy & markets

A decline in outstanding T-bills is set to exacerbate Fed tightening, but the market impact of increased net coupon supply is nuanced, with gross issuance likely below market expectations.

Executive summary

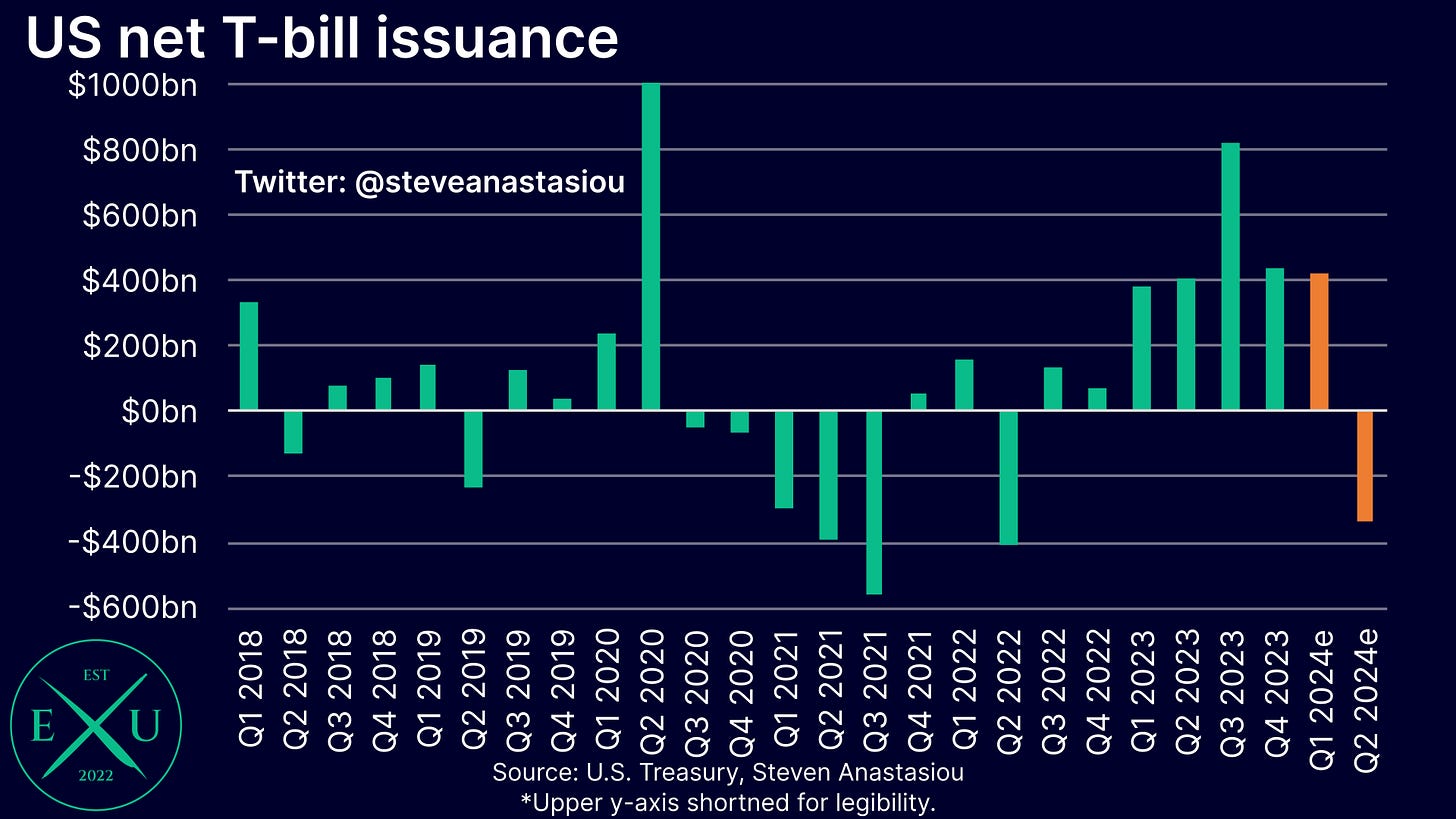

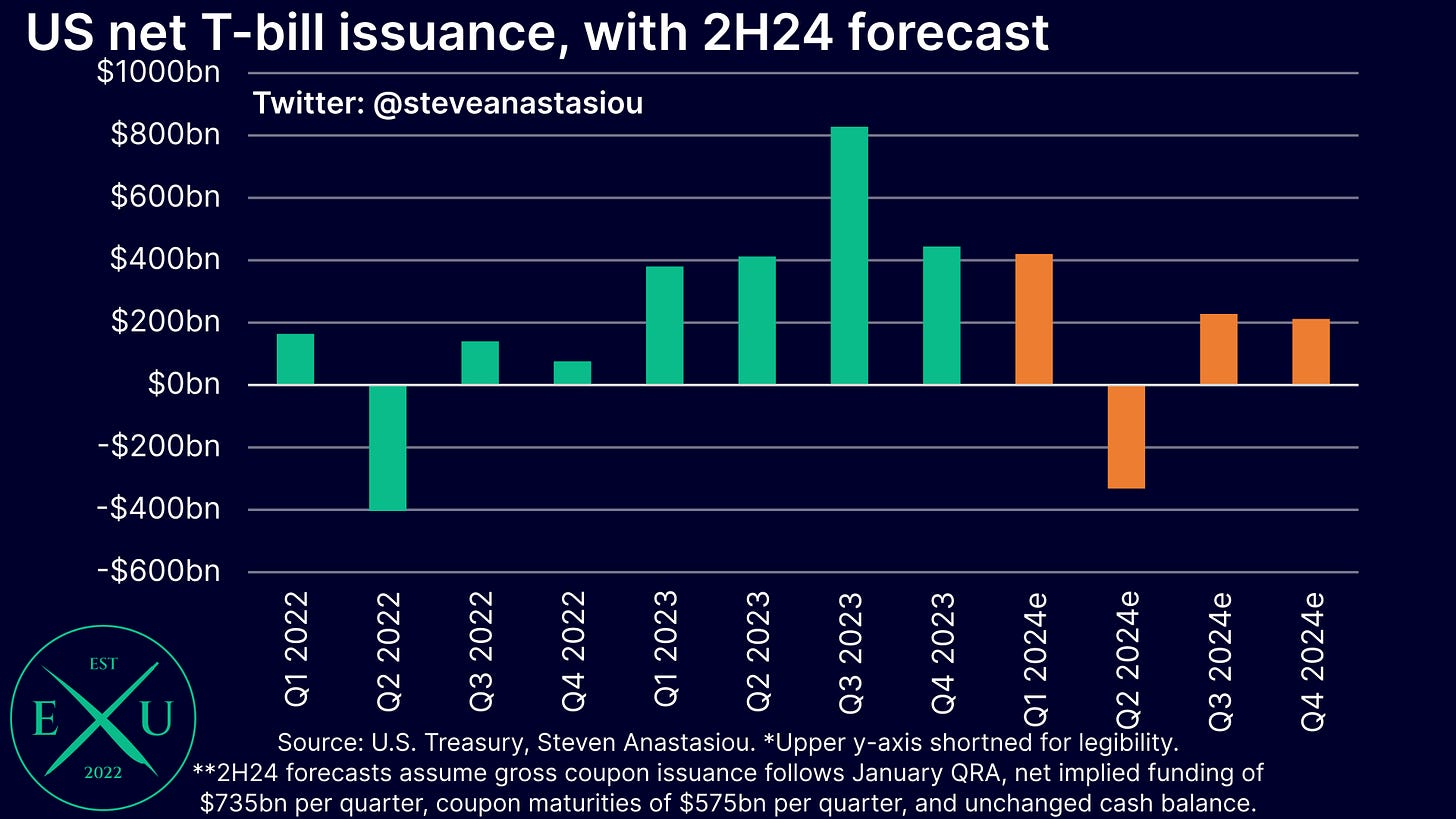

After seven consecutive quarters of material net T-bill issuance, the level of outstanding T-bills is expected to fall by over $300bn in 2Q24. Meanwhile, net coupon issuance is expected to rise above $500bn in 2Q24.

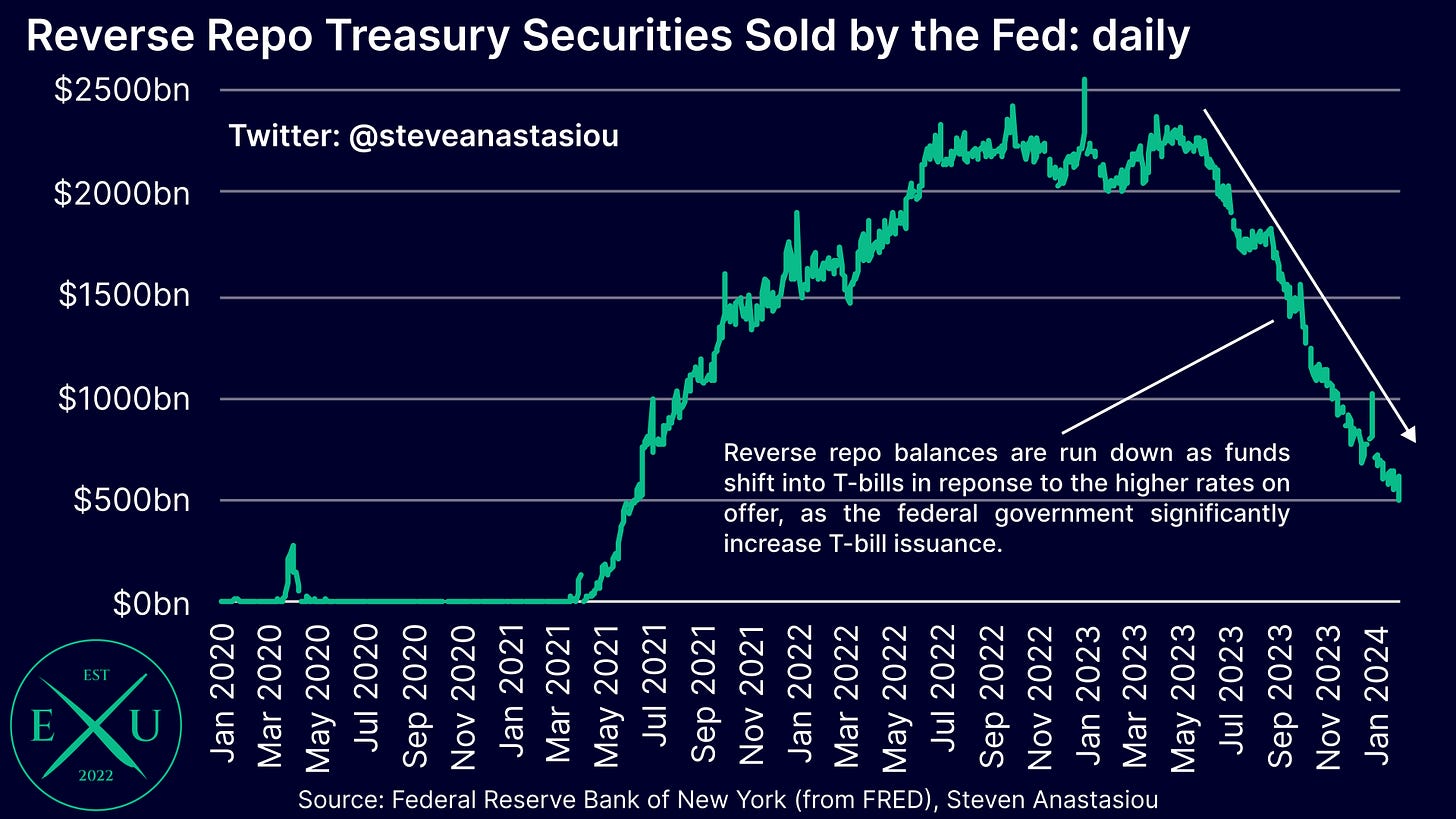

When net T-bill issuance is funded by withdrawals from the Fed’s RRP facility, and this is used to fund the government deficit (as opposed to building the federal government’s cash balance), this acts to shift “idle” funds into the “real” economy, providing an economic stimulus. With the RRP facility recording a huge decline as quarterly net T-bill issuance has averaged >$500bn across 2Q23-1Q24e, this is likely a material reason behind the acceleration in real US GDP growth in 2H23.

The absence of this stimulatory offset to the Fed’s tightening in 2Q24 is likely to significantly increase downward pressure on commercial bank deposits and the M2 money supply. In-turn, this is likely to place further downward pressure on inflation and economic growth, while adding to pressures in the banking system.

