As long as the Fed keeps tightening, the banking crisis will grow

Aggressive rate hikes and QT are reducing bank deposits and the value of bank assets - a combination that will see banking sector stress continue to grow.

Many believed that after First Republic Bank was dealt with, that the US banking crisis would fade away, with the “weak” links having now been dealt with.

Though on the contrary, as long as the Fed continues its aggressive tightening — which includes not just its aggressive interest rate rises, but also its quantitative tightening (QT) — banking sector stress will only continue to grow, leading to additional bank failures.

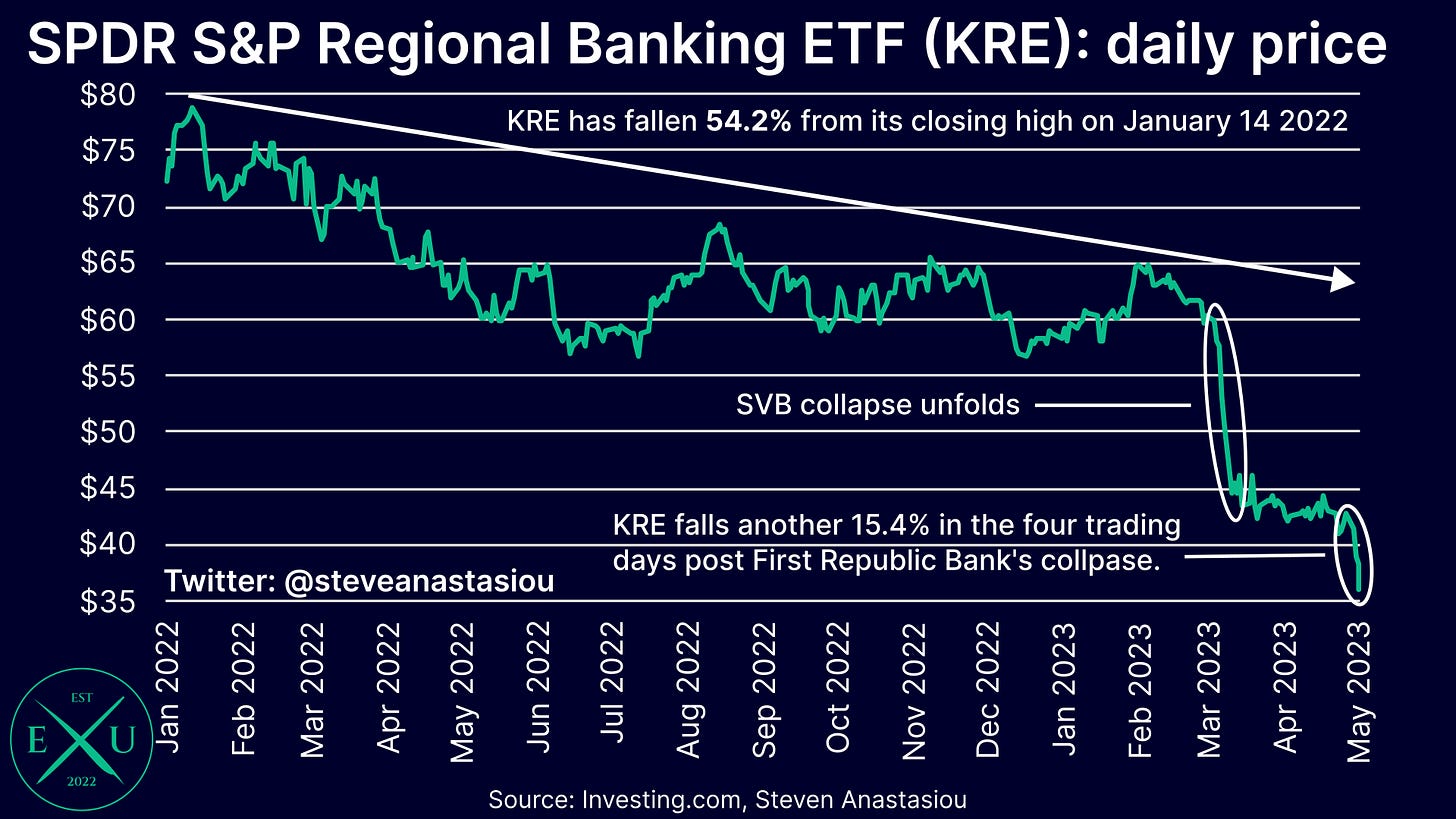

The market reaction in the four trading days since First Republic’s collapse, which has seen the SPDR S&P Regional Banking ETF (KRE), plunge 15.4%, has awakened many to this reality.