Though it’s important to note that given a continued large federal government deficit, the decline in outstanding T-bills is expected to be temporary — I currently expect large net T-bill issuance to return in 2H24. This is likely to once again result in large declines in the Fed’s RRP facility, providing a stimulatory offset to the Fed’s tightening.

With T-bill supply currently expected to decline for only one quarter, and a further material batch of net T-bill issuance yet to come in 1Q24 (expected to be broadly equivalent to the estimated decline in T-bills during 2Q24), this suggests that the US economy (which has so far remained relatively resilient) will be able to weather the temporary reversal of this stimulatory impulse in 2Q24. Though with US banking sector concerns resurfacing in recent days and several signs of a material weakening in the jobs market being seen in December’s employment data, the temporary removal of the stimulative offset to the Fed’s tightening, does raise the risk of a material shock occurring in 2Q24, versus the conditions that have prevailed in recent quarters.

While many may have expected the significant increase in net coupon issuance to cause a renewed rise in bond yields (as was seen post the August refunding announcement), the increase in gross issuance was already telegraphed in the November refunding announcement. Indeed, the actual amount of gross issuance delivered in 1Q24 and recommended for 2Q24, was slightly below what was telegraphed in November, with cuts made to 10- and 30-year issuance recommendations. This likely explains much of the decline seen in 10-year bond yields post the latest refunding announcement.