Fractional reserves make banks vulnerable to falling deposits

When an individual or business deposits money into a bank, the bank does not keep all of the cash locked away in a vault. In proportion to their customer deposit liabilities, banks instead only hold a fraction as cash assets, with the rest of their assets generally comprising of loans, or investments into securities such as Treasuries.

Given that banks only hold a fraction of customer deposits as cash on their balance sheet, net declines in deposits (i.e. net customer withdrawals), impact a bank’s liquidity, as in order to meet these withdrawals, they must dispose of their own cash assets. In the event that banks suffer a severe deposit outflow, it can thus result in a bank failing.

Bank cash assets have fallen significantly since Q4 2021

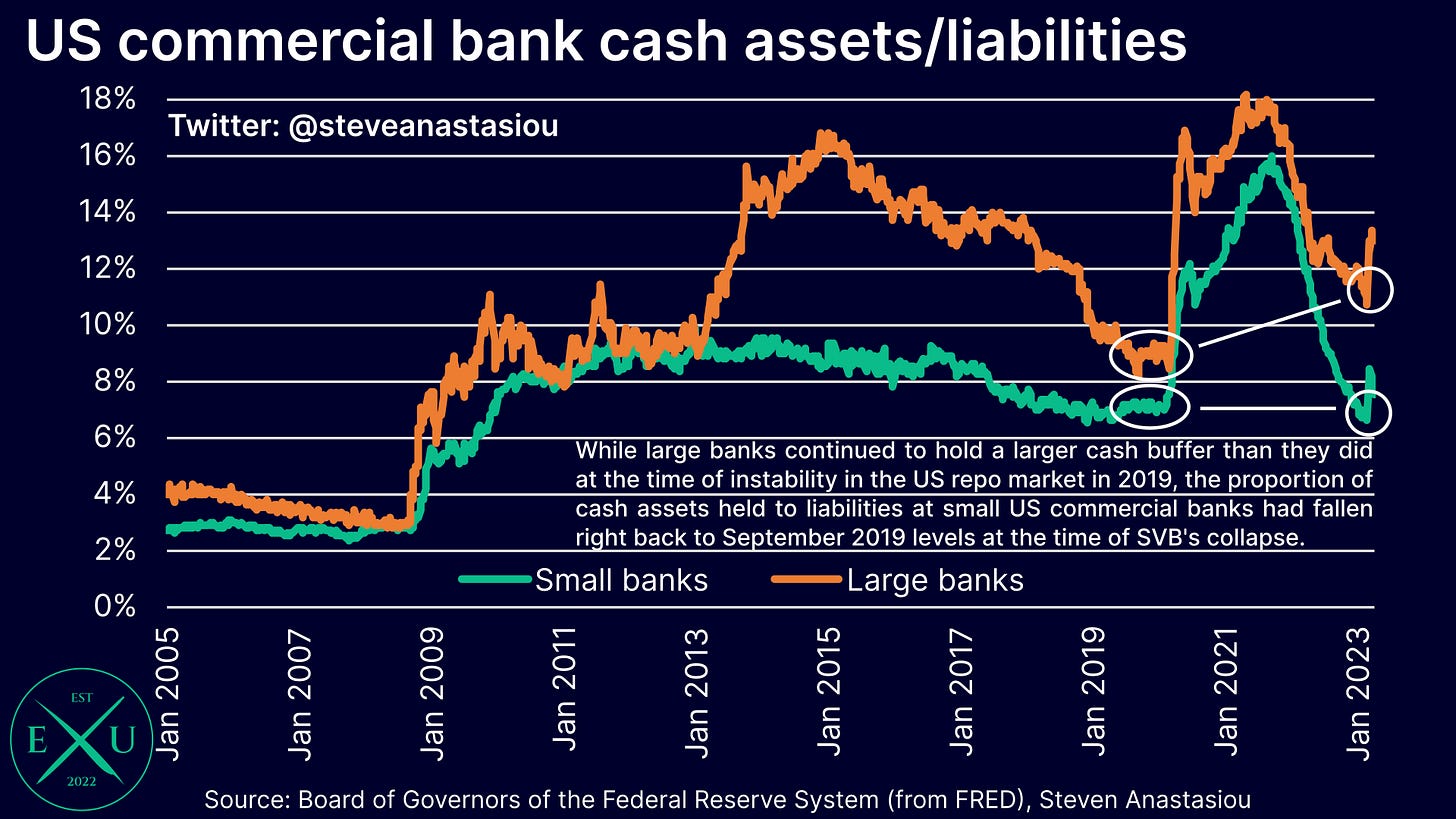

In proportion to their liabilities (most of which are deposits), cash assets of US commercial banks have been falling since Q4 2021.

While large US banks continue to hold a larger share of cash in relation to their liabilities than they did pre-COVID, the ratio of cash assets to liabilities at small US banks recently reached levels that were seen in September 2019. This is an important time period, as this was when the US repo market experienced a period of turmoil, prompting the Fed to inject additional liquidity.

Rising interest rates have made it more difficult for banks to bolster their liquidity by selling assets

In order to bolster their cash levels, banks can sell some of the other assets they hold, such as their fixed income securities.

Though given that interest rates have risen so significantly, the value of fixed income securities have fallen significantly.

Therefore while the sale of fixed income securities helped Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) to bolster its liquidity in the face of falling deposits, it also resulted in it incurring ~$1.8bn in after-tax losses. In response to these losses, SVB then sought to raise additional capital. Once investors heard the news, SVB’s stock price plunged. A bank run ensued, and SVB failed.

In response to SVB’s collapse, the Fed implemented the Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP). The BTFP provides loans to banks based on the par value of eligible collateral that they provide. By lending at par value, the BTFP allows banks to improve their liquidity without having to sell securities at a loss.