The latest quarterly refinancing announcement (QRA) from the US Treasury has revealed that net T-bill supply is expected to drop by over $300bn in 2Q24.

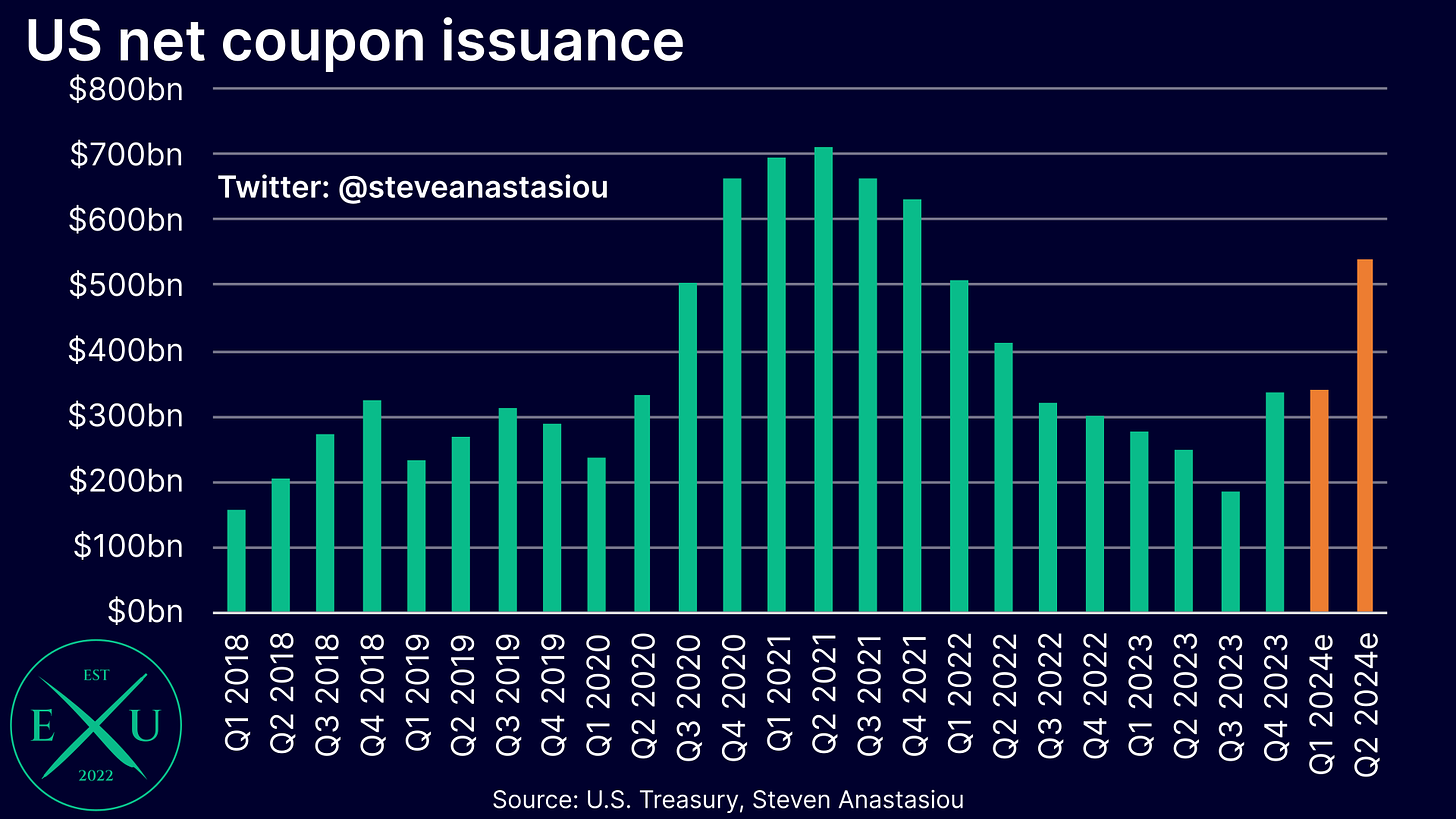

At the same time, net coupon issuance is expected to rise above $500bn for the first time since 1Q22.

What does this mean for the economy and markets? To answer this question, allow me to first explain what has been happening with Treasury refunding, and the interaction with the Fed’s RRP facility, over recent quarters.

High RRP balance allows the Fed to vastly increase net T-bill issuance, while keeping duration issuance muted

Despite a major federal government deficit that has continued to grow, for nine consecutive quarters, from 3Q21 to 3Q23, the US Treasury reduced its net coupon issuance.

While much of the decline in net coupon issuance can be explained by the federal government drawing down its cash balance from $945bn in May 2022, to a low of $45bn in June 2023, as debate over the US debt ceiling played out, lower net coupon issuance has also been supported by the major increase in net T-bill issuance in 2023.

On account of the enormous sums sitting in the Fed’s reverse repo (RRP) facility, the shift towards a large increase in net T-bill issuance, has been made easy.