So, problem solved? Not so fast.

The BTFP treats the symptom, not the disease. As such, despite receiving $13.8bn from the BTFP, First Republic Bank failed anyway.

As First Republic showed, if deposits keep falling, even the liquidity that the BTFP can provide, won’t be enough.

How about selling loans to help improve liquidity? Again, just as is the case with fixed income securities, fixed rate loan values have fallen as interest rates have risen. Selling loans that have fallen in value would thus incur losses.

As banks are heavily leveraged, incurring losses can significantly impact their capital position. With capital raisings having a dilutive impact on existing shareholders, this will put downward pressure on a bank’s share price. It can also significantly hamper investor confidence, leading to an even larger share price decline.

This creates further problems, as a lower market cap increases the equity dilution that would take place in the event that a bank needs to raise additional capital. This can further rock investor confidence, increasing solvency concerns and encouraging further share price declines, in what can form a vicious cycle.

Why not just pay more for deposits? Again, it’s about profitability — meanwhile, the Fed’s QT is also contracting deposits irrespectively

Many suggest that in order to stop the deposit bleed, banks should simply increase the interest rate they pay on deposits. While some banks have done just that, given that bank assets are locked in at fixed rates, increasing their deposit rates can significantly erode their profitability.

Importantly, so too does the use of facilities like the BTFP, which charges interest at the one-year overnight index swap rate, plus 10bps.

Again, an erosion of bank profitability risks material share price declines, while the potential for outright losses may necessitate capital injections, thus causing further share price declines and increased concerns around a bank’s solvency.

Such an outcome also risks hampering depositor confidence and causing a further deposit run, negating the benefit to deposit levels that can be achieved from banks paying higher interest rates.