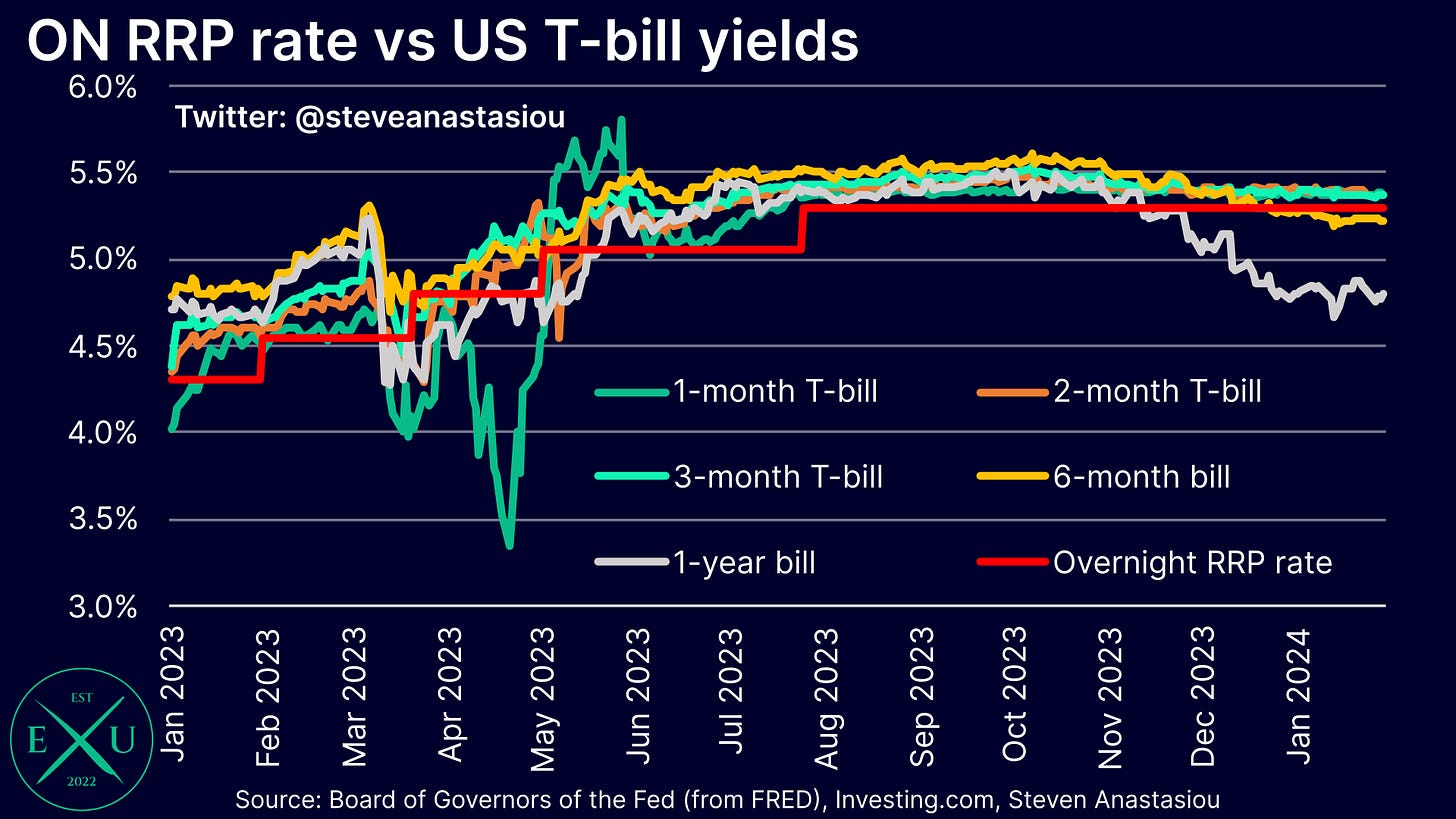

The Fed’s RRP facility can be thought of as consisting of “idle/inert” funds, and is used by the Fed to “mop up” excess liquidity, in order to put a floor on interest rates — in order to achieve this goal, the Fed pays interest on RRP agreements (the rate currently paid, is 5.3%).

In light of the enormous QE and federal government debt monetisation that occurred post-COVID, an enormous amount of funds ended up in the Fed’s RRP facility, which peaked at ~$2.5tn.

Though as a result of the very large net T-bill issuance that has been seen since 1Q23, short-term interest rates have consistently been above the rate paid by the Fed on its RRP facility.

This encouraged money market funds (MMFs) to reallocate funds from the Fed’s RRP facility, into T-bills. As a result, the RRP facility has fallen to ~$504bn, as of 1 February.

Given that balances held in the RRP facility are effectively inert/idle funds, to the extent that this shift into T-bills has funded the federal government deficit, this acts to unleash idle funds into the “real” economy.

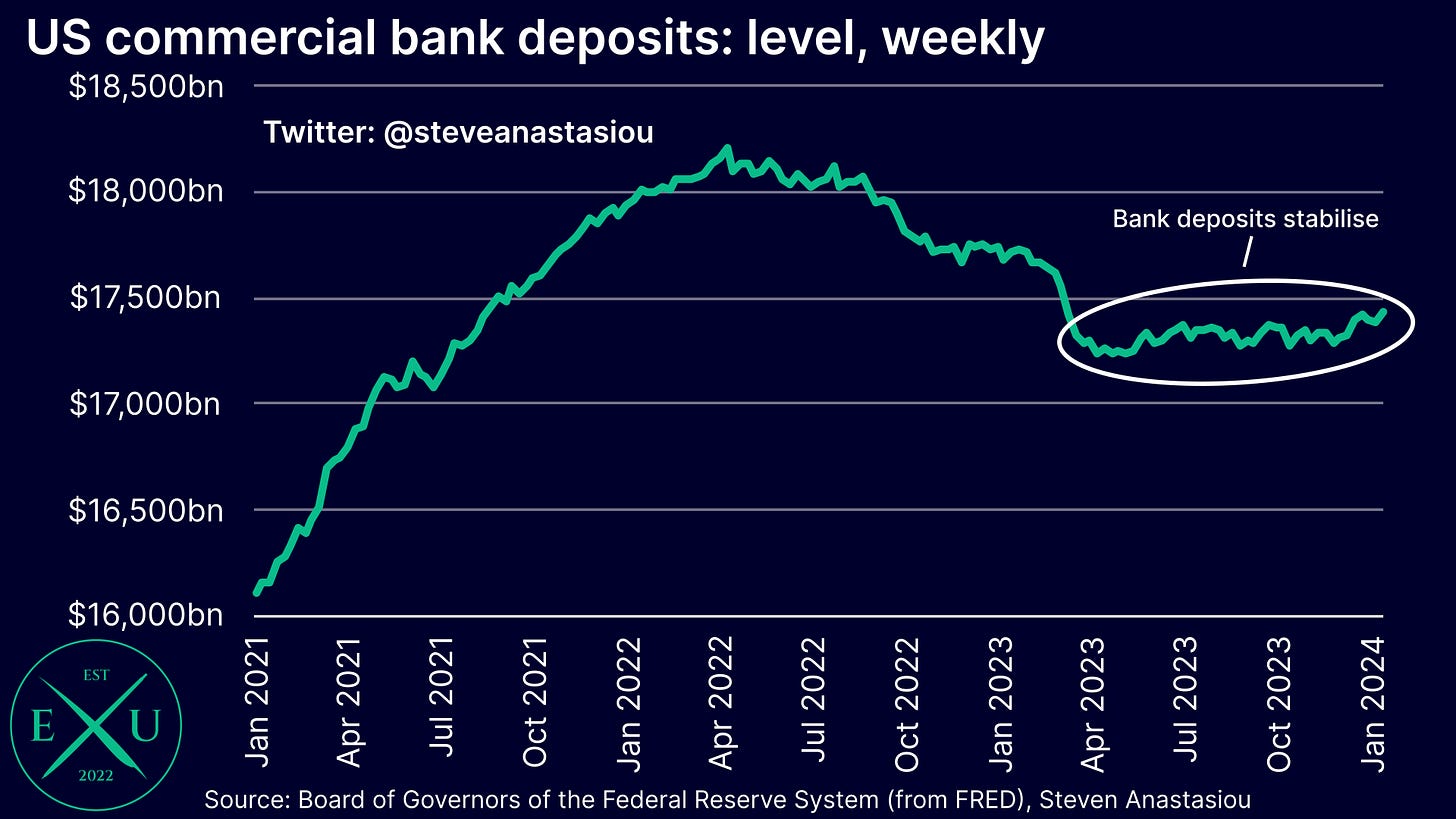

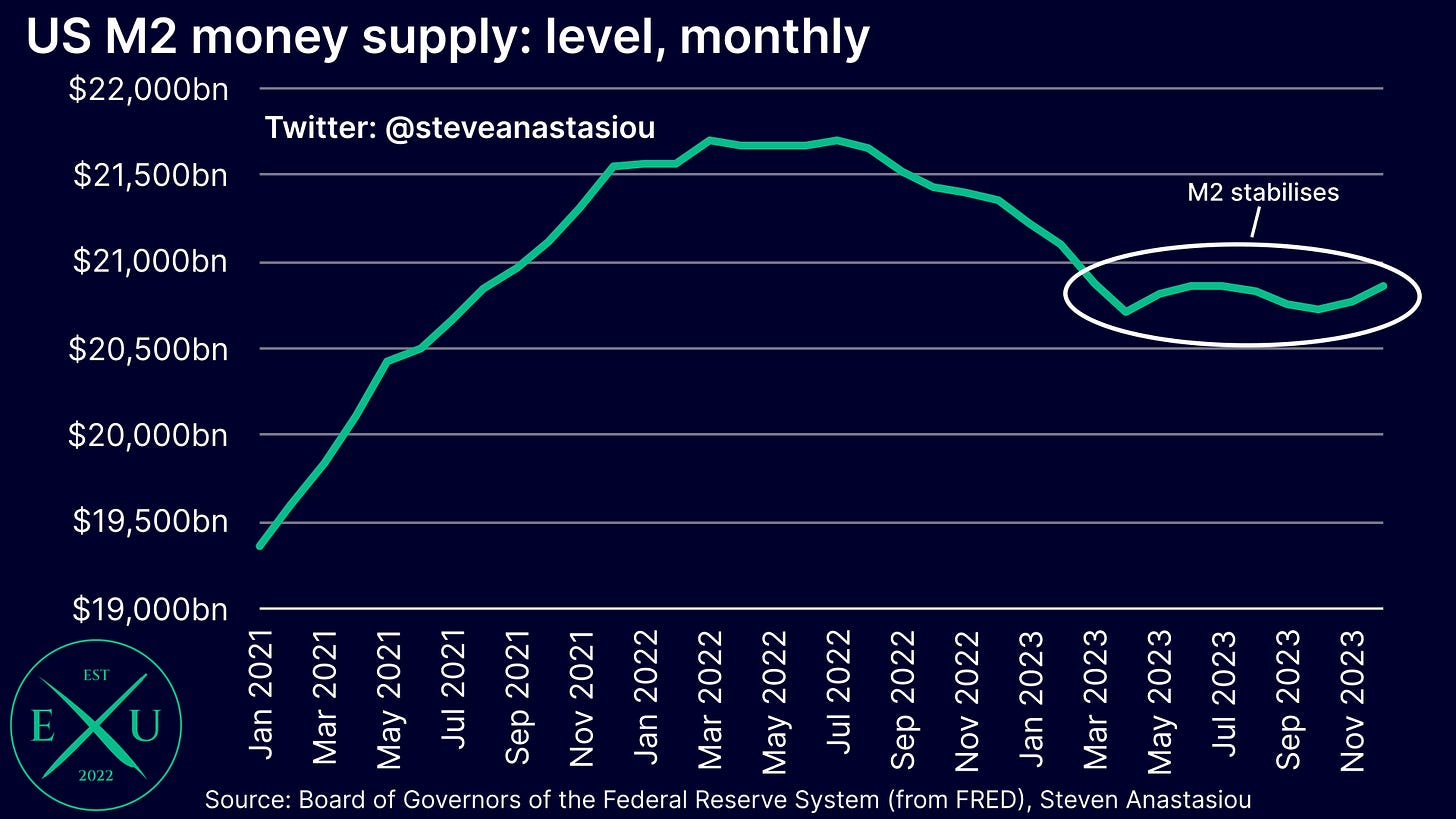

The stimulatory impulse of this shift, which has acted to offset the Fed’s significant tightening, can be seen in the stabilisation of commercial bank deposits and the broader M2 money supply, since the Fed’s RRP facility began to decline in May 2023. Alongside this significant stimulatory impulse, real US GDP growth accelerated in 2H23.

Reversal of outstanding T-bill issuance to put further downward pressure on bank deposits and M2

Now that the underlying backdrop of the past several quarters has been explained, we can turn our attention to the latest QRA, which is set to see the script flipped in 2Q24.

Given that the second quarter of the calendar year encompasses the most significant period of tax receipts for the US government, it’s important to realise that federal government borrowing needs are generally at their seasonal low during this period.

With funding requirements at their seasonal trough, and net coupon issuance rising materially (as discussed later), the Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee (TBAC) has recommended that a material amount of maturing T-bill issuance is not replaced with new T-bill issuance in 2Q24. The quantum of the expected decline in outstanding T-bills for 2Q24 is over $300bn.

Given not only the significant size of this runoff, but the enormous relative shift from average quarterly estimated net T-bill issuance of over $500bn from 2Q23-1Q24e, the impact on the economy is likely to be material — i.e. not only is the US economy not going to receive a major stimulatory impulse from “idle” RRP funds moving into the real economy in 2Q23, but some of the stimulatory impulse is likely to reverse, as MMFs are forced to reallocate some of their maturing T-bill funds, of which a significant portion may end up back at the Fed’s RRP facility.

This is likely to result in renewed downward pressure on bank deposits and the M2 money supply in 2Q24.