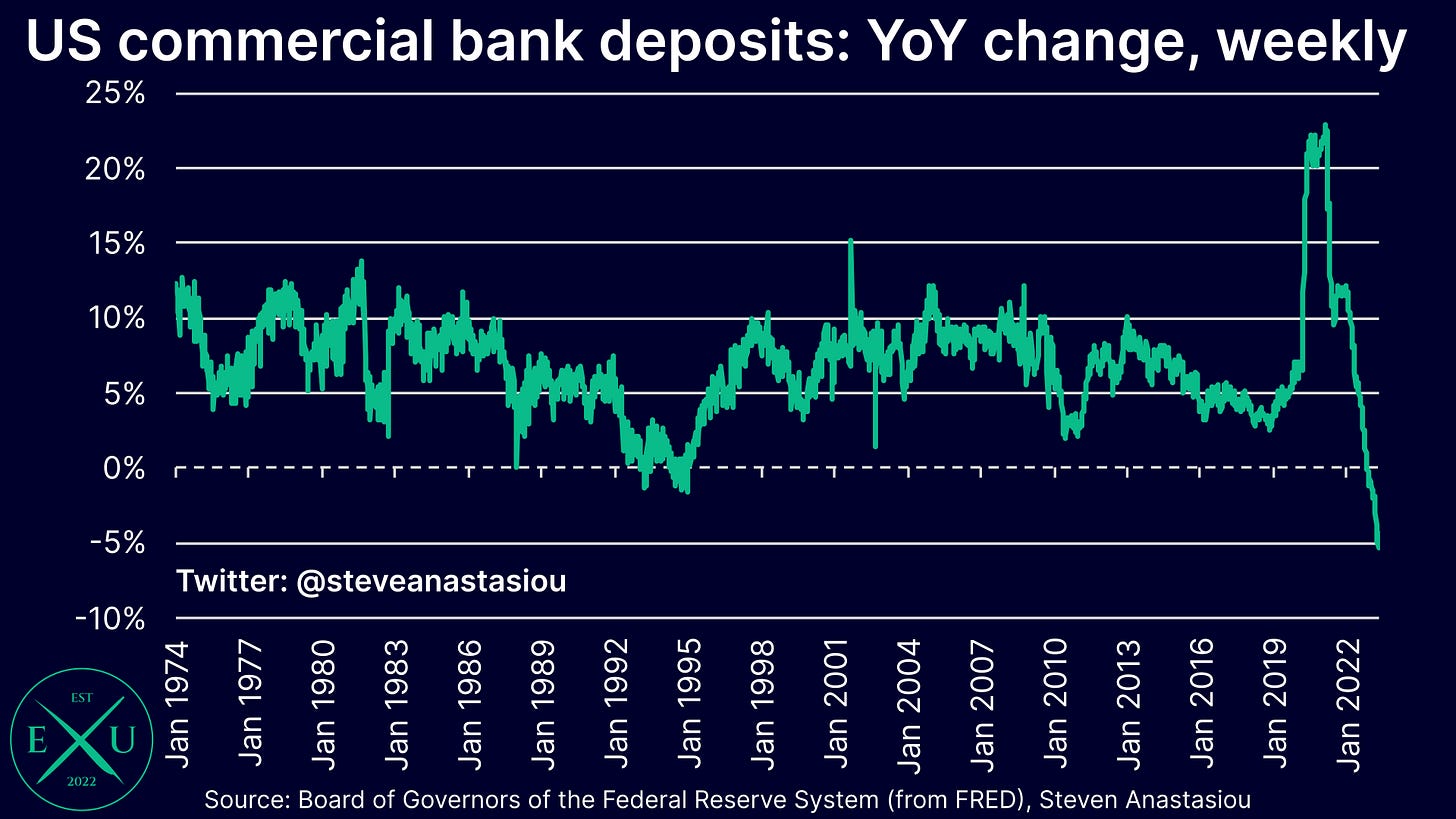

Furthermore, while raising deposit rates can encourage deposits to remain/shift to a given bank, there will continue to be downward pressure on deposits across the banking system as a whole, for as long as the Fed continues its QT program.

Worsening liquidity & an erosion of profitability risks a major lending slowdown, hitting economic growth and creating further problems for banks

Worsening liquidity and an erosion of profitability also risks a sharp tightening of lending standards and a significant moderation (or outright contraction) in bank lending.