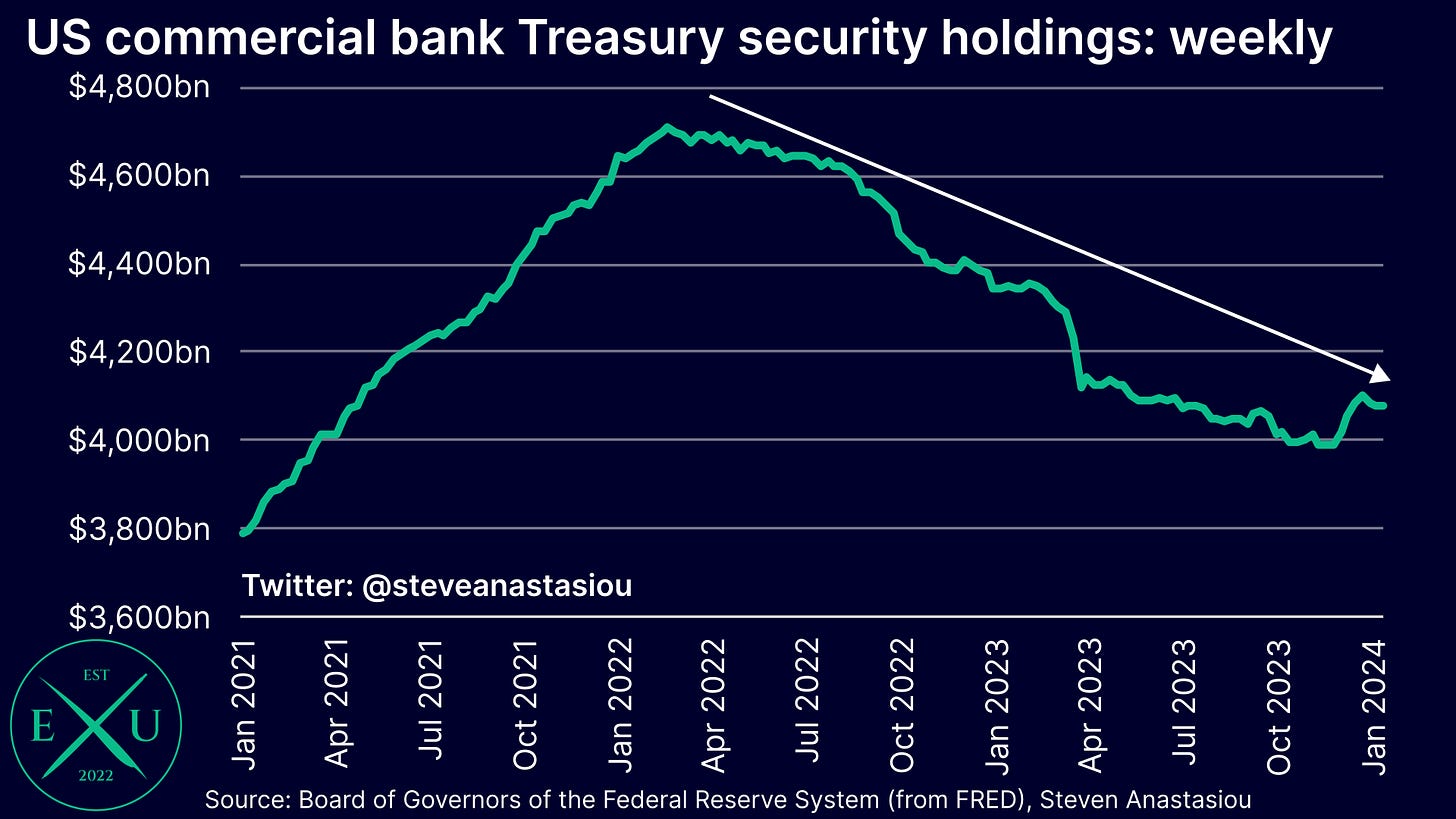

In-turn, this could encourage a renewed decline in commercial bank security holdings (in order to help fund deposit outflows), at a time when the Fed’s BTFP program is scheduled to have already expired. Such an outcome would have the potential to cause significant realised losses for some banks, which could create further instability in the banking sector.

This contractionary economic impulse comes as a wave of renewed concerns has recently arisen over the outlook for US regional banks, with the SPDR S&P Regional Banking ETF falling 8.8% over the past two days.

Looking at the economy more broadly, renewed declines in the M2 money supply are likely to put further downward pressure on inflation and economic growth.

Large federal government deficit likely to see a shift back to large net T-bill issuance in 2H24

While net T-bill issuance is expected to contract significantly in 2Q24, with the federal government continuing to run a very large deficit, the decline in net T-bill issuance is expected to only be temporary.

Assuming increases in privately-held net marketable borrowing of $735bn in 3Q24 and 4Q24 (which results in an estimated $2.5tn of net implied funding for CY24 versus a current primary dealer median estimate of $2.5tn for FY24), gross coupon issuance in-line with the January QRA, average quarterly coupon maturities of $575bn in 2H24 (versus an estimated average of $573bn across 3Q23-2Q24e) and an unchanged cash balance, suggests that quarterly net T-bill issuance is likely to average more than $200bn in 2H24.

This is likely to prompt a renewed drain of the Fed’s RRP facility, with the potential for it to be virtually fully extinguished in 2H24. While this would provide a further stimulatory offset to the Fed’s tightening in 2H24, it sets up the economy to enter 2025 without a stimulatory offset, and without an abundance of liquidity.

Will the economy hold out until large T-bill issuance returns?

Given that a decline in bills issuance is likely to only be temporary, the key question is whether the reversal of the stimulative offset to the Fed’s tightening for a single quarter, can be enough to put the US economy significantly off course.

While the major moderation that has been seen in the hiring rate, and private payroll growth, suggests that the labour market remains vulnerable to further downward pressure in the M2 money supply, an acceleration of real GDP growth in 2H24 (albeit caveated by GDI, which recorded much more modest growth in 2Q23/3Q23), suggests that the US economy should be able to weather one quarter of a reduction in net T-bill issuance.

Further suggesting that the US economy can weather the expected decline in outstanding T-bills in 2Q24 relatively well, is that the US Treasury estimates that another $300-$350bn of additional net privately-held T-bill supply is slated to be issued in February and March. As a result, the 2Q24 drain in net T-bill issuance, is likely to be offset by the additional net T-bill issuance that is due to occur during the next two months.

While this suggests no net stimulatory/contractionary impact from net T-bill issuance over the next five months in aggregate, the net impact on the economy is not equally netted out, as QT and significantly positive real rates will continue to have a contractionary influence.

While consensus would ultimately view that the US economy remains on track to record robust growth throughout 1H24, given the latest bout of renewed concerns over the banking sector, and the signs of a significant weakening seen in the US jobs market in December, the temporary removal of the stimulative offset to the Fed’s tightening, does raise the risk of a material shock occurring in 2Q24, versus the conditions that have prevailed in recent quarters.

Higher coupon issuance would ordinarily pressure yields and put downward pressure on equities — but has the increase already been priced in?

Focusing now on coupons, the TBAC recommended another increase in gross coupon issuance for 2Q24. This is currently expected to result in net coupon issuance rising above $500bn in 2Q24, marking the highest rate of net coupon issuance that has been seen since 4Q21.

Note that given maturity restrictions, MMFs cannot absorb coupon supply, meaning that the stimulatory shift from MMFs reallocating cash from the Fed’s RRP facility to T-bills, does not apply to net coupon supply.

Furthermore, given that commercial bank Treasury holdings have declined significantly over the past two years, and that commercial bank security holdings may come under further pressure in 2Q24, this duration issuance will likely need to be largely absorbed by the non-bank private sector.

In isolation, increased net coupon issuance would be expected to put upward pressure on bond yields. Furthermore, given that this coupon issuance will likely need to be absorbed by the non-bank private sector, and that coupon issuance carries greater duration risk, it would ordinarily be expected to put downward pressure on other risk asset prices (such as equities), as in order to absorb increased duration (which carries increased risk), there would likely be some reallocation out of other risk asset classes (as opposed to just using cash balances or borrowing the difference).

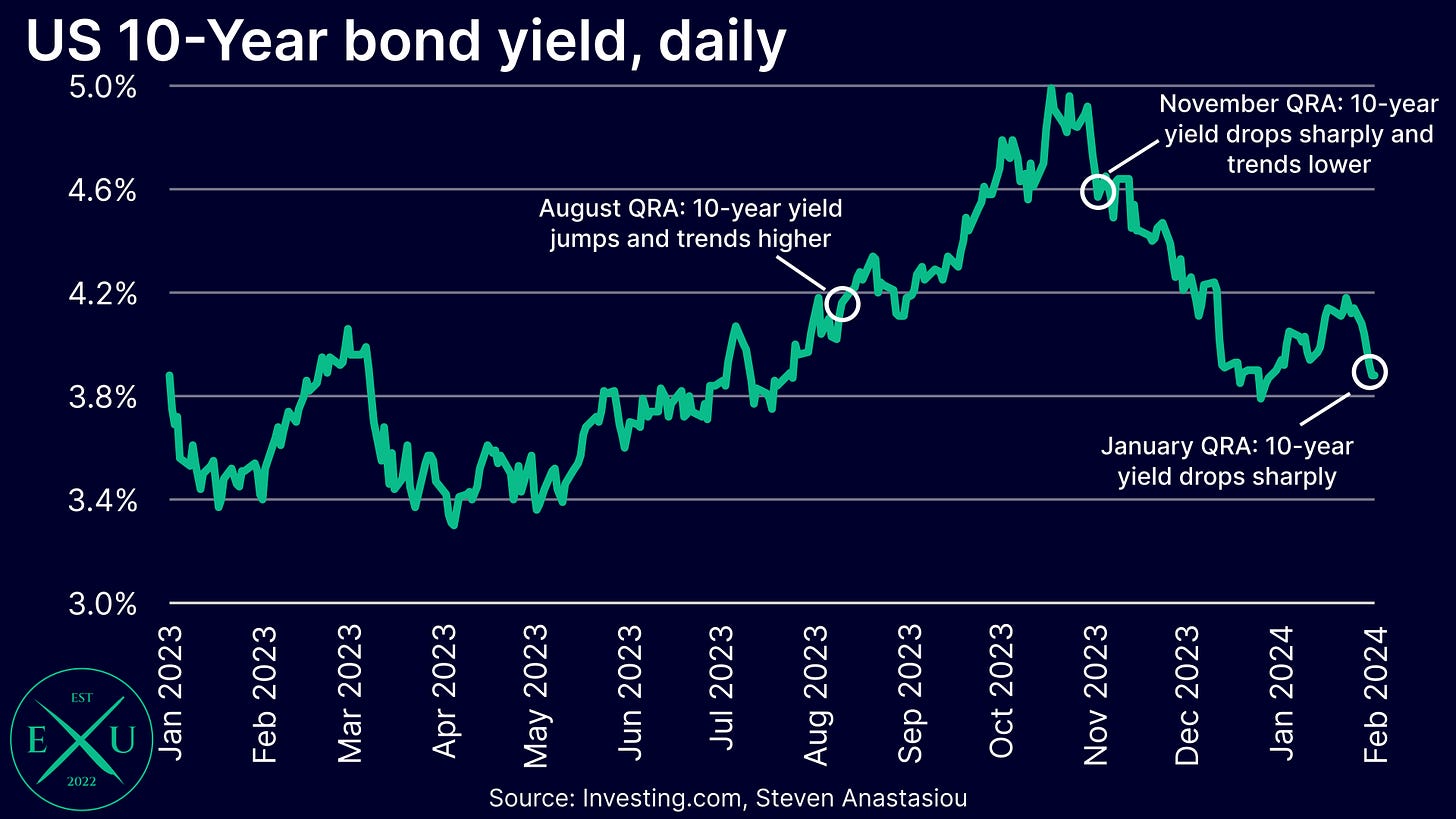

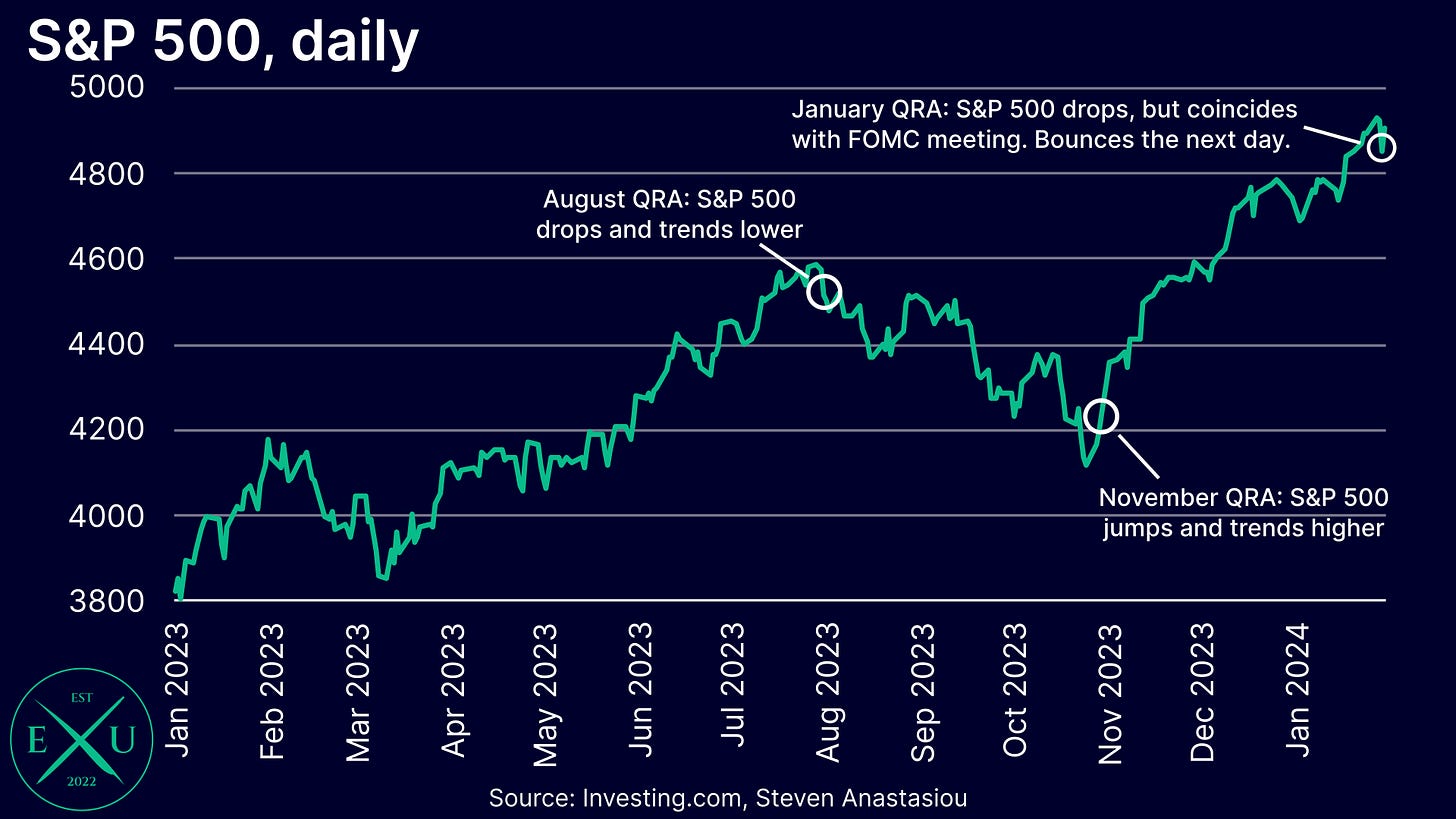

In order to understand the impact that Treasury refunding announcements can have on markets, and why the current market impact may be more muted this time around, we need to look back at the market shifts that occurred in response to the August and November QRAs, and what they recommended for future gross coupon issuance.