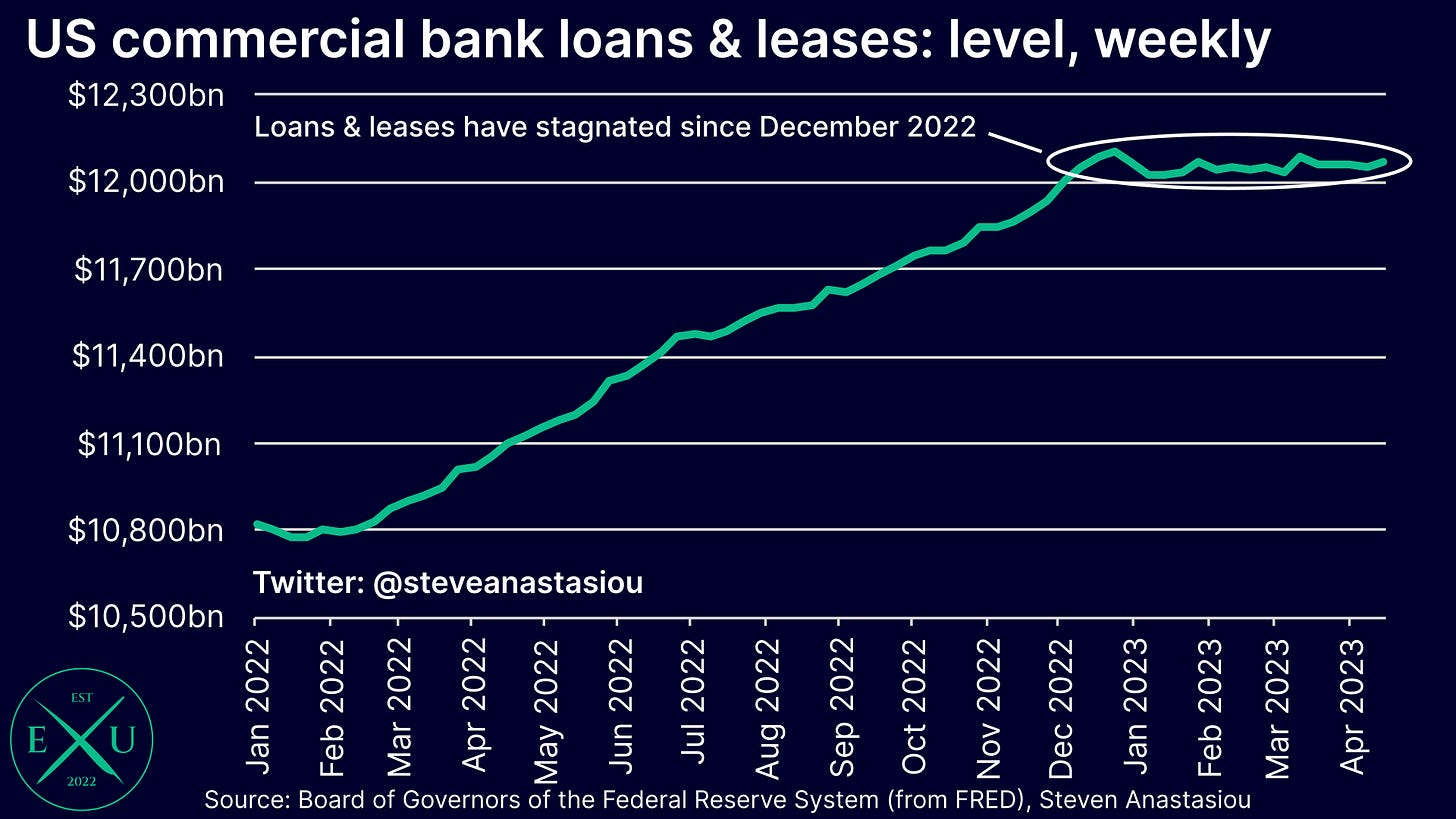

Given that the Fed’s aggressive rate hikes have been occurring for some time now, we can see that this has already been happening, with bank lending stagnating since December 2022.