The August QRA significantly unnerved markets, with the TBAC recommending a significant increase in net coupon issuance, so as to ensure that the outstanding level of bills does not rise too far above the TBAC recommended range of 15-20% and returns to the recommended range over time.

As a result, net coupon issuance rose dramatically in 4Q23, to $338bn, from $185bn in 3Q23. Furthermore, the TBAC issued a scenario analysis that argued for very significant additional increases in gross coupon issuance over the following quarters.

The market reaction over the ensuring months was severe, with treasury yields surging, and equities tumbling.

In response to this aggressive market reaction, the November refinancing update significantly wound back the August recommendations. Now, the TBAC recommended “meaningful deviation in the medium-term” to its guidance that T-bills make up 15-20% of outstanding debt (i.e. that net T-bill issuance remain elevated) and that Treasury “consider tilting issuance toward tenors less impacted by the rise in term premium and those that benefit from greater liquidity premium”.

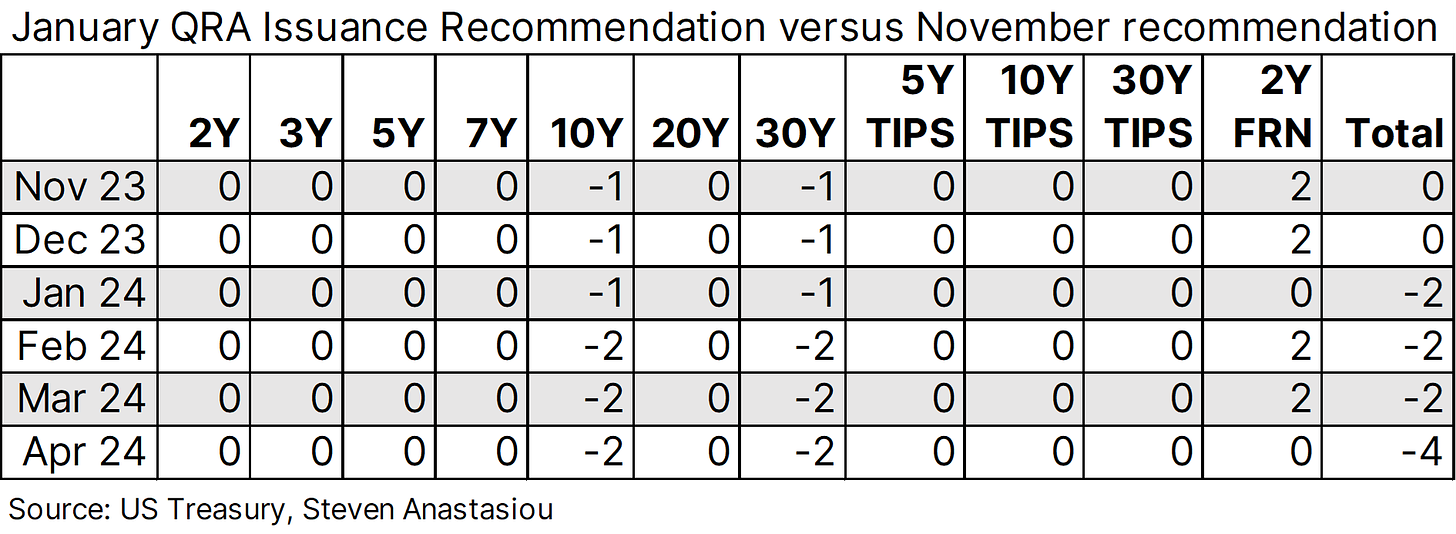

As a result, gross coupon issuance for 4Q23 ended up being $921bn, versus the implied August neutral issuance scenario of $951bn.

Furthermore, the recommended issuance announced for 1Q24 was below that outlined under the August neutral issuance scenario, whilst the outlook for coupon issuance beyond that date was also revised materially lower, with the November update noting that one similar increase to that announced in November was likely in the next QRA (as opposed to the more significant increases proposed under the prior August neutral issuance scenario), and that “increases beyond Q2 FY2024 may not be required.”

As a result of this shift, 10-year bond yields tumbled, and equity markets rallied.

This brings us to the latest update, where despite a major increase in net coupon issuance, bond yields have fallen materially. While the reaction to the major increase in net coupon issuance following the August QRA may have left some surprised by this move, there’s one very important factor to consider: market expectations.

The huge jump in net coupon issuance in the August QRA, combined with the updated neutral issuance scenario, caught markets significantly by surprise.

This time around, the increase in gross coupon issuance was already telegraphed at the November QRA — “at this point, the Committee expects that the need for similar further increases at the Q2 FY2024 meeting is likely” (note that the Q2 FY2024 meeting equates to the January QRA).

While a similar increase was delivered, the total quantum of gross issuance was below the rate recommended during the November QRA.

At the November QRA, gross issuance was slated to rise to $372bn in April, but this was revised to $368bn in the latest QRA, with reductions made to the 10- and 30-year issuance recommendations.

With this slight reduction in issuance recommendations carrying forward to current estimates that extend until July, the net impact of this latest increase in gross issuance, is likely to have been below market expectations, helping to explain why bond yields have rallied since the latest QRA was announced — though the aforementioned renewed concerns surrounding the US banking sector, may have also had a material influence.

Thank you for reading my latest research piece — I hope that it provided you with significant value.

Should you have any questions, please feel free to leave them in the comments below.

In order to help support my independent economics research, please consider liking and sharing this post and spreading the word about Economics Uncovered — your support is greatly appreciated!

If you haven’t already subscribed to Economics Uncovered, subscribe below so that you don’t miss an update.

This is terrific. I like to think that I understand this stuff, but you put me to shame. I've been puzzled by the 4Q financial markets and now I understand them much better. A couple of questions:

To your knowledge, do bank reserves play any role at the Fed whatsoever? If so, do you know what "excess" reserves might be?

I think we must keep an eagle eye on bank liquidity and capital regs especially with the possible passage of "Basel End-game." If banks start losing deposits again through Fed operations, they will try to hang on to shorter term treasuries. The only lever they will have will be to reduce lending. We could easily have a nasty credit crunch. I'm not convinced that monetary authorities are fully aware of this danger.

Every American has a conspiracy theory these days, and this is mine: I think Chair Powell HATES Donald Trump and he is setting things up to ease sharply around midyear to get Biden elected. Which is pretty much what Arthur Burns did. Whew. Biden or Trump. Talk about a Hobson's choice.

always insightful!!