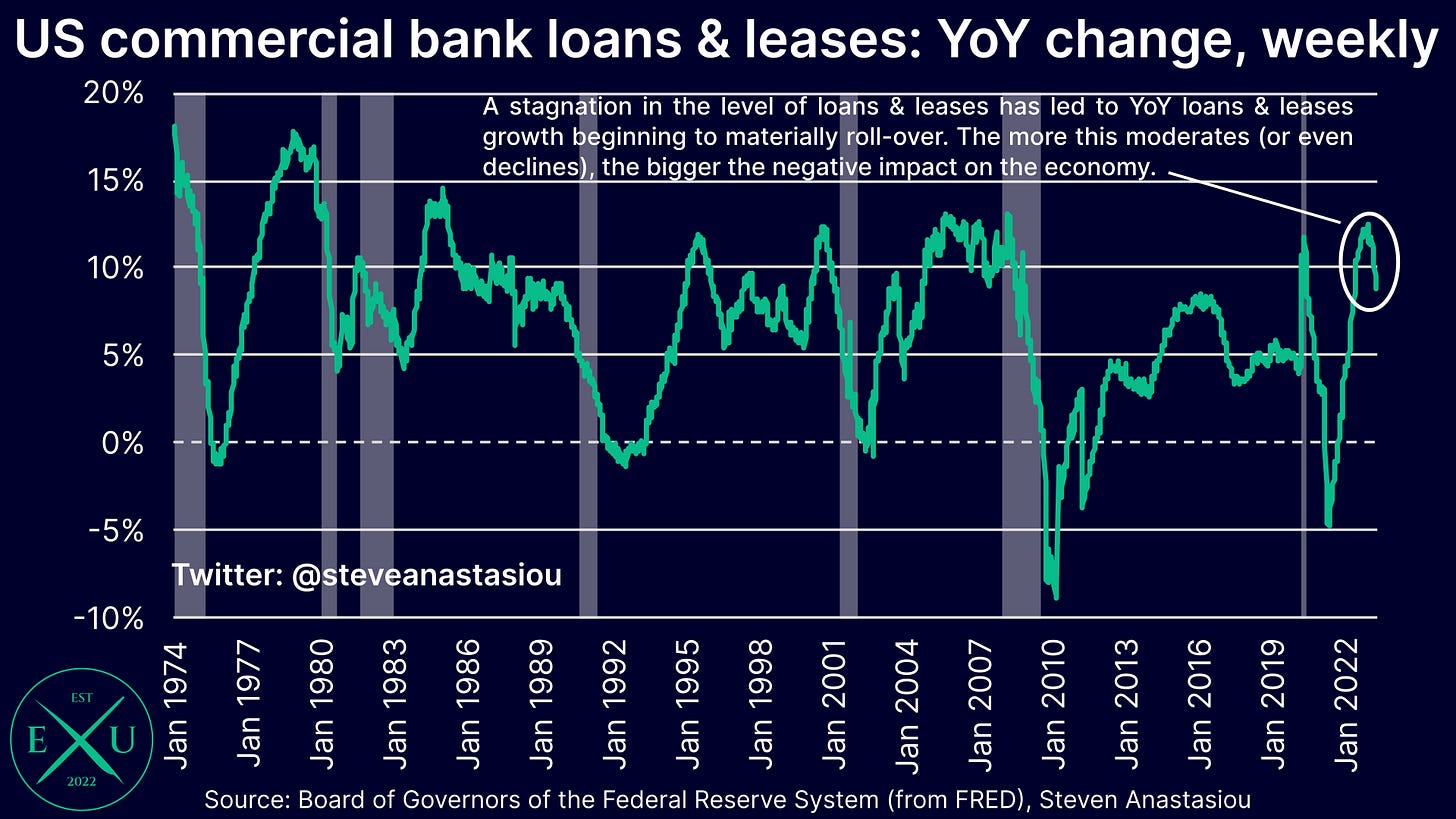

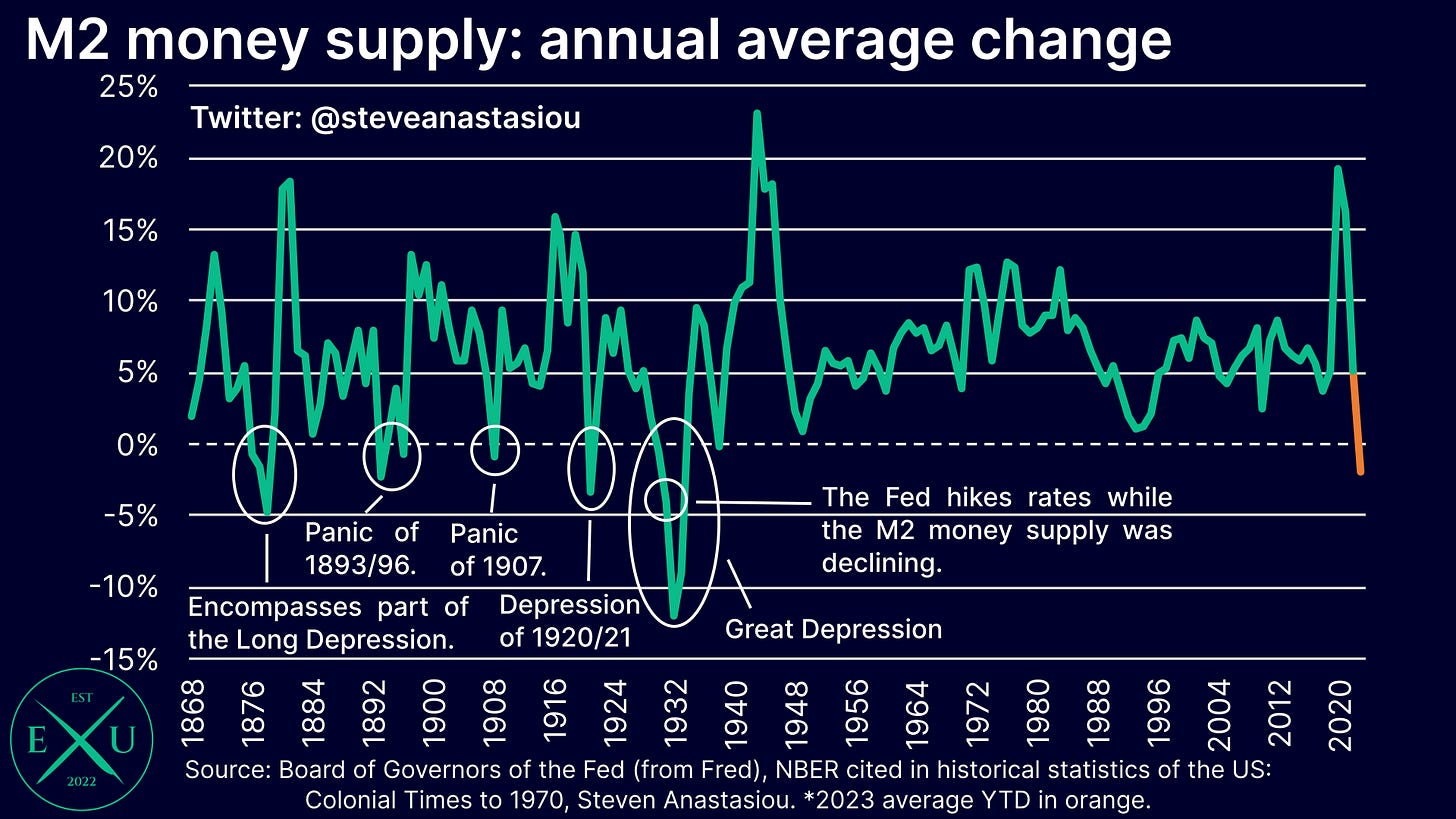

While the YoY lending growth rate had been buoyant, the stagnation in loans & leases has resulted in YoY growth materially rolling over. From a peak of 12.2% in December, growth has moderated to 8.8% as of 19 April. With loans & leases showing no signs of moving higher and the Fed’s aggressive tightening continuing, the YoY growth rate appears set to continue moderating over the weeks and months ahead, which will put further pressure on M2.

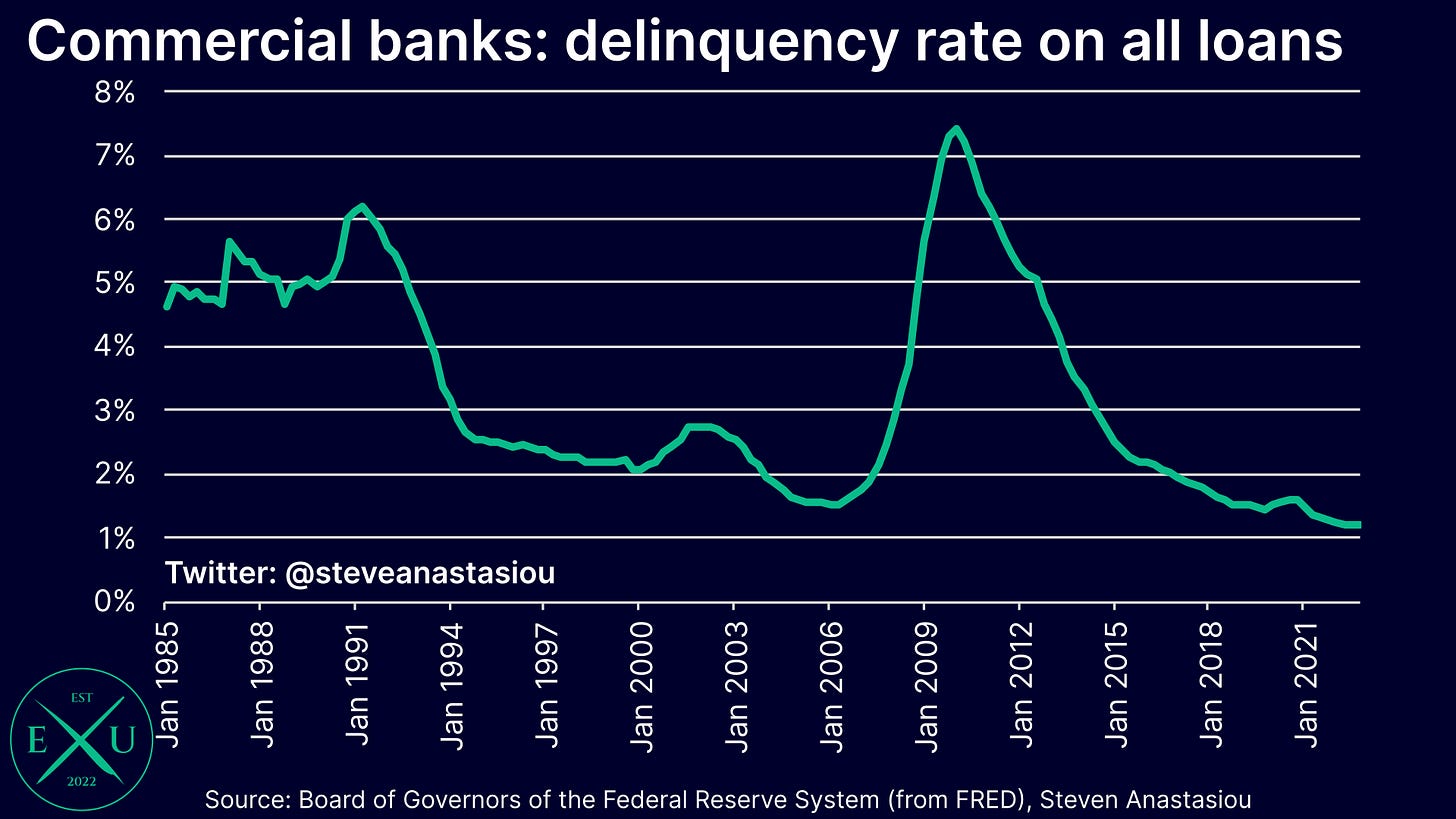

The potential for this to materially hit nominal economic growth could result in significantly increased bank stress. For up until now, delinquencies have remained at relatively low levels. A major deterioration in the economy would be likely to significantly change that. This would mean that banks will not only have to deal with liquidity stress, but rising credit losses.

This adds to the risk of creating a vicious cycle of further bank failures, which leads to a further tightening of lending standards and a further reduction in lending. This then leads to further downward pressure on the M2 money supply, negatively impacting nominal economic growth and raising the odds of deflation (which makes debt servicing more difficult). This would lead to further bank credit losses, and so on.

History has provided many examples of the dangers that arise when deposits & the M2 money supply fall — the Fed needs to recognise the warning signs before a deflationary bust arises

High inflation should no longer be the key concern — with the M2 money supply falling, so too will inflation over time.

Instead, a decline in bank deposits and the M2 money supply, means that the bigger concern should be the risk of a deflationary bust, as aggressive Fed tightening and falling deposits create a host of issues for the banking system.

Whether it’s the Long Depression (1873-79), the Panic of 1893/1896/1907, the Depression of 1920-21 or the Great Depression, it thus shouldn’t come as a surprise that falling M2 is historically associated with economic depressions and panics — just as more debt and leverage artificially fuel economic growth, declines in the M2 money supply instead encourage a deflationary bust.

Instead of focusing on lagging indicators like services prices and employment, the Fed needs to recognise the importance of the money supply, and loosen the aggressive tightening that it has employed.

Continuing to maintain its current level of tightening, which is leading to declines in bank deposits and the M2 money supply, risks further bank failures and a deflationary economic bust.

Thank you for reading!

I hope you enjoyed my latest research piece. In order to help support my independent economics research, please like and share this post.

If you haven’t already subscribed to Economics Uncovered, subscribe below so that you don’t miss an update